The greatest obstacle to painting nocturnes is convincing yourself that you want to go back out after supper.

|

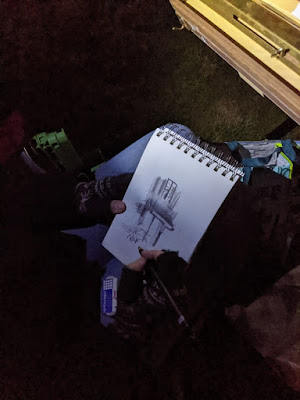

| Linda DeLorey painting a nocturne at Rockefeller Hall. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Johnson) |

I’ve been teaching at Schoodic Institute for a long time. Every year, I check the moonrise schedule and determine whether we’ll get a full moon for a nocturne. It seldom seems to work. The last time our schedule aligned, the moonrise over Arey Cove was brilliant, but the mosquitoes were ferocious. We were driven off long before our canvases were covered.

(Before I taught Sea & Sky at Schoodic, I taught it in Rockland and then Belfast. This is before we all had cell phones with flashlights. One year, Sandy Quang got lost and fell over a bluff. Luckily there was beach below.)

|

| A late-night critique session with Rebecca Bense and Jennifer Johnson. |

We’ve always done this workshop in August, when the days are long. This year, it’s in October, because Maine’s COVID-19 regulations made it impossible for out-of-staters to come in without quarantine in August. That means it’s dark by 6:30. Walking back from the Commons in the dark, we realized that Rockefeller Hall would make for smashing nocturnes, with or without moonlight. It’s a very safe location, since the offices are closed at night.

The greatest obstacle to painting nocturnes is convincing yourself that you want to go back out after supper. It sounds like a brilliant plan at breakfast. After you’ve already painted for eight hours, and maybe had a glass of wine, the idea of dragging your stuff back out in the dark sounds awful. Of course, there are more opportunities for mishaps. Brushes drop into the grass and roll silently away. Nocturnes are unfair to watercolorists, who fight the night mist that keeps their paper saturated.

|

| My students are used to starting with value studies, so painting at night isn’t such a shock to them. |

For me, it’s easier to get up at 2 AM and paint. Even so, you then have the challenge of leaving your warm bed at an unnatural hour. Either way, if you persist through your own resistance, you’re in for a treat. The air is fresh and cool; the commonplace becomes beautiful and mysterious.

I’ve given up using a headlamp for nocturnes; I find they blind me as they flicker back and forth. Instead, I brought enough rechargeable book lights to share with my students. My students have been endlessly schooled in value studies, so they took to the limited color range of nocturne paintings immediately. In general, there’s no color in the night sky except inky blackness and the color of any lights. Under a door lamp or inside a window, you will sometimes see a short burst of color, but it’s passing and brief.

|

| Most of my intrepid band of painters, less Jennifer Johnson, who took the photo. That’s Beth Car, me, Jean Cole, Ann Clowe, Rebecca Bense, Carrie O’Brien, and Linda DeLorey. |

“Prepare for the worst and hope for the best,” my monitor Jennifer Johnson says. This year all my students are from the northeast, so they know what extensive array of clothing is suitable to October. It can be sunny and beautiful one day and sleeting (or worse) the next. I’m, as usual, far less judicious, since I don’t really believe in winter. I capitulated to the point where I brought long pants, but I haven’t needed them. I’m still in capris, sandals and a linen painting smock.

|

| Me, demoing. (Photo courtesy of Ann Clowe) |

October is always the most beautiful month in the northeast and the weather has been fine. It’s foggy in the morning, because the sea is warmer than the air. “I’d love a demonstration on painting fog,” Ann Clowe told me. I love painting fog, so I enthusiastically set up to comply. Unfortunately, the fog burned off too soon, and we had another pristine autumn morning, surrounded by the myriad colors of Autumn on every side. It’s cooler here than it is in August, but most importantly, the ever-present madding crowds are mostly absent.

I’m teaching my annual Sea & Sky workshop in Acadia National Park this week. After that, there’s Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air in Tallahassee, Florida, in early November, and a few more plein air classes in Rockport, ME. From there on in, it’s all Zoom, Zoom, Zoom until the snow stops flying.