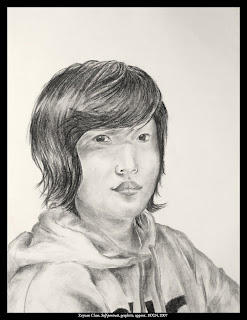

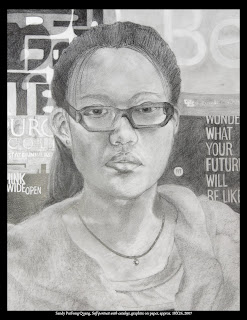

|

| As-yet-untitled landscape of New Mexico by Cindy Zaglin, acrylic on canvas. Light, bright, abstract, and ultimately it looks like the place felt. |

The working art world—as much as any clique—tends to be insular. Art markets are provincial communities that are inclined to distrust outsiders or new impulses. To really break out of the corner into which one has painted oneself, to violate the community’s intellectual, technical or social standards, can be tremendously difficult.

Because paintings are tangible objects, the culture of painting is less subject to mass media than are other art forms, and there are distinct regional differences. Painting clubs and classes can be terribly restrictive. They draw their leadership and jurors from a constricted pool, so members tend to conform to a narrow style to be juried into shows or awarded prizes. That can be either conscious or unconscious, but it inevitably leads to derivative or dated technique. When I first went to Manhattan to study with her,

Cornelia Fosslooked at my first exercise and said, “If this were 1950, I’d say, ‘Brava, Carol,’ but it isn’t.” That’s what came of learning to paint in Buffalo.

Of course in its own way Manhattan can be as provincial as anywhere else.

Cindy Zaglin studied at the

Art Students League in New York. She has never been one to tie herself blithely to someone else’s muse. “I was very unhappy. I was in class and would look at everyone’s realistic paintings and I could make mine look like theirs but it didn’t express me. I don’t care about the small details. I wanted to paint large swatches of color, use negative space, leave things out, replace things with color, and I was scared to do that.”

The problem with abandoning community is that one needs new ideas, and Zaglin struggles with how to maintain a healthy distance while still learning from others. “I still sometimes think what I’m doing isn’t ‘valid’. Sometimes I know when it’s working; sometimes I don’t. I do want to learn from others including realist painters. Painting freely or abstractly isn’t just throwing colors or shapes on a canvas; you still need to know how to draw.”

Then there’s the marketplace. Mid-level art buyers are a curiously reticent bunch, embracing new things only after they have the imprimatur of other collectors. Too many painters temper their inner vision to the marketplace. We have all seen insipid artists sell while brilliant ones struggle in the trenches.

|

|

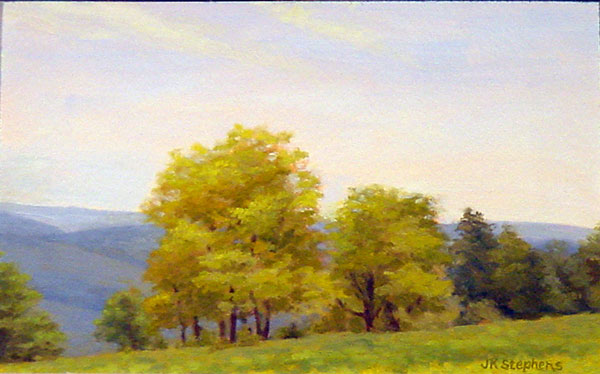

Spring Trees, oil on board, by Jean K. Stephens (image courtesy Oxford Gallery)

|

A decade ago,

Jean K. Stephens was a respected Rochester landscape painter, with impeccable technique born of a very disciplined mind and a passionate love of the land. I’d heard she’d been through a painterly rite of passage; a mutual friend showed me some abstractions she’d done that I found painfully honest. When I came across a small

nest painting of hers at

Shop One² at Global Village recently, I wondered what made this seemingly established painter give up what she knew, and perhaps more importantly, what she knew would sell.

“I couldn’t not do them,” she said of those early abstractions. She had undergone a process of deep-tissue massage that, she said, brought her back to her birth experience. “I woke up in the middle of the night and did something I never do: I just started flinging paint. It was certainly not planned. It just spilled out that first night,” she said. “The next morning I went in the studio and said, ‘What just happened here?’”

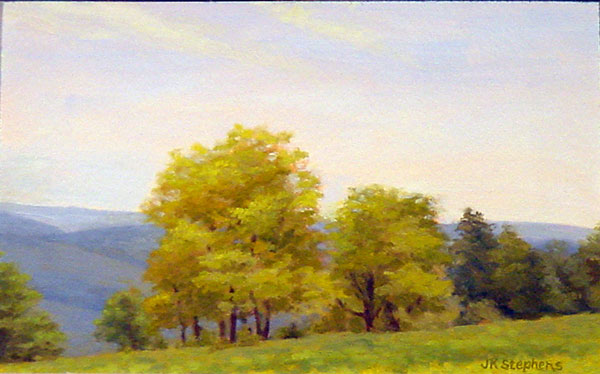

What happened was more complex than a spiritual or psychological discovery, since Stephens had recently moved, had entered menopause, and had sold the rural property that had made her ‘big vista’ landscapes possible. Even as she’s moved past this work, she says it was and is a “true expression of my feminine self.”

Stephens’ current work embraces both that feminine expression and her capacity for realism. “I was in Maine with a bunch of friends. We had rented a house and I was doing the typical plein air. On the last day I looked down at my feet and said, ‘There’s the Great Mother!’ In our trips to Maine, I had always loved the rocks, but I felt like this work was the culmination of everything I had done to that point.”

So what happens when a painter known for her delicate, luminous landscapes suddenly starts exhibiting rock paintings that look like vaginas? “There’s always a risk in putting something different on the wall,” acknowledges Stephens. “I can take that risk. I do the work for me, but if people connect with it, that’s even better.”

|

In and Out, oil on panel, by Jean K. Stephens (image courtesy of Oxford Gallery). The complete series can be seen here. |

Zaglin expressed a similar sentiment. “While I want others to be connected with my paintings I’m most interested in me being connected to my paintings. This year I started caring less about what others thought and started trusting that I did have a point of view.”

Last year was a time of personal crisis for Zaglin, and she thinks the upheaval changed her work. “Afterward, I decided I was wasting time not painting how and what I want,” she said. Which is, of course, true for all of us.

There’s still room in this summer’s Maine painting workshops! Check here for more information.