|

| A constant, revolving mess. |

| Wrapped in plastic, hoping for the best. |

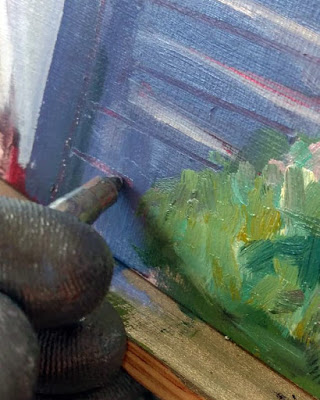

| If you paint out of a moving car, as I did here, you have to wait to clean your brushes. |

|

| Soaking them in coconut oil can sometimes loosen up dried paint. |

Watch Me Paint: World-Class Art, World-Class Instruction

|

| A constant, revolving mess. |

| Wrapped in plastic, hoping for the best. |

| If you paint out of a moving car, as I did here, you have to wait to clean your brushes. |

|

| Soaking them in coconut oil can sometimes loosen up dried paint. |

|

Sea Fog on Main Street, by Carol L. Douglas. When painting plein air, you don’t have time to wait for the painting to dry to draw lines.

|

I’m working on a commission that has a lot of architectural detail. I don’t want the end result to be fussy. I’m not a clean renderer like Frank Costantino. He can drop a fine line with a rigger and it falls into the painting, cool and elegant.

|

| Working backwards allows you to make clean edges without being overly fussy. |

|

| Start by getting rid of excess paint. |

|

| The line going on with a bright. |

|

| It’s easier to paint a line with a flat on its side than with a small round. |

|

| Then push the background color right up against the line. |

|

| After two flags, a chair, and a lot of white trim, I was so cramped up by precision that I had to do this fast surf exercise to wash out my mind (and loosen up my hand). |

| Take a boat. They’re objectively safer. Tricky Mary in a pea-soup fog, by Carol L. Douglas, courtesy Camden Falls Gallery. |

According to the people who measure these things, the most dangerous form of transportation is your family car. There are two seasons when highway accidents jump—summertime and the holidays. Surprisingly, Massholes and New Yorkers are better drivers than Mainers.

|

| The empty road, in Yukon Territory or eastern Alaska. The risk changes from distracted drivers to enormous animals. |

|

| Life in the breakdown lane. |

| The more vertical the brush, the more flow. |

Watercolor brushes are softer than oil-painting brushes. The most expensive are sable brushes, and unlike oil-painting brushes, the difference is worth paying for. Natural bristles combine strength with suppleness and hold more paint than synthetics. However, there are some fine synthetic brushes out there. Several of my go-to brushes are Princeton Neptunes.

|

| Made with the synthetic spalter brush, above. |

Except for squirrel mops, watercolor brushes drop more pigment the more vertically they’re held. You can use this to move from a filled area to a broken one in one brush stroke. In all the following examples except for the mop, I’ve held the brush both ways. A good general rule is to carry the vertical brush slowly and in a controlled manner; pull a horizontal brush more rapidly to get the least amount of paint contact with the paper.

The brush I used for the photo montage above is a 2″ flat synthetic mottler or spalter brush. I like this shape for both oils and watercolor. It’s a relatively inexpensive brush that gives a beautiful wash. It’s useful for covering large areas quickly, but with precise edges.

| A flat gives you a good even wash. Used on its side, it can give you a controlled line. |

|

| And that would be the bright. More punch, less pigment. |

|

| You can’t do either of these things in any other medium. |

Because of the way watercolor bleeds, its brushes can be used in ways not possible in any other medium–a long blend of different pigments, or by painting a shape in clear water and then dropping pigment into it.

| Round brushes are just more lyrical than flats. |

| A mop brush makes a perfect wash, but it does so much more as well. |

Squirrel mops are the most uniform wash brush you can use. It’s virtually impossible to make them skip, so use them where a lovely flat wash is a goal.

| Mop brush on very textured paper. |

|

| One of my favorite tools, a natural sponge. |

Natural sea sponges are multi-purpose painting brushes. Use them to apply or remove paint. They can be as subtle or bold as you wish.

|

| Paint lifted (left) and applied (right) with a sponge. |

Your brushwork contributes immeasurably to the quality of your painting. Don’t dab or be diffident; plan your strategy and then execute it with boldness. To do this, of course, you have to practice.

The best way to learn about your brushes is to experiment, but meanwhile, here’s a handy guide to oil painting brushes.

Above is a sable flat brush by Rosemary & Company. It can put down a very smooth surface and offers a lot of control, but it doesn’t carry the quantity of paint that an equivalent bristle brush will. I do have many sable brushes, but I save them for thin work in the studio.

This is a Robert Simmons Signet flat brush. The paint it lays down is both rougher and more impasto than the sable.

Flat brushes make an immediate, energetic mark. They’re excellent for fast, powerful surface work, long sweeping strokes, and blocking in shapes.

Used on their sides, they also make great lines, far more evenly than a small round can do.

Two rounds of very different sizes. A round is a more lyrical brush than a flat, and is a classic tool for painterly surface marks. It can be used to make lines that vary from thin to thick. A pointed round is used for fine detail. Bristle rounds tend to lose their points very quickly, however.

A bright is a less-flexible version of a flat. It’s great for short, powerful strokes or situations where you want a lot of control.

A fan brush probably has no place in a plein air kit, but I carry one anyway. I use it for blending, as on the left, although some people like using it to make whacked out marks as on the right. The problem is, it can carry very little paint, so its marks tend to be either gooey, as above, or very abrupt.

In my studio, I just use a clapped out soft-haired brush to blend.

|

|

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, 1565, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, image courtesy of the Courtauld Institute of Art but the painting has been stolen.

|

Yesterday was the kind of day that drives poets mad. Just below freezing, it rained heavily, with gusts of wind. Our plein air painting class was forced into the studio.

|

| Abstract design by Christine Covert |

Painting runs along two parallel tracks. The first is design. This is why painting teachers relentlessly push students to do thumbnails and other value sketches. Value is our most important tool. Get it right, and you can be wrong about a lot of other things.

|

| Grisaille by Jennifer Johnson. |

| Grisaille by David Blanchard. |

| Grisaille by Chris Covert. |

|

| The Farm at Olana, by Carol L. Douglas |

| Mamaroneck River, by Carol L. Douglas, in its finished form right before it went on the auction block. |

| Mamaroneck River, when the second layer was done but the top layer hadn’t been started. |

|

| Grain elevators, Buffalo, by Carol L. Douglas is an example of a cold-wax medium painting. It gives tremendous latitude in effects. |

| The drawing layer is always done with solvent, whether in the studio or in the field. That’s Sandy Quang, back when she was my studio assistant. |

| Clip this and paste it in your pochade box until it’s a habit. |

|

|

The Artist’s Studio in an Afternoon Fog, 1894, Winslow Homer. Courtesy of Memorial Art Gallery.

|

|

| The basic structure of The Artist’s Studio in an Afternoon Fog, above. Use tracing paper to do this step. |

| Experiment with different values within the painting’s structure. |

|

|

Sunlight on the Coast, 1890, Winslow Homer. Courtesy Toledo Museum of Art.

|

|

|

The Fox Hunt, 1893, Winslow Homer. Courtesy Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

|

A painted value study is a great tool for understanding your subject.

|

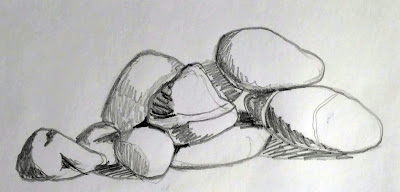

| Pile of rocks value study, by Jennifer Johnson |

Last week, I had you find and identify the simple shapes within a drawing. The prior week, we learned how to do abstracted value studies of our own homes. This week I want you to do a monochrome (black and white) painting based on a value drawing.

| Jennifer started by doing this meticulous, detailed drawing of her pile of stones. |

| She traced the basic shapes for each iteration. It saved her tons of time and made it easier to do multiple iterations of the same idea. |

|

| Next came a simple value sketch of the rocks. |

|

|

Winch (American Eagle), by Carol L. Douglas, courtesy of Camden Falls Gallery.

|

|

| That painting is just a series of simple shapes. |

|

| Old Greek Revival farmhouse in Western New York. |

|

| This is a computer estimation of what it looks like to me without my glasses. |

|

| Either way, it breaks down to these approximate shapes. Anyone can draw them! |

| My house drawing from last week. |

|

| Does it reduce to a few simple shapes that make a pleasing pattern? I think so. |