Before you can paint successfully, you have to learn to draw.

|

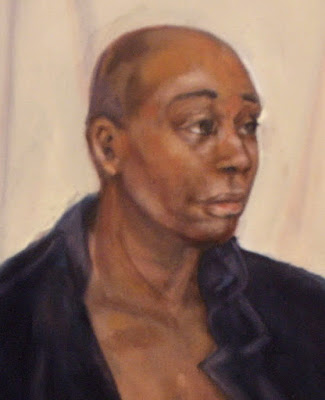

| I love drawing in church, especially when there are sleepy teenagers. This drawing started with simple analysis of shape. |

One of the problems with writing about ‘how to do art’ is that you’re speaking to all levels of experience. Today we’re going right to the beginning of measurement. Almost everyone can get the details of a drawing right. Where they go wrong is with overall proportion. Drawing is, first and foremost, a technical exercise in seeing size relationships. Get that right, and the details hardly matter.

|

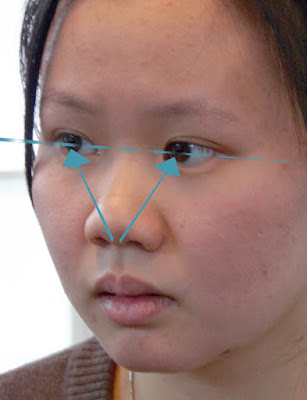

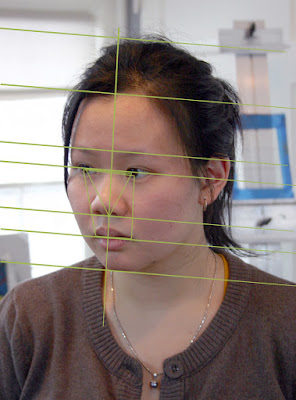

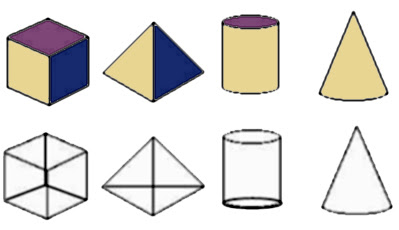

| All objects can be broken down into simple shapes and angles. |

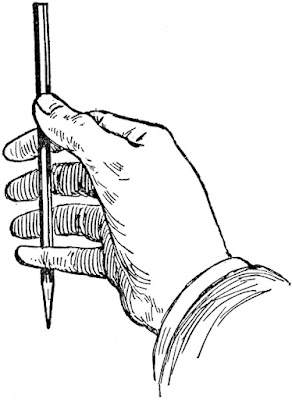

You’ve all seen artists holding a pencil up to an object. What they’re doing is rough measuring. It’s simple to do, but tough to photograph. Hold your pencil up like a ruler in front of the object you’re drawing. Move it around to see the relative height and width of the thing. For example, the toy truck below is about 1.5 times as wide as it is tall. Figure that out by holding your pencil first along the vertical access, then along the horizontal access, and comparing where the lengths stop along the pencil.

|

| It’s not just an affectation; it’s really how artists measure. |

A common beginner error is thinking that you have to transcribe the lengths exactly to the paper. The drawing can be any size you want. Start by figuring out how big you want the object to be on your paper, and make two hash marks to represent that. Then, if your object is half as wide as it is tall, figure out that relationship and mark it too.

|

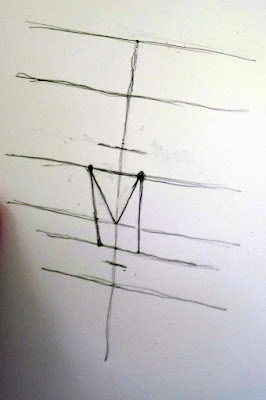

| Start by measuring out the simple shapes and angles. |

You can also use your pencil to figure out the other important thing in drawing: the angles of lines. Formal perspective is important, but not as important as learning to see angles. If you develop the ability to see angles, you’ll have better natural perspective than if you try to fit up what you see to a theory.

|

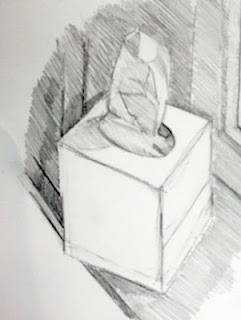

| Next, rough in the values. That means the lights and darks. |

Do your measuring with one eye closed, especially if you’re working in a tight space. Art books will tell you to measure with your arm straight out. That’s not always practical. Instead, try to have the pencil the same distance away from your eye each time you take a measurement. I do that by noting how my arm is cocked.

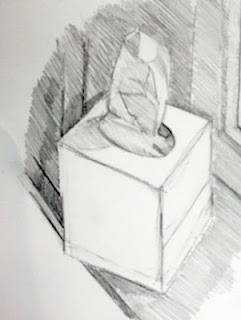

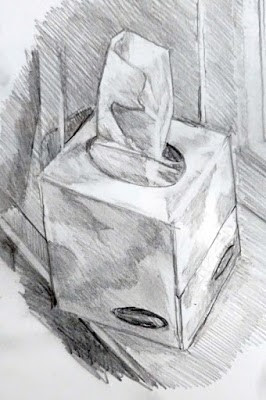

Today’s exercise is based on a tissue box I drew in church. It had lovely angles. However, what you see in the photo isn’t what I saw while working. A drawing from life will never match what the camera records. Cameras lie just as much as artists do.

|

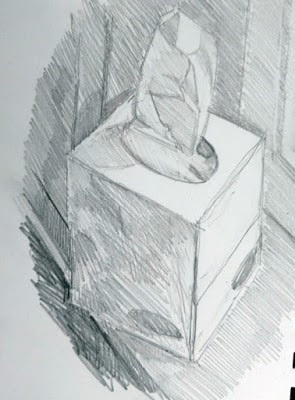

| Begin to refine and strengthen the light and dark shapes. |

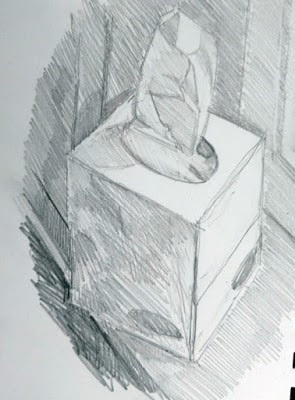

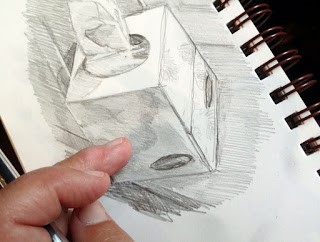

All drawing starts with simple shapes. After laying them down, I check and correct them. I do this by analyzing each large shape. Where does the back of the box intersect the tissue column? Is the curve of the cutout fat enough? I discovered that my cube wasn’t really tall enough, so I added some to the bottom.

The next step is to establish some overall values. “Value” just means how light or dark something is. This box was sitting on a south-facing windowsill behind a person who was casting another shadow. Thus, the window-frame behind the box was in deep shadow, but not nearly as dark as the photograph. I roughed in those darks first. They helped me know how to shade the box properly.

|

| If you’re using graphite or charcoal, you can blend with your finger. Otherwise, use a stump, a tortillon, or a bit of rag. |

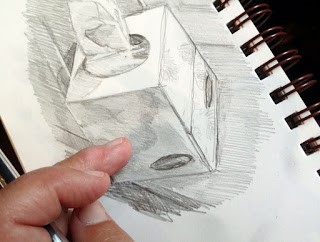

Next, I set shadows on the tissue box itself. I am more concerned with the column of tissue, so with each pass, I spend more time on that.

Finally, I did some blending, using the handiest tool I carry: my finger. You should use a

stump or

tortillon on work you care about, but in a pinch, your finger works great. But don’t blend pigments other than graphite or charcoal with your finger; they may contain toxic metals.

|

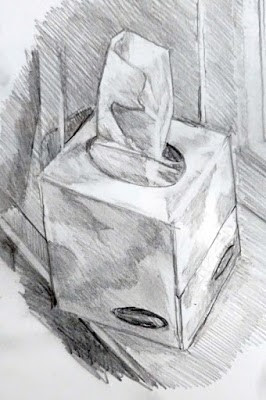

| Voila! I have a tissue box drawn and my pastor is just winding down his peroration. |

Note that I never bother much about my mark-making. It can take care of itself. I’m mostly interested in applying accurate values. I did this drawing with a mechanical pencil, which will never be as luscious as a good graphite stick, but it survives banging around in my purse week after week.

Some general rules:

- Draw everyday objects. The better you get with these, the better you’ll be with complex subjects. There’s amazing beauty in everyday things.

- Draw any time you get the chance. I did this drawing in church, and I didn’t miss a word. Drawing and language don’t use the same channels of your brain.

- Measuring is the most important part of drawing. Keep checking and correcting sizes.

- Start with big shapes and break them down into little shapes. If the big shapes are right, the smaller parts will slip into their spots just fine.

- Value is relative. How dark something is, is only important in terms of how dark its neighbor is.

- Constantly recheck shapes and values as you go.