No discipline has suffered more from the internet than journalism. Its unemployment rate is higher than that of art historians, even though it was once the “something practical” that artists were told they should major in.

I worked as a stringer for a local paper in the late ‘80s. I made fifteen bucks a story back then, for which I sat through interminable board meetings. Said paper doesn’t even hire stringers any more. Evidently the water-and-sewer-line stories now gather themselves, and democracy in its most immediate form operates sub rosa.

“How do you publish photos on the internet so you don’t lose your copyright?” I was asked recently. (The writer was concerned about Facebook.) The short answer is that we give Facebook a non-exclusive, transferable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any content we post. However, we don’t negate our ownership; that’s protected by law.

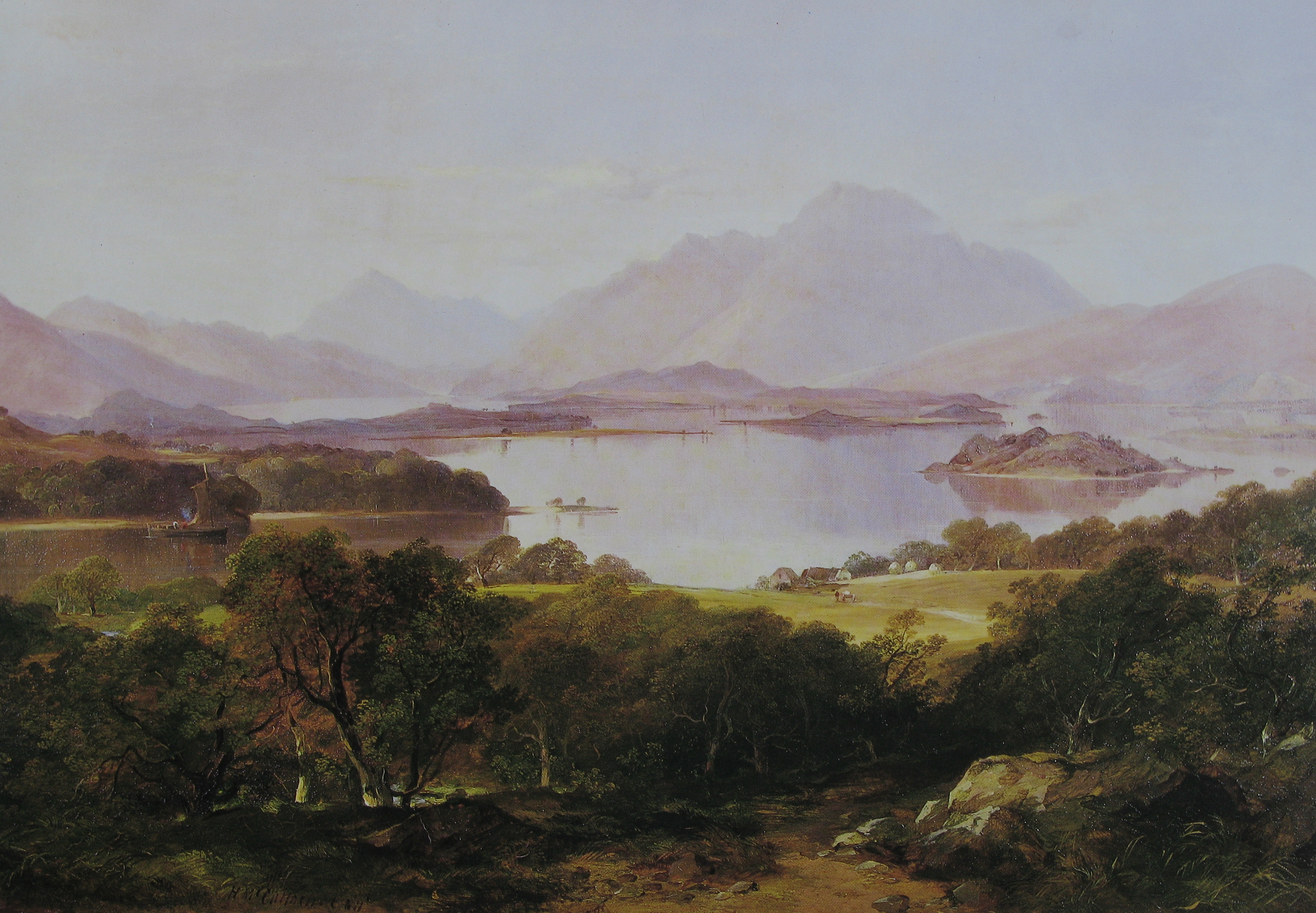

| The same scene in a photo, more or less. Do whatever you want with it; I don’t care. Photos are a dime a dozen on the internet. |

Having said that, our copyright is probably worthless, because photography itself is devalued. Today’s point-and-shoot cameras take better pictures than most trained photographers could back in the age of film. Unless you’re shooting events for a fee, are particularly gifted, or got extremely lucky and caught the Duchess of Cambridge nursing Prince George in the buff, you may as well set your privacy controls to zip and let ‘er rip. It’s difficult to protect photos on the internet, and many news sources have given up trying.

Which brings me to a curious anomaly about the internet: it’s better for painters than for photographers. No screenshot of one of my paintings will ever compare to the original. However, the character of a good painting is implied well enough in a photo that potential buyers can see what they’re getting. That means that the same qualities that make the internet so good for ripping off people’s photos make it a great platform for promoting paintings.

Oddly, one sees a similar thing in the writing disciplines as well. I can hack almost any news source, but if I want to read a novel, I go through the normal licensing channels to download it to my Kindle or—gasp—read a book printed on paper. Novelists can and do use the internet to promote their works, and we consumers willingly pay them for their intellectual property. Imagine that.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

_(RA)_-_Travoys_Arriving_with_Wounded_at_a_Dressing-Station_at_Smol,_Macedonia,_September_1916_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

,_by_Velazquez.jpg/521px-Las_Meninas_(1656),_by_Velazquez.jpg)