With apologies to Robert McCloskey

|

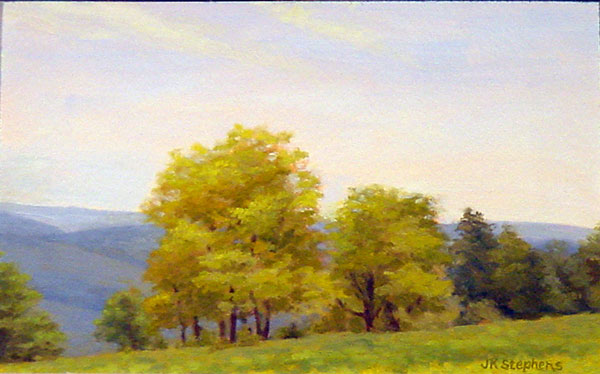

| “Sunset at Marshall Point,” 8X6, oil on canvasboard, private collection |

People say, “Paint what you know,” but I’m more for knowing what I paint. That said, my knowledge of Maine has until now been surface deep. I’ve painted in Eastport and Lubec and the mid-coast region, but not in the last few years, and never with the kind of intense concentration that you get from being in the same place day after day. I freely admit that I don’t understand the Maine landscape with the same intensity that I understand Keuka, but that doesn’t mean I can’t learn.

|

| Sunset over Penobscot Bay. |

I’ve been invited to teach plein air in mid-coast Maine next summer. The only way from here to there is to pull out my brushes and paint there, intensively, day after day. Most sane people do NOT do that in November, but I believe in striking while the iron is, er, stone cold.

Cold it is during the two weeks leading up to Thanksgiving, no matter where in the Northeast you’re painting. One morning I was painting on a commercial wharf and thought it was warming up enough to doff the gloves, until I reached for a baby wipe and found it frozen solid to the ground. (An aside: the good news about painting all day in that kind of cold is that you sleep like a baby.)

|

| “Pine trees at sunset near Owl’s Head, ME,” 8X6, oil on canvasboard, private collection. |

Maine is iconic, and there are subjects which are almost verboten because they are clichés—lighthouses, lobster boats, surf, lobster traps, and buoys. Yet those things are also integral to what Maine is, and in the hands of good painters, are both transformed and transformative. Maine resonates with many of us precisely because it is a place whose hard work is on display. We Americans revere and respect work. To ignore that would be almost as clichéd as the worst lighthouse painting.

|

| “Surf,” 8X6, oil on canvasboard, available. |

I frequently fall into two compositional traps when painting the ocean, something I never worked out satisfactorily before this trip. The first is getting caught in the perfect ellipse of the shore, and the second is the triangle formed by ocean silhouetted by land. After ten days or so of fighting this, I drove two hours to see a wonderful show, “

Weatherbeaten: Winslow Homer and Maine,” at the Portland Museum of Art. As one entered, one first saw “

The Artist’s Studio in an Afternoon Fog,” which is owned by Rochester’s own Memorial Art Gallery. This painting is an old friend, and one I frequently use to teach composition.

Homer used two devices to organize his Maine paintings: a strong dark diagonal, and vast simplification. I use that diagonal in figure-painting all the time; why did it never occur to me as a solution here?

Maine in November bears little resemblance to the traffic jam that is US 1 in July. The plein air painter has to know two things—how to get off the beaten path, and where to find toilets and coffee. I spent much of my two weeks figuring out these details. Much of my painting was, therefore, less about painting than about planning to paint. But then I would see seals gamboling in the ocean, and it was about the joy of God’s creation and my grateful heart.

|

| My wee little paint kit on a cold day in Belfast, ME. |

The

Farnsworth in Rockland has to be flat-out the best museum in a city of its size (

7,297 people, I kid you not), anywhere. When I visited, they were simultaneously featuring Louise Nevelson and

Frank Benson, which was a stretch for my limited brain. I was most moved and surprised by the

Jamie Wyeth-Rockwell Kent show. I am a big fan of surrealism in literature, but in painting it generally leaves me cold. Wyeth has an iteration of

this painting (in oil) which is simply the best surrealist painting I have ever seen. I was also quite taken by his

The Seven Deadly Sins as expressed through seagulls.

|

| Near Port Clyde, ME. |

I am about the same age as Jamie Wyeth and like him was taught to paint by my father. (There, obviously, the similarity ends.) I was rather surprised to find in his mature work such a strong resonance with his grandfather, the great narrative painter NC Wyeth. All those Wyeths are story-tellers, but there’s a romanticism that skips from grandfather to grandson.

In my wanderings, I met Robin Seymour, gallery manager for

Eric Hopkins, who is a joyful, lyrical and yet very intellectual painter. Robin is a true art historian, worlds away from the typical gallerista, and I got a tremendous kick out of talking to her. I also met Hopkins himself, who demonstrated looking at things upside down by lying on his back on his credenza; it’s a sign of the Mainer’s resilience that he was able to get back up. Robin introduced me to her neighbor,

Yvette Torres, who in turn introduced me to the fantastic work of

Winslow Myers. Later that week, painter

Alison Hillof Monhegan took me along to her weekly figure session, which was in Yvette Torres’ gallery. When life moves in circles like this, it’s simply wonderful.

|

| “Marshall’s Point,” 12X16, oil on canvasboard, available. |

To say I’m looking forward to teaching there next year is to vastly understate the case. Watch this spot.