A graduate of Pratt Institute, Toby Gowing had a successful career as an illustrator, specializing in books for young-adult readers. From there, she moved to painting luscious still lives on Chinese antiques, which she sold throughout the Northeast.

When she told me she was retiring, I was baffled. Accountants retire; artists do not. Still, Gowing has a knack for listening to the still, small voice of God, and she has hardly been bored. Among other projects, she was asked by Louise Jasko of Monmouth Worship Center in Marlboro, NJ, to design windows for their newly built sanctuary. Gowing collaborates with glass artisans John Warda and Lynn Julian of White Haven, PA, who execute and install the windows.

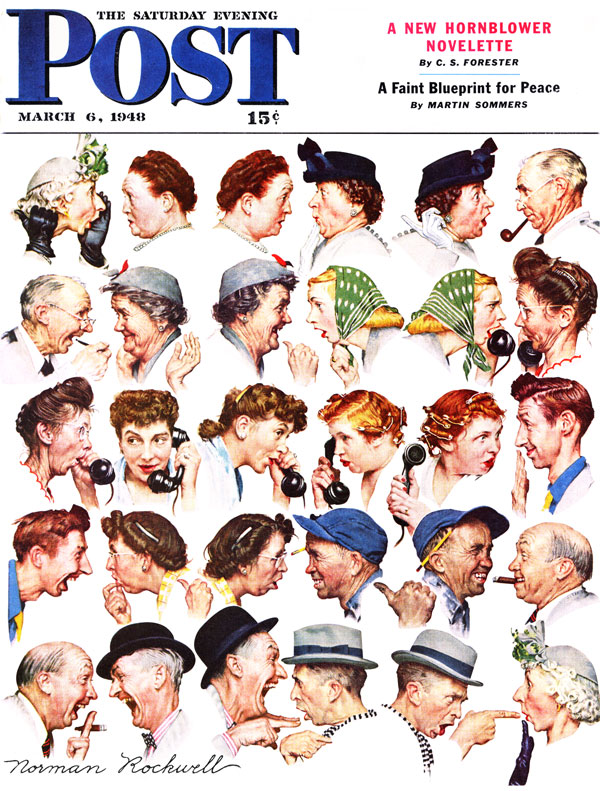

| Gowing’s painting for The feeding of the five thousand, above. |

Gowing feels her illustration background is the primary skill she brings to window design, and her painting and drawing chops allow her to accurately communicate her ideas to Warda. “He never asks, ‘Is this a fish or a flower?’ but he has told me when certain shapes or placements just won’t work,” she says.

How did she make the move away from oil painting? “I undertook a period of studying stained glass, particularly windows done by Tiffany studios, so that I could understand how to design for a new media,” said Gowing. “Tiffany was a painter, and his approach in windows is painterly. This appealed to me.”

|

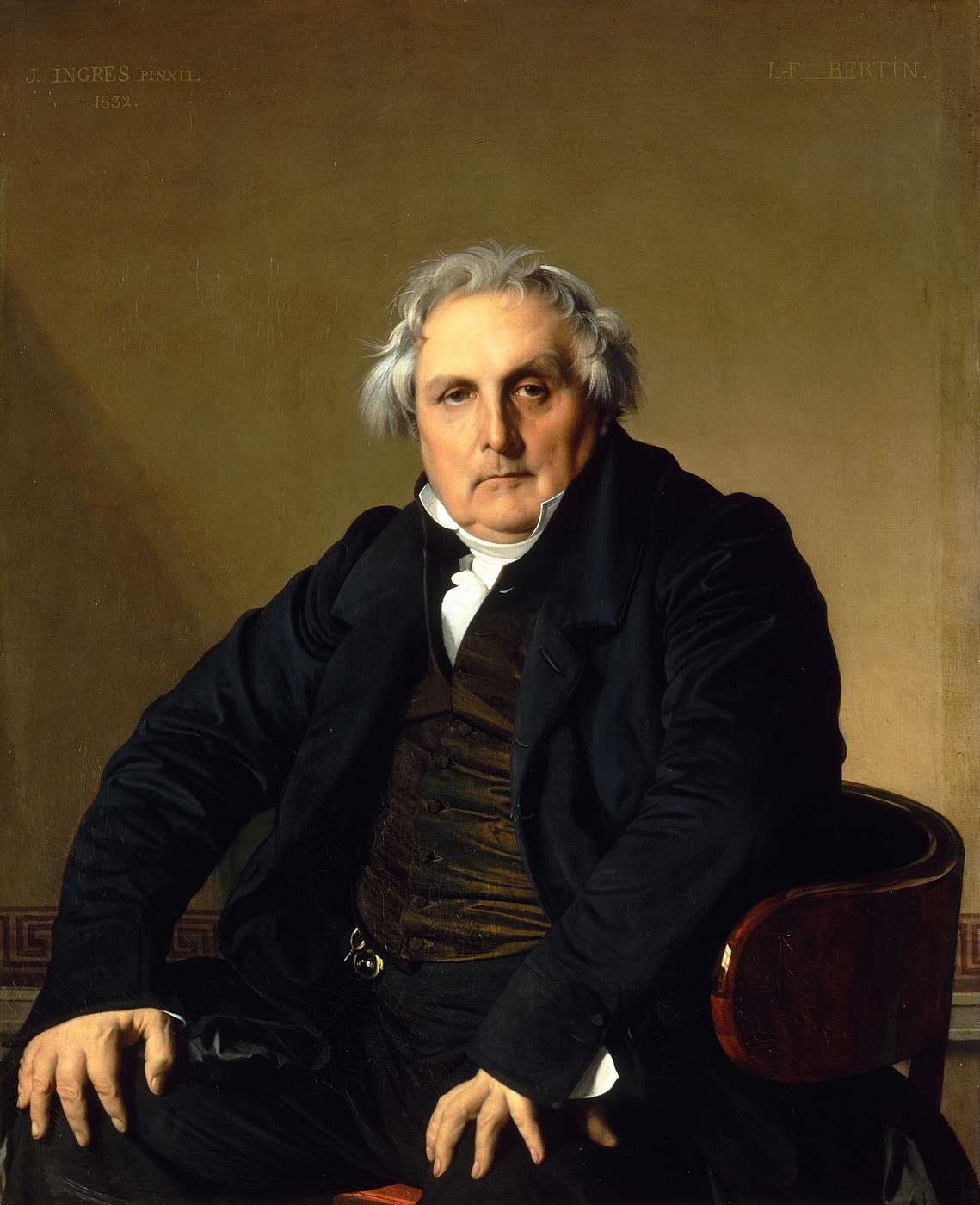

| Gowing’s painting for the Four Seasons window, above. |

The glass designer can’t think primarily as a painter. “When I design, I am always thinking, ‘How will this work out in glass? Will this line flow so that the leading will make sense and also add to the composition? Is it possible to make this shape in glass?’” said Gowing. She frequently talks with Warda as she works. “I ask him if a type of glass exists which would carry a particular image or create an effect. There are thousands of types of glass which may be purchased, but we are limited by budget and time.”

|

| John Warda installing The feeding of the five thousand at Monmouth Worship Center. |

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

.jpg)

.jpg)