Risk-taking is not only good for art, it’s good practice for life.

|

| Midsummer, by Carol L. Douglas. Oil on canvas, 24×36. |

“I can’t remember what you told me you plan to concentrate on during this residency,” Bobbi Heath said.

That was because I had deftly avoided answering her question. A residency is a great time to set up a challenge and then answer it. The people vetting your application want to know how the opportunity is going to expand your vision or change your practice. We try to do something inventive yet considered. Of course, that sometimes means you’ve painted yourself into a corner before you’ve even started.

I’ve been thinking recently about architecture, and what gives us a sense of place, and, of course, boats. I’m sure I could have whipped up a grandiose statement with those ingredients, but my heart wasn’t in it.

|

| Farm, by Carol L. Douglas |

Nova Scotia has a vernacular building style that’s peculiar to Canada and Britain. These are steep-roofed houses with twin gables. Sometimes they have matching window bays. They may be tarted up with gingerbread, or they may be very simple. They’re always proper, like a nice old lady in her best pantsuit. It’s not a common building style in most of the United States, but there are many examples in my part of Maine.

It was thinking about them that made me spend my first several days painting buildings from above. There is, in fact, something audacious about this kind of painting: it’s based on drawing.

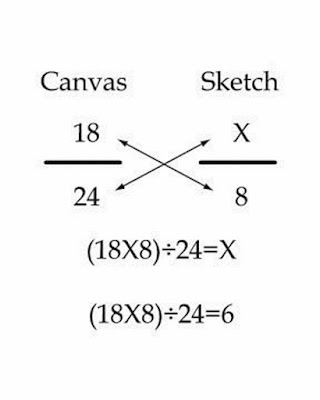

“You must have taken mechanical drawing or drafting in school,” an artist said after she saw my sketch for Midsummer. Rather, I learned to draw when perspective and measurement were routine. If I could get students to do one thing, it would be to spend twice as much time drawing as they ever spend painting. But I digress.

As fun as painting houses has been, they’re still well within my skill set. It was time to radically mix it up.

|

| Her laundry and lupines, by Carol L. Douglas |

I offered to demo in downtown Parrsboro. I painted the estuary two weeks ago and wasn’t keen on doing it again so soon. My other options were commercial buildings. Behind one was a laundry line. It was unfortunately surrounded by a scramble of wild roses and lupines. My least-favorite things to paint are flowers.

I drew the scene three times and realized I was getting nowhere with the scientific method. I started lashing paint on without a good underpainting, moving objects in mid-process, and doing all the things I tell students to never do. It took much longer than a well-drafted painting ever does.

Is it successful? It doesn’t really matter. It was a good way to force myself past my resistance to flowers, and to hang my painting on a tale. The laundry told a powerful story to me. It was a single woman’s working wardrobe, hanging outside a simple, concrete-block apartment. Everyone paints white sheets. I painted black leggings.

When I was done, I wanted to paint the exact same subject again, but this time I would approach it very differently. The beauty of a residency is that I can do that.

Why push yourself out of your comfort zone? It develops your tolerance for change. Human beings are wired to experience negative results more keenly than positive ones. It’s called our

negativity bias, and it’s there to stop us from doing stupid things that will kill us.

This bias carries over to predicting outcomes. We tend to think things will go wrong more than they’ll go right. The fewer risks we take, the stronger that belief is. We can become immobilized by the fear of change.

There are a few ways around this, of course. Personally, I believe that an interactive God has my back. You can call that a positivity bias, if you want.

Repeatedly taking controlled risks is in itself therapeutic. It reduces our negativity bias. Our brains learn that risky ventures can succeed, and that failing is not necessarily awful.

That is not only good for art, it’s good practice for life. This week, challenge yourself.