When working big, start with a smaller sketch and grid it up. It’s easy.

|

A large canvas transferred from a 9X12 sketch.

|

When you’re on the road, no two billets are the same. I was confident that I could use a tethered hotspot to write this morning’s blog, but then realized I’m in a cell-signal hole. So I’m reworking an earlier blog on aspect ratio. It’s especially important when transferring a field value sketch to your finished paper or canvas.

The largest I generally work is 60X60. This is too large to draw directly, as I can’t get far enough away to see the whole thing as I’m drawing. When I’m working this big, I always do a smaller sketch in oil or cartoon in graphite first. Then I scale it up. This prevents proportion distortion.

I have a projector, but I find that gridding is more accurate and takes less time.

I realize many artists are math-phobic, but there are times when an small bit of arithmetic can save you a lot of work. I’ll try to make this painless.

The first step is to work out whether the aspect ratio of your sketch is the same as the canvas. This is the proportional relationship between height and width. If you’re cropping a value sketch, you want to be sure that the aspect ratio of your crop is the same as will be in the finished canvas.

|

|

Usually I grid in Photoshop because it’s faster and I can just delete the lines with a keystroke. But you can grid just as well with a pencil on your sketch.

|

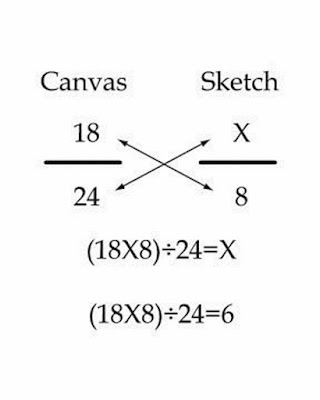

Sometimes this is very obvious, such as a 9X12 sketch being the same aspect ratio as an 18X24 canvas. But sometimes, you’re starting with a peculiar little sketch drawn on the back of an envelope. You can use a trick you learned back in elementary school.

Remember learning that 1/2 was the same as 2/4? We want to force our sketch into a similar equivalent ratio with our canvas.

Let’s assume that you’ve cropped your sketch to be 8” across. You want to know how tall your crop should be to match your canvas.

Write out the ratios of height to width as above.

To make them equivalent, you cross-multiply the two fixed numbers, and divide by the other fixed number, as below:

Use your common sense here. If it doesn’t look like they should be equal, you probably made a mistake. And you can work from a known height as easily as from a known width; it doesn’t matter if the variable is on the top or the bottom, the principle is the same.

The next step is to grid both the canvas and sketch. You could spend a lot of time calculating the distances, but I prefer to just divide it in even amounts in each direction. I use a T-square and charcoal, and I’m not crazy about the lines being perfect; I adjust constantly as I go.

The last step is to transfer the little drawing, square by square to the larger canvas. I generally do this in a dark neutral of burnt sienna and ultramarine. It’s time-consuming, but with big paintings it saves a lot of work in the long run.