For some artists, the hardest thing in painting isn’t drawing or color-mixing but how to price their work. Charge by the square inch, of course.

|

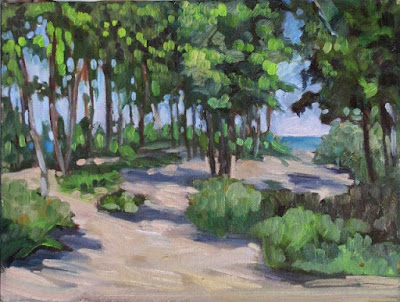

| Keuka Lake Vineyard, 30X40 by Carol L. Douglas, is available through Kelpie Gallery |

A proper price is the meeting point between how much you can produce of the product and how much demand there is for it. If you can’t keep your paintings stocked, you’re charging too little. If your studio is full of unsold work, you’re either charging too much or not putting enough effort into marketing. Your job is to find that sweet spot.

Art sales are regional. If you live in a community with an aging population and a prestigious art school, you’re going to have low demand and high supply. If you live in a booming new city, you will have more demand and prices will be higher.

Art is not strictly a commodity, however. A painting’s value depends on the artist’s prominence. Most artists are terrible judges of their own work, seesawing between believing they’re geniuses and thinking they’re hopeless. Such subjective judgments hinder their ability to price their work.

|

| Art festivals are a good way to establish a price history. I don’t miss them, however. |

Don’t assume that because you labored for a long time over a piece, it is more valuable. Your challenges are not the buyers’ problem.

You can simplify the problem by setting aside your emotions and basing your selling price on the size of the piece and your selling history. How do you do that if you’ve never sold anything before? Survey other artists with the same level of experience and set your first prices in line with theirs. Visit galleries,

plein air events and art fairs. If you see a person whose work seems similar to yours, find his resume online and check his experience. Know enough to be able to rank events. Painting in

Plein Air Easton is not the same as painting your local

Paint the Town.

Charitable auctions are a good way to leverage your talent to help others. They provide a sales history to new artists. (But they aren’t tax deductible contributions.)

Let’s say you gave an 8X10 watercolor of the Old Red Mill to your local historical society, which turned around and sold it for $100. Great! You have a sales history (albeit a limited and imperfect one) from which to calculate prices. Just figure out the value per square inch and calculate from there.

Square inch is the height times the width. That means your 8X10 painting is 80 square inches. Dividing the $100 selling price by 80 gives you a value of $1.25/square inch.

To use this to calculate other sizes, you would end up with:

6X8 is 48 square inches. 48 X $1.25 = $60

9X12: $135

11X14: $240

12X16: $315

In practice, my price/sq. inch gets lower the larger I go. This reflects my working and marketing costs, some of which are fixed. If you started with my example, above, a 3X4” painting would more reasonably sell for $3 a square inch or $36, and a 48X48” painting for $.75 a square inch, or $1700. But that sweet spot between 6X8 and 16X20 are a fixed cost/inch, rounded off for convenience.

|

| My price list is on Google Drive and I can access it wherever there’s phone service. |

Charity sales are known for seriously underpricing work, but it’s better to start low and work your way higher. Periodically review your prices, and make sure you have a copy with you at all times, because people will ask you about paintings at the strangest times. I keep mine on a Google sheet I can refer to from computer or phone.

Once you have a price guide, it should be absolute. I adjust it slightly for family members (or more likely just give them the painting), but I use the same price structure in events and galleries.

You should continuously update your prices based on your average sale prices for the prior year or two. The goal of every artist ought to be to sell at constantly rising prices. When you find yourself “painting on a treadmill” to have enough work for your next show, it’s definitely time to charge more. Each time you show, your work will be better known, and over time your prices will rise.

The marketplace favors fair, consistent pricing. I charge the same amount everywhere I sell. I don’t want to undercut my galleries.

And I don’t explain my prices, for the most part. Does anyone ever tell Christian Louboutin that $995 is a bit much for a pair of platform suede pumps? No; they either understand Louboutin’s market or they don’t buy designer shoes.

This post originally appeared on December 18, 2017. How quickly a vacation rolls past! Have a happy New Year, and I’ll see you again on Wednesday.