“Historic Fort Point,” by Carol L. Douglas

While it was fresh in my workshop students’ minds, I shot pictures showing the step-by-step progression of a painting. I took these while participating in the

Third Annual Wet Paint on the Weskeag this past weekend.

The site I chose was the ruins of

Fort St. George, overlooking Thomaston. Not much remains but a raised berm, but it is peaceful, pretty, and shadowed by oaks. I parked by

Wiley’s Corner Spring and eyeballed the stream. It looked perfectly wonderful, but I have been fooled by drinking-water sources before. Putting caution before curiosity, I resisted and turned to hike the half-mile to the fort site. It was an easy trail, but I was glad I had my

super-light pochade box.

I settled down on a rock outcropping, bracing my tripod below me on the uneven boulders.

My sketch.

The problem with rocky outcroppings along water is that they can create unbalanced compositions. All the weight is on the land side. On a grey day, there’s little sky action to counterbalance that.

I never use viewfinders of any kind. To me the most exciting part of painting is figuring out how to transfer all that grandeur into an arresting composition. The rest is just details.

First draft of a drawing.

After I had a composition I liked, I transferred it to my canvas. I generally copy my sketch rather than drawing again from the view. After I have the major pieces in place, I go back and redraw to conform to reality.

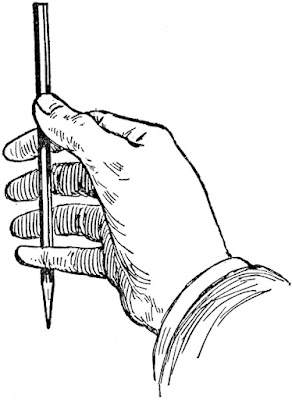

My palette.

I always mix my green matrix and tints of my pigments before I start painting. It keeps my color clean. And, yes, I use a palette knife.

For more information on how I chose this palette, see the pigment and color theory posts

here.

Next, I map in the colors.

I’m mostly concerned with drawing accuracy and color when I do my underpainting. This is a color map made with thin layers of paint and a minimal amount of solvent. I want it as dry as is possible when I do the next layer. Odorless mineral spirits or turpentine dry faster than linseed, walnut or poppy oil.

If anyone suggests using medium or oil at this phase of your painting, back away slowly. One of the first mantras of painting is “fat over lean.” That means applying oily paint over less-oily paint to create a stable, elastic paint film that doesn’t oxidize. Paintings made this way last for centuries.

I am familiar with some teachers who encourage their students to coat the surface with medium and paint into it to create a sort of faux

luminism. These paintings are drowning in oil and varnish, which will darken and crack over time. It’s terrible technique and should not be encouraged.

This is more or less the point at which I start using larger amounts of paint and add medium.

Start adding medium when you start adding paint volume. Go light on the stuff. It can makes an unmanageable soup very quickly. I use a larger brush than you would expect. In the painting above I used a #8 filbert throughout, only pulling out a larger flat to smooth down some surfaces.

As I headed back to the

Kelpie Gallery to turn in my finished painting, I took one more long look at Wiley’s Corner Spring. Oh, heck, I thought. Why not live dangerously? The water was smooth and sweet, and created no aftershocks.

The finished piece won the Juror’s Choice award. If I’d expected that, I’d have pressed my blouse.

That was important, because by the time you read this, I should be most of the way to Montreal, from whence I am flying to Edinburgh. I plan to do some simple watercolor sketches along the way, but until I return, keep on painting… and go light on the medium, for heaven’s sake!