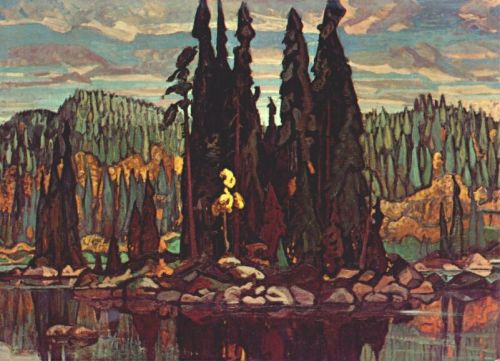

Schoodic Point breakers by Lynne Vokatis (finished).

A visitor mentioned that Acadia’s Schoodic Peninsula seems much busier than it has in other years. I’d been thinking much the same thing. If so, that means the National Park Service’s investment in the

Schoodic Woods campground has paid off handsomely.

My class was so gung-ho that they started 45 minutes early. Since I’m a morning person, that was fine with me, but I warned them they must get adequate rest. They wanted to finish paintings they’d started on Monday before we moved on. To that end, we returned to Schoodic Point.

Schoodic Institute provides bag lunches and snacks so we can stay out all day. At 11 AM we had fresh zucchini bread and grapes and moved to a far corner of the Point, where stunted Jack Pines break up the rock slopes.

A student asked me what a Jack Pine is. “Something

Tom Thomson and the

Group of Seven painted,” I answered. I didn’t think it was a real species, just a term for a windblown boreal tree. Turns out I was wrong.

Pinus banksiana is a tree of Canada that breaks out into a few boreal forests in the northernmost United States, including at Schoodic Point.

Lynne and her Jack Pines.

I think it’s helpful to know something about the rocks and trees one is painting. Schoodic is famous for basalt dikes running through older pink granite. Granite tends to fracture horizontally; basalt fractures vertically. Both fracture in cubes that then wear down with glacial slowness. Knowing this makes our drawings more accurate.

I gave Lynne a difficult assignment: to draw the Jack Pines using color in the place of value, like the Impressionists did. She was then to integrate local color into her work without doing any blending at all. The result was pure

Tom Thomson.

Our new location among the pines was about as popular as Times Square. A stream of people continuously stopped to talk to my painters. I was debating what to do about that when my pal

Renee Lammers stopped by with a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken for us. The party was on!

“Schoodic Point,” by Corinne Avery (finished).

While Renee sold paintings and Sketch-n-Cans to the constant stream of visitors, my class painted, sketched and laughed. And then, at about 4:15, it was suddenly lights out for all of us. I tried to demo about color temperature and found myself hopelessly confused. My students felt the same way. We packed up and headed in for a rest before dinner.

Discussing drawing rocks with my students. (Photo courtesy of Susan Renee Lammers)

One only gets a certain number of clear-headed work hours in a day. We like to believe we can push past that, and we can, for a limited time. But the quality and assurance of our work declines.

At six, we had a lobster feast in the cool, fresh air, and by 7:30, we were all tucked up in our rooms. All that fresh air, sunlight and exercise had taken its toll. We hope to catch the

Perseid Meteor Shower later this week, so we can’t wear ourselves out now.