Restoration and destruction both start with a spark. Which will it be?

|

|

Notre-Dame on fire, April 15, 2019, courtesy LeLaisserPasserA38, Wikipedia.

|

I’ve never been to France, a deficiency I always meant to correct someday. Now I will never see Notre-Dame de Paris. Whatever is rebuilt there will not be the 800-year-old monument to a nation and a faith that stood there on Monday morning.

Before there were Christians, before there was a France, there was a Roman temple to Jupiter on the Île de la Cité. Around the time when Gaul was transferred from the Romans to the Franks, a basilica was erected on the site. It was dedicated to Saint Stephen, the first martyr of Christianity. In 857, it was remade as a cathedral (which is the seat of a bishop). Successive remodelings attempted to keep up with the growing population of Paris, always unsuccessfully.

|

The Pillar of the Boatmen is a monumental Roman column from the first century AD. It was found re-used in the 4th century city wall on the Île de la Cité, and indicates a shrine on this site before the conversion of Gaul. This block represents the gods Tarvos trigaranus and Vulcan. Courtesy Musée National du Moyen Age, Thermes de Cluny.

|

In 1160, Bishop de Sully embarked on an ambitious plan to raze the Cathedral and replace it in the trendy new Gothic style. The cornerstone was laid in 1163 in the presence of King Louis VII and Pope Alexander III. De Sully lived long enough to see the basic structure in place; his successor built the transepts and most of the nave. The west façade and the rose window were not finished until the 13th century, by which time the transepts were being remodeled. Better supports were added in the form of flying buttresses, one of the great engineering developments of the Middle Ages.

|

| The complex, multi-tier flying buttresses of Notre-Dame. |

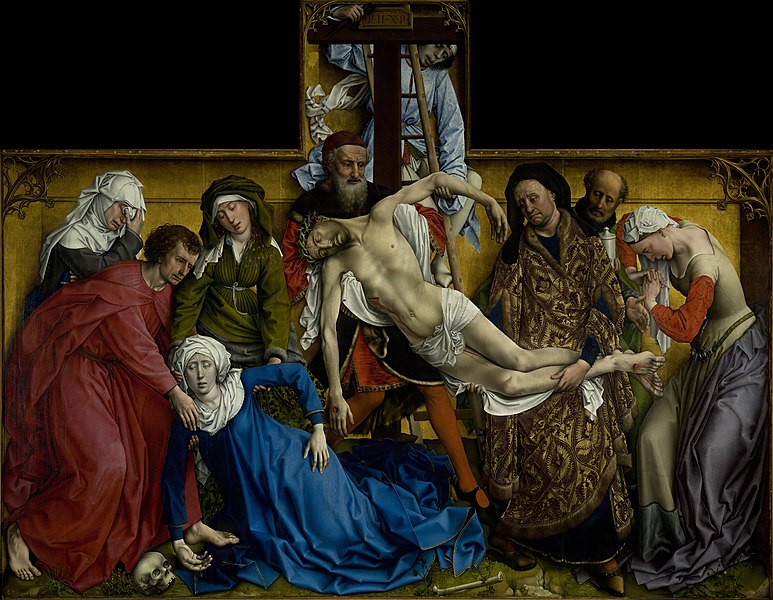

This fire is not the first hit Notre-Dame has taken, but it’s the most serious. Huguenots destroyed some of its statuary in the iconoclastic fury that swept Europe in the 16th century. The Sun King updated it in the severe classical tastes of his time. As Robespierre and his radical brethren tried to stamp out Christianity during the French Revolution, the Cathedral was dedicated first to the Cult of Reason and then to the Cult of the Supreme Being. Of course, its treasures were destroyed or plundered. Twenty-eight statues of biblical kings on the west façade, mistaken by the mob for statues of French kings, were beheaded. The remaining statuary on the west façade, except for the Virgin Mary, was destroyed.

|

|

The Coronation of Napoleon, by Jacques-Louis David, 1805-07, courtesy of the Louvre.

|

Eventually, the church settled into life as a warehouse. Then Napoleon Bonaparte banned the cults and restored Catholicism. He was coronated at Notre-Dame in 1801.

By then, the Cathedral was a half-ruined mess. In 1844, an ambitious, 25-year reconstruction project ended with the Cathedral being renovated to its modern condition. It survived two World Wars mostly unscathed.

|

|

Notre-Dame in the Late Afternoon, 1902, Henri Matisse, courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery

|

Modern Catholics may feel that their church has been burning down around them for quite a while now. They’re under assault from within and without. In another sense, that’s true of the church as a whole, as Christians suffer martyrdom in unprecedented numbers worldwide. The blaze assumed a metaphorical power, coming, as it did, at the start of Holy Week. This is Christendom’s most solemn and significant observation.

The fire corresponded with the cremation of my missionary friend, Lori Delle Nij, in Guatemala. This morning she and Notre-Dame are in ashes, as you and I and everything else here in the Earthly City will ultimately be.

But it’s important to remember how Holy Week ends. I was moved by images of Parisians on their knees singing hymns as their Cathedral blazed in front of them. We are all promised Resurrection. “God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform,” wrote the poet William Cowper. Let it be so.