Failed paintings are less common than you think. You just have to look at them the right way.

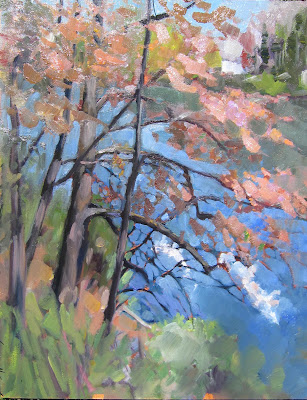

| This is an example of an unfinished painting that pointed the way forward. It took years for me to understand where I was going with it. |

Last week, as I dithered about which paintings to submit to Santa Fe Plein Air Fiesta, a reader wrote, “Can you write a post sometime about what you do with the second-tier paintings you make? Do you just scrape them? Give away to unsuspecting strangers? Donate, unsigned, to charity thrift shops? Let them accumulate and breed in a dark basement?”

First of all, let me be clear that I don’t think any of last week’s five (or the one I didn’t finish on Friday) are ‘second tier’ paintings. I’m happy with them all, and I think they’re sellable. They’re not sellable in either of the galleries that represent me on the Maine coast, however. I have two options: I will market them through my own studio, or sell them online through Chrissy Pahucki’s pleinair.store.

|

| Spring, by Carol L. Douglas. I hated this when I painted it. Now I’ve almost caught up with it. |

I’ve done plein airevents where I’ve sold exactly nothing, and other events where I’ve sold everything. It’s unpredictable. At the end of the summer, I usually have more work left over than I’ve sold. Usually these works end up selling in future years. Occasionally, they end up donated to fundraisers, but only for organizations I care about, who can get a fair-market price for their work.

But let’s talk about paintings that aren’t good enough to sell. It happens, although the artist in his or her post-creative exhaustion is the usually the last person to be a good judge of whether a painting has merit or not. Some artists are quick to scrape out everything they don’t like. After all, professional-grade painting panels are expensive.

|

| Hollyhocks, by Carol L. Douglas. Sometimes you have to paint something a number of times to realize you aren’t interested in the subject. I thought I should be, since I’d planted this garden. |

I don’t think scraping out is a good idea. It means new and difficult ideas are stillborn. How do you find a path forward without contemplating each tangled byway to see if this is the way forward?

These paintings—the edgy, difficult ones that don’t seem to have much value—go on racks to dry, and then into into bins in my studio, where they’re available at a reduced price. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve looked through those bins and suddenly seen something wonderful that I’ve never noticed before. My brain likes the status quo. Often it takes a few years for it to catch up with the intelligence of my hands. Those bins are part of the process of dragging it forward.

| 59th Street Bridge Approach, by Carol L. Douglas. There are subjects I used to love, but love no more. |

I have a few customers who love the bins, and they root through them every time they visit. They can definitely get a good bargain there, because the binned paintings are available for a fraction of the cost of framed paintings.

Sometimes, these binned paintings live on as reference for larger works—I’d much rather scale up a field sketch in the studio than a photograph. Sometimes, I revise and finish in the studio. For example, the seasonal lag between New Mexico and Rockport, ME, means that I can comfortably find an apple tree here to use to finish Friday’s painting.

But, yes, sometimes I paint total dogs that aren’t useful for reference, for overpainting, or for any purpose known to mankind. These I destroy. Although that doesn’t happen very often, I reserve the right to edit my own legacy.