Wildfire is threatening an area I know and love. It’s a reminder that nothing lasts forever, even the trees and hills.

|

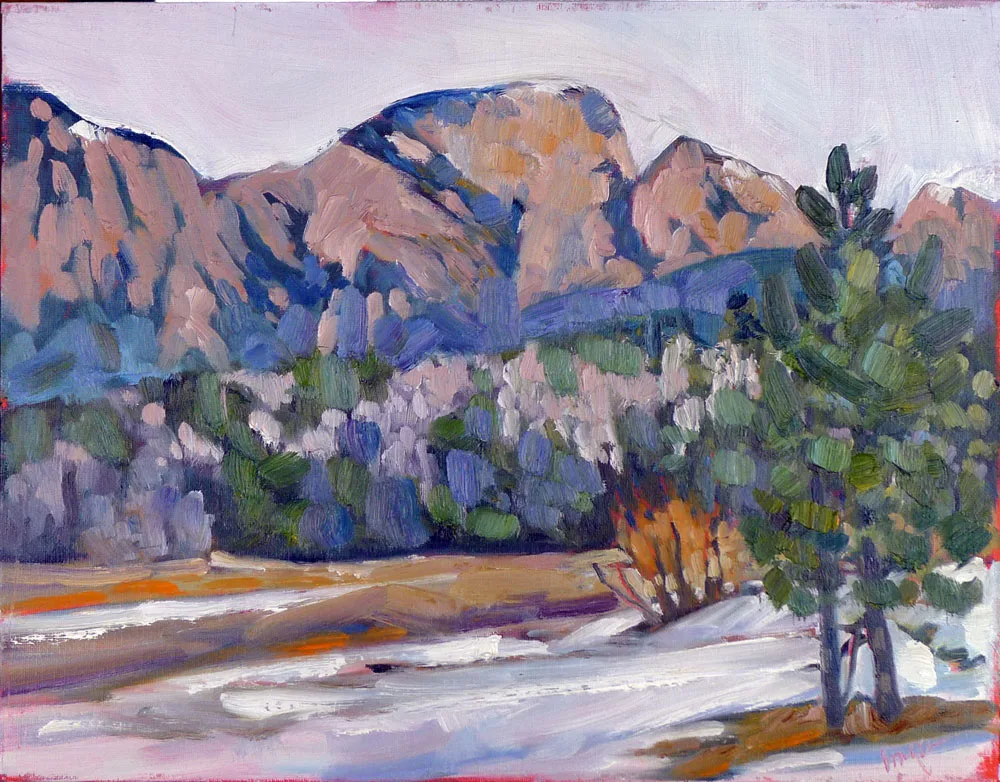

| Hermit’s Peak from El Porvenir, Carol L. Douglas, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time recently watching the wildfire at Hermit’s Peak in New Mexico. “Much of the fire’s growth is in thick, heavy timber and steep, rugged terrain,” writes officialdom. That is, if anything, an understatement. I’ve painted in El Porvenir with my buddy Jane Chapin. The area is desolate.

As sad as the current fire destruction is, it’s where the fire is heading that concerns me. It’s been burning slowly toward the villages of Upper and Lower Colonias and county road B44A. The Pecos River basin is just a few miles from the fire’s edge.

|

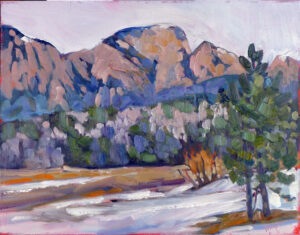

| Upper Reaches of the Pecos River, Carol L. Douglas, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

This is where my Gateway to the Pecos Wilderness workshop is centered, and I’ve come to know and love this tiny slice of Creation. It’s deeply wooded, high, fresh and mountainous.

Of course, I’m worried about Jane, who is in the evacuation ‘set’ zone. However, Jane’s the person who extracted us all from Patagonia after lockdown. There’s nobody I’d rather be in a crisis with.

|

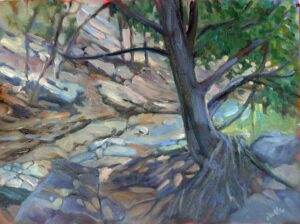

| Old farmhouse in Pecos, NM, Carol L. Douglas, oil on archival canvasboard, available. This is one of the historic structures in the evacuation ‘set’ area. |

The fire started as a prescribed burn lit on a windy April day. It’s now burned out of control for five weeks and shows no sign of imminent containment.

The terrain is extremely inaccessible. “It has more roads on the east side of the ridge but the Pecos Wilderness side is forest roads. They’re often a challenge even for a 4-wheel-drive truck,” Jane told me. “They are steep, full of big rocks, tight switchbacks and big drop-offs, and there’s no turning around.”

|

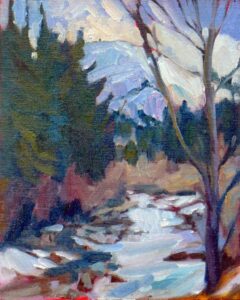

| Dry Wash, Carol L. Douglas, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

It was the area beyond Lower Colonias where Jane and I scratched the tar out of her truck trying to back away from a steep drop. There’s no need to go off-roading for adventure; the roads themselves are terrifying.

“We now have over 1900 firefighters on this fire, most of whom are unfamiliar with the area and are sleeping on the ground in tents in fire camps,” Jane said. That’s hard work, complicated by the natural fauna of the area: bears, bobcats and mountain lions will be on the move, along with whatever horses, dogs and cattle may be caught within the fire line. Lest you think that’s an exaggerated risk, a soldier was killed at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage, AK on Tuesday by a grizzly sow protecting her cubs. Where civilization and nature collide, stressed animals sometimes behave erratically.

|

| Snow at Higher Elevations (downdraft), Carol L. Douglas, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

This week, we’re reading about mansions burning in Southern California, but those people have the resources to rebuild. In contrast, San Miguel County, NM, is poor. A quarter of the population live below the poverty line. That makes them voiceless in modern society. They’re unlikely to be able to challenge the Forest Service about the wisdom of ‘controlled’ burns, and this is the second time in seven years where a prescribed burn has gotten loose in this area.

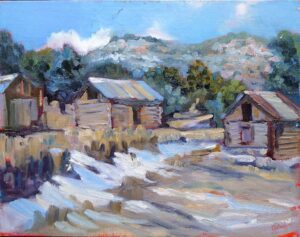

|

| Log barns, Carol L. Douglas, oil on archival canvasboard, available. This historic farmyard is in the evacuation ‘set’ area. |

But that’s all politics. What saddens me, deeply, is the potential destruction of a place I love. As Jane said, it seems somehow wrong to pray that the wind shifts and takes the fire to the east. If her home is saved, someone else’s will be destroyed. Instead, I pray for rain.

Nothing lasts forever, even the seemingly immortal forests and hills. That makes it even more imperative to get out and look at them—and paint them if you will—while you can.