The important thing you bring to class is not your prior painting experience, but your attitude.

To teach painting effectively, one must not only know how to paint, but be able to break that down into discrete steps and effectively communicate those steps to students. That’s straightforward, right?

What isn’t so straightforward is how one prepares to be a good student. Learning is a partnership, and students always bring attitudes, personality and preconceptions to the mix. Unless a class is marketed as a masterclass, you don’t need to worry overmuch about your incoming skill level. However, some rudimentary drawing experience will make you a stronger painter.

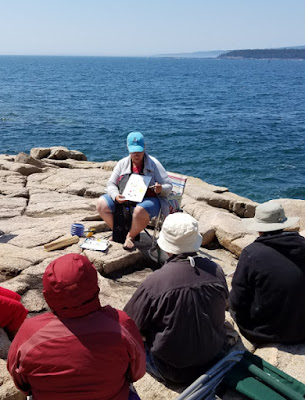

|

| Photo courtesy of Jennifer Johnson. |

More important is intellectual openness. This means the ability to receive correction and instruction without being defensive. (I’ll freely admit I came late to this myself.) The greatest teacher in the world is useless if you’re not prepared to hear what he or she has to say.

Nobody ever paints well when they’re integrating new ideas; it’s far easier to stick with the same old processes even when they don’t work particularly well. They’re familiar. Students should come to class expecting to fail, and even to fail spectacularly. “When I take a class, I produce some of the worst crap in the world, but I will have experimented,” one artist told me. The people who produce pretty things in class are often playing it safe. They’re scared of pushing themselves past what’s comfortable.

Are you worried that you’ll lose your style if you do it the teacher’s way? Your inner self will always bounce back, but hopefully you’ll have learned something that enhances that.

What we teach is a process. The primary goal is to master that process, not to produce beautiful art in any style. If that happens, it’s a bonus, but the real takeaway ought to be a roadmap you can follow long after your teacher is gone.

|

| Photo courtesy of Jennifer Johnson. |

The student has some basic responsibilities to his fellow students. He should be on time and bring the proper equipment and supplies. Furthermore, he should be polite, friendly, and supportive to his fellow students. The importance of this latter cannot be overstressed. An overly-needy or unfriendly student can ruin a workshop for everyone, as there’s no getting away from him.

I’ve written before about the pernicious practice of negative feedback, but it’s pervasive in our teaching culture. It takes a while for students to get the hang of recognizing their successes. Before we talk about what needs fixing, we need to trust each other. One way we learn distrust is the idea that, in a critique, we are required to say something unfavorable. Only talk about what’s broken if, in fact, it’s actually broken.

|

| Photo courtesy of Ellen Trayer. |

It helps progress to be optimistic, excited and motivated. I’m blessed with an unusually great class this session, and one of the things that distinguishes them is that everyone really wants to excel in painting. They all have a strong work ethic.

Lastly, I think a good student brings a measure of self-advocacy to class. I’m listening hard, and I’m watching carefully, and I still sometimes miss things. I like it when people bring problems or concerns to my attention. It makes me a better teacher.