At times, the Great White North reaches down and touches us with its living whiteness and its freakish cold.

Long before there were cell phones, I routinely painted outside in winter. One year, I committed to plein air painting six days a week regardless of weather. In western New York that can be wicked indeed. That year made me into a painter. It is also how I moved from being an amateur to a professional. I had so many paintings lying around, I was forced to sell them.

|

|

The Artist in Greenland, 1935, Rockwell Kent, courtesy Baltimore Museum of Art |

Rockwell Kent first visited Greenland in 1929, saying the visit “had filled me with a longing to spend a winter there, to see and experience the far north at its spectacular worst; to know the people and share their way of life.” In 1931, Kent built himself a hut in in the tiny settlement of Illorsuit, a village north of the Arctic Circle. He wintered and painted there. As a socialist, Kent was enamored of Inuit society, considering their little village a kind of utopia.

Kent later said that his year in Illorsuit was the happiest and most productive time of his life. Among his other pursuits, he acquired a sled and team so that he could make even more remote painting and camping expeditions. In a witty aside, Kent painted himself painting an iceberg, above.

|

|

The Sea of Ice, 1823–24, Caspar David Friedrich, courtesy Hamburger Kunsthalle. The only sign of human activity is the shipwreck. |

Friedrich set out a manifesto for painters that still rings true: “The artist should paint not only what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also refrain from painting that which he sees before him. Otherwise, his pictures will be like those folding screens behind which one expects to find only the sick or the dead.”

The only hint of human activity in The Sea of Ice, above, is the subtle, moralizing shipwreck. This is very different from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow, which is a parade of everything medieval man did in the wintertime.

|

|

The Hunters in the Snow, 1565, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum |

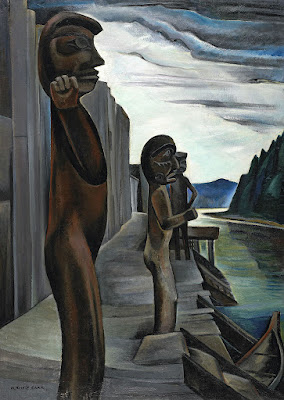

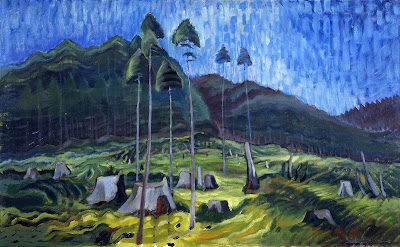

Lawren Harris was one of the driving forces behind the Canadian Group of Seven, and the most elastic of them. He went from impressionism to art nouveau realism to complete abstraction in two decades. His final break with realism occurred in the early 1930s, after he visited and painted in the Arctic.

Harris believed in the arctic as a living force: “We are on the fringe of the great North and its living whiteness, its loneliness and replenishment, its resignations and release, its call and answer, its cleansing rhythms. It seems that the top of the continent is a source of spiritual flow that will ever shed clarity into the growing race of America.” His painting at top is a narration of what happens when that power spills into the northern US and Canada.

Four different painters from different places and times, but they’re all telling stories of winter in very inventive ways. Could we do half as well?