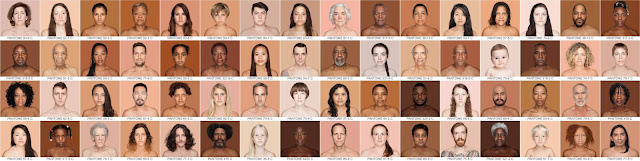

We come in an amazing array of colors, but they can all be mixed with the same narrow array of pigments. Why is that?

|

When Brazilian photographer Angélica Dass was six, her teacher told her to use the skin-tone crayon for a drawing. “I looked at that pink and thought, how can I tell her this is not my skin color?” That night, she prayed to wake up white, she toldNina Strochlic of National Geographic.

If you have close friendships with non-white Americans, you have heard variations on this riff. That’s particularly true if you’re of an age when blacks were invisible in commercial culture. When I was a kid, there were no African-American dolls in the stores, and few children’s books with black protagonists.

|

|

Iron oxide yellow, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

|

There is no underlying biological construct of race. The idea of separate races was the brainchild of a 19th century physician and scientist, Samuel Morton. He rejected the Creation Story in Genesis and argued, instead, that each of the five different races in the world was created as a separate species. (Remember that the next time someone tells you that believing in the Bible is somehow anti-science.)

Morton claimed that he could define the intellectual ability of a race by its skull capacity. Caucasians were, naturally, at the top of his chart. Negroes were at the bottom. His theories carried a certain amount of weight in American culture until they were shredded by the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould in The Mismeasure of Man.

|

|

Burnt sienna pigment, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

|

But back to Angélica Dass. She married a Spaniard, and she began to wonder about the question of human skin color. In 2012, she started photographing members of her and her spouse’s families. She then matched a strip of pixels from their noses to a Pantone color card. Humanae arose from this. It now includes 4,000 portraits from 18 different countries.

“So-o-o-o-o many colors of skin, not just black, white, red, or yellow,” the reader who sent this to me commented. That’s true, but it’s also true that all human skin colors can be made with just a few pigments.

There’s really no such thing as white skin color, black skin color, or Asian skin color. They are mixed with the same array of paints; we just control how much white paint we add to the mix. My guide to mixing skin tones can be found here, but it’s also possible to mix all human skin tones with just iron oxide pigments. These range in tone from yellow through orange and red to black.

|

|

Iron oxide pigment, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

|

Iron is the most common element on earth, comprising almost a third of our planet’s total bulk. The second most-common element is oxygen. Iron oxides are chemical compounds of those two elements. They are extremely widespread in nature, appearing as rust and hemoglobin, among many other things. Humans use them in the form of iron ore, from which much of modern civilization was built. Iron oxide also gave us mankind’s first pigments, in the form of ochre, in use for 100,000 years. The iron oxide pigments are not only plentiful, they’re very safe.

|

|

Iron oxide powder, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

|

Our coloration is intimately related to our planet. We are creatures of the earth, tied to the earth, and created here. Our pigmentation points not only to that, but to the universality of mankind, despite the artificial and abusive construct of skin color.

It’s about time for you to consider your summer workshop plans. Join me on the American Eagle, at Acadia National Park, at Rye Art Center, or at Genesee Valley this summer.