|

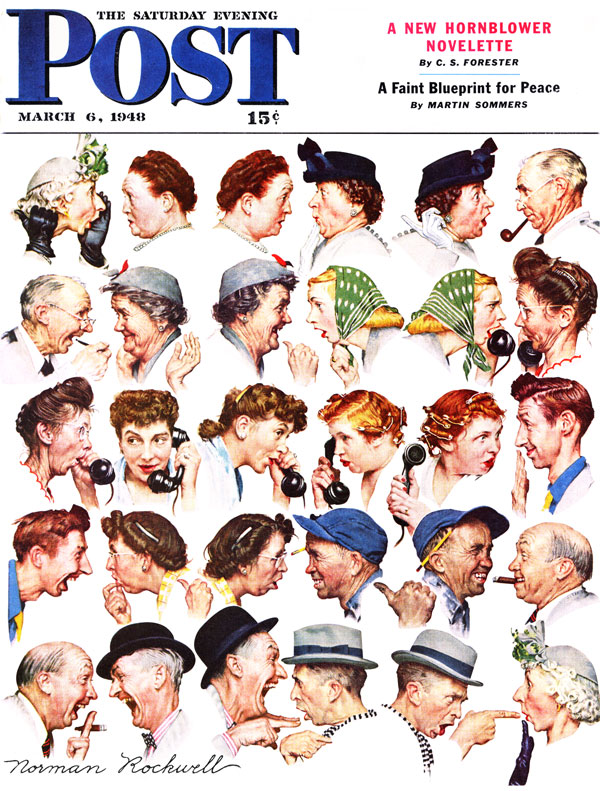

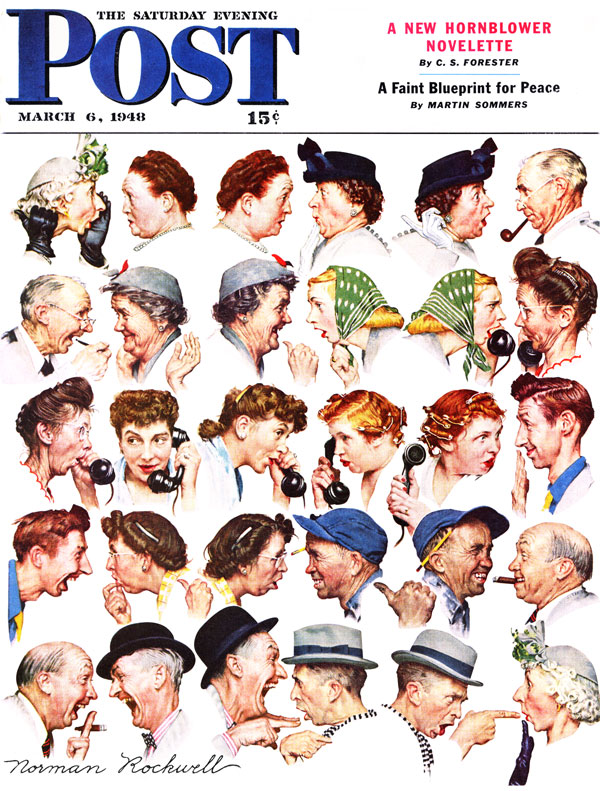

| Freedom from Want, Norman Rockwell, 1943 |

This Thanksgiving Day the average American will consume more than 4500 calories,

accordingto the Calorie Control Council. I’m all for eating right, but I think the capacity of our nation to throw an annual bash is an unequivocally good thing.

Thanksgiving is the most universal of American holidays—celebrated by people of all religions, by new immigrants, and by wanderers like my friend Martha in Edinburgh, who has located a 6 kg. turkey and a circle of friends to share her holiday.

|

| Freedom of Worship, Norman Rockwell, 1943 |

Perhaps that’s why Norman Rockwell chose it to illustrate Freedom from Want in his Four Freedoms series. The painting celebrates family, love, and happiness. Critics who call it an illustration of American overconsumption perhaps don’t notice that there is almost no food on that table. There is no wine; there is only water in plain, clear glasses. The black suit and white table are almost Puritan in effect. What abundance there is comes straight from the hosts’ hands, and the joy around the table comes from each other.

|

| Freedom of Speech, Norman Rockwell, 1943 |

The arresting composition may be why this painting is one of Rockwell’s enduring favorites. Many of his covers for the Saturday Evening Post were done as one-dimensional knock-outs, with no perspective to speak of. This view from the bottom of the table, with its luminous white-on-white table set starkly against Grandpa’s black suit, is a masterwork of composition. (Rockwell said that it was the easiest of the four paintings.)

|

| Freedom from Fear, Norman Rockwell, 1943 |

Rockwell painted the Four Freedoms in seven months’ time, during which he lost 15 lbs. They were based on President Franklin Roosevelt’s Annual Message to Congress in 1941, which were dark days for those in opposition to Nazi Germany. As we take time from holiday preparations, it’s worth contemplating Roosevelt’s words:

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

.jpg/594px-Paintings_from_the_Chauvet_cave_(museum_replica).jpg)