|

|

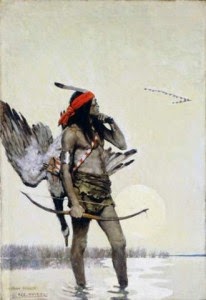

Dr. Seuss was a successful commercial artist when, at age 34, he wrote his first book, “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.” It was rejected by publishers dozens of times. He was in his late 40s when he began successfully writing and selling children’s books. He did this advertisement in the 1930s.

|

This past week I had conversations with two artists about the feasibility of being a full-time artist.

One is a woman with a young family, a mortgage, an MFA and a good (albeit temporary) job. Judging by the work I’ve seen, she has prodigious talent. If given the opportunity for a permanent position, should she take it? Or should she chuck that idea and try to work as a waitress nights and weekends so that she can still make art.

As a working mother, she is already doing two jobs. Adding a third job will be difficult, if not impossible. Until her kids are old enough for school, she’d be smart to do whatever pays best, and save money against the day she drops the day job and takes up painting again. In the meantime, she can carve out a small corner of her house and a few hours a week to nurture her talent, even if it’s by sketching in her spare time.

|

|

Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses, was the poster girl for late-life career changes, having turned to painting in her seventies. Here, Country Fair, 1950.

|

In essence, that’s what I did. I worked in the marketplace until I was in my late 30s, when a combination of life events made it possible—mandatory, even—for me to resume painting. (There was a time when our society acknowledged that raising children was valuable work. Now, childrearing is supposed to run silently in the background, taking no time or effort at all.)

One of my painting students has an MBA and work experience in an area of business analysis I won’t pretend to understand. She picked up brushes in response to a life crisis and in the process discovered that she has a real affinity for it.

On Saturday, we discussed what the next step might be for a person who wants to start selling paintings. As so often happens with these things, Life answered her question; she was approached about doing a solo show at a local venue.

|

|

Vincent Van Gogh didn’t actually start painting until he was in his late 20s, when he only had a decade left to live. Most of his masterpieces were created in the last two years of his life. Wheat Field with Crows, 1890, is generally accepted to be his last painting.

|

That’s a tremendous affirmation, but as we old-timers know, a show is just a doorway through which you enter the next phase of your work. She still has a long, hard slog ahead of her, but she has the character to endure it.

Neither of these women will find it an easy road. But in both cases, I think they will find something very valuable comes from it.

Come to Maine and learn to paint before it’s too late. I have two openings left for my 2014 workshop in Belfast, ME. Information is available here.