Painting is a lifelong exercise in self-guided learning.

|

| Clary Hill Blueberry Barrens, watercolor on Yupo, available through Maine Farmland Trust Gallery, by Carol L. Douglas |

A student asked me why I teach all levels in my classes. Indeed, adding a brand-new painter to the group can sometimes be difficult, as I need to spend a little more time with that person at the start. I’ve found, however, that almost everyone needs the same lessons repeatedly. Painters make the same errors at almost every level—of value, color-mixing, contrast, line, and focal points. It takes a surprisingly amount of time to convince students of the value of process, including value sketches and drawing.

My own experience in taking master classes hasn’t been good; they’ve been less about mastery and more about marketing. That’s not to indict all painting teachers, but unless the teacher knows you in advance, they know very little about your painting level before you start the class, even with portfolio review.

| Clary Hill Blueberry Barrens, oil on canvas, available through Maine Farmland Trust Gallery, by Carol L. Douglas |

With twelve or fewer students in a class, I have time to meet each person where they are and encourage them a little farther along the road. This is very intensive, and I blow it more than I like. Yesterday I had a painter whom I should have pushed harder on establishing a focal point, but I didn’t realize that until dinnertime.

I still occasionally take classes myself, although it’s not common. It happens when I run across a painter who’s doing something I want to master. I took Poppy Balser’s watercolor workshop a few years ago, because Poppy can make a line of dark spruces shimmer against the sea. I wanted to know how she made that value jump in watercolor.

There are other painters I would like to learn from. Dick Sneary and Dave Dewey are both consummate watercolorists, and I admire their drafting and composition skills tremendously. Likewise, I admire Lois Dodd’s ability to drive to the emotional nut of a scene by removing all extraneous matter. And I often return to Clyfford Stillto think about composition.

|

| Part of my class on Clary Hill, photo courtesy of Jennifer Johnson. |

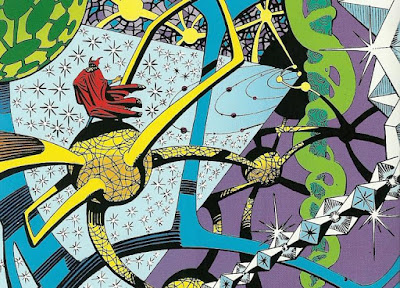

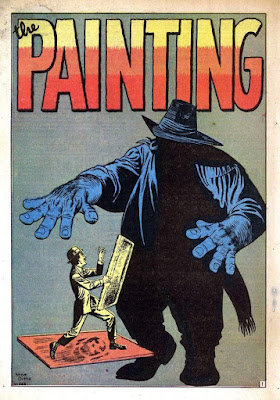

An old and reliable way to learn is to copy master works. I recently started drawing frames from Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko comic books. This led to copying images from the first great cartoonist, Peter Paul Rubens.

But, in general, I’m done studying with others. “How do you know when that happens?” my student asked me. In my case, I realized that the time I was spending traveling to the Art Students League of New York from Rochester would be better spent in my own studio working.

“What comes after I’m done studying with you?” she asked. Go out and paint (which students should be doing anyway). If you like the social side of classes, find a painting buddy or join a painting group. We make the most progress when we’re picking up our brushes several times a week.

|

| Jean Cole’s painting on Clary Hill. She just came back from my Pecos workshop. The goal ought never to be to make ‘mini-me’ painters, but to develop each person’s own style. |

I’m doing a FREE Zoom workshop on Friday, October 2 at 5 PM. Consider it Happy Hour, and join me with a glass of wine, a spritzer, or whatever else. We’re going to talk about studying painting. What should students expect to get from a workshop or class? What should teachers offer? Have you always wanted to try painting but been afraid of classes? Are you taking classes but want to get more out of them? Join us for a free-ranging discussion.

While this is in advance of my Find your Authentic Voice in Plein Air workshop in November in Tallahassee, everyone is welcome. There’s absolutely no charge or obligation. Signups are already brisk, so register soon!