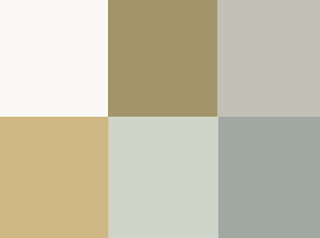

In winter, we’re in warm light from sunup to sunset, because the sun never really climbs very high in the sky. That’s our payoff for putting up with this weather.

|

| Three photos of the golden hour, courtesy of Jennifer Johnson |

The golden hour is that period after dawn and before sunset when the light is warm and the shadows are long and blue. The farther north you go, the longer the golden hour lasts. In winter in the northern United States, we’re in warm light from sunup to sunset, because the sun never really climbs very high in the sky. That’s our payoff for putting up with this weather.

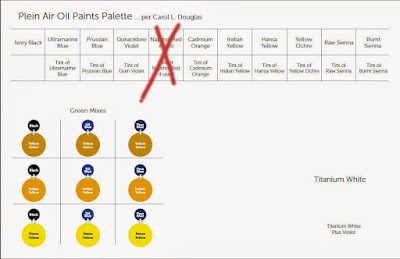

Most of us prefer to paint that winter light from the comfort of our studio, but cameras lie. That’s the same black glove, below; the image on the left is with a cellphone camera and the one on the right is with a DSLR. In attempting to correct exposure, the cellphone is interpreting that black as purple.

|

| Two photos of a black glove, courtesy Dwight Perot |

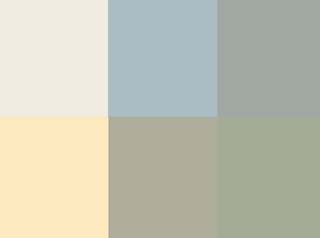

So too does your eye-brain connection see things interpretively. You may see the same blue shadows in the three photographs at top, but I’ve sampled them and they’re not the same at all. In fact, they’re not even blue, but rather three variations of a soft blueish-grey. Your mind is interpolating what it knows to be true, which is that those shadows are cool. In this case it’s better to trust your mind than the hard ‘facts’ of camera and laptop.

What we call light is really the narrow band of electromagnetic waves that our retinas can perceive. This narrow band is comprised of the colors of the rainbow, or what we sometimes call ROY G BIV. (There really isn’t an indigo; it’s there so that Roy has a pronounceable surname.) Each of Roy’s color names corresponds to a specific wavelength. For example, blue is about 475 nm; red is about 650 nm.

When the whole visible light spectrum strikes your eye at the same time, you perceive white. This is not a color in itself, but the admixture of a bunch of colors. In the real world, this is never a pure mix. The atmosphere bends light just like a prism does, so what you see is always tinted. The light might be gold and peach at sunset and cool at midday. Impurities in the atmosphere also give us the energetic indigo-violet of the far distant hills.

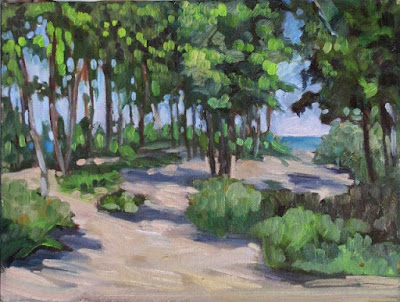

|

|

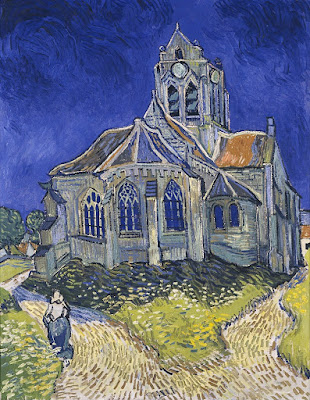

Valencian Fishwives, Joaquín Sorolla, 1903. Here the light is cool and the shadows are warmer. |

The farther away something is, the more likely dust has filtered out the longer wavelengths, i.e., the warm colors. That’s why your plein airpainting teacher keeps telling you that the reds drop out first, then the yellows, leaving you with blue.

Just as all the colors together form white light, the absence of light is total blackness. But unless you’re in a cave or darkroom, that’s a theoretical construct. There’s always reflected light bouncing around in the shadows, and that light gives the shadows its color. It’s never black and it’s unlikely to be grey, either.

If the color of the light is warm, the color of the shadows is almost always going to be cool, and vice-versa. Knowing this and identifying the color of the light and shadow is the first step to a good landscape painting.

The exception to this is an object in filtered light. Its shadows and lighter passages will be variations of the same color temperature. This is how we instinctively know that something we’re seeing is under an awning, for example.

Study the Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla to understand the color of light. He was a master at painting white fabric in a variety of circumstances, and comparing the light passages to the shadow passages will tell you much about managing the color of light in your painting.