Do you allow yourself to believe you’re good at what you do? If not, why not?

|

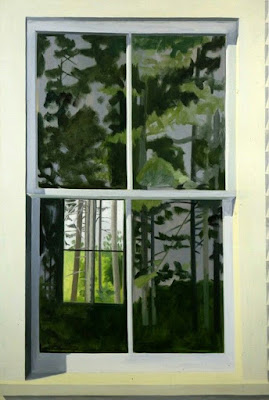

| Campbell’s Field, by Carol L. Douglas. At the time I painted this, I thought I was a pretty poor painter. |

I rudely eavesdropped on a conversation about negotiating salary. The speaker, thirty-something, was describing input from friends and family. “Dad said, ‘ask for the highest figure in their range,’ and Steve said, ‘ask for $5000 more.’” The negotiator—a woman—asked for $1500 more. She low-balled herself. At her age, I would have done worse. I’d have meekly accepted whatever was put on the table.

The gender pay gap is more complicated than simple sexism. It starts with college graduates’ first jobs. Part of this is based on the college tracks women prefer (non-STEM) but part of it is simple confidence. The responsibility for that rests with us, as women. No manager has ever insisted that a candidate take more than what was first offered.

|

| Bridle path, by Carol L. Douglas. Same vintage. |

The confidence gap is even more of a challenge in the art world, where success is based on selling oneself. Frankly, women are lousy at it. I’ve written here, here, here, here, here, and hereabout gender disparity in the art world, and it hasn’t gotten any better. The gap between men’s and women’s pay in the arts is worse than it is in the economy as a whole. That’s a clue that the gender gap is about far more than just majoring in STEM subjects.

My daughter and her husband have turned job stereotypes on their head. She’s a computer programmer; he’s a social worker. “When she knows she’s excellent at something, she’s very confident about it,” he says. That is new. As a recent college graduate, she was unsure. She allowed herself to be hired at the bottom of the pay range. She’s wised up and is working to narrow that.

|

| Upper and Middle Falls, Letchworth, by Carol L. Douglas. |

I often tell people I only know how to do two things well, and one of them is not cooking. I can paint, and I can write and teach about painting. In those narrow tracks, I’m competent. More importantly, I know it.

But I wasn’t always that way. Paintings I did twenty years ago are no less accomplished than my paintings today (albeit in a different style). Why did I feel then that I was a poseur and today I feel capable? What has changed?

In part, I was influenced by what others said about me. There are supportive communities and others that subtly undercut our self-esteem. Think back through recent interactions with your peers. Did they encourage you to take risks, or float good ideas for improvements? Or do they subtly discourage you? If the latter, perhaps you need new friends. (Family is not so easy to change, unfortunately.)

|

| Lower Falls, Letchworth, by Carol L. Douglas |

Sometimes the person who smack-talks you is not your so-called friend, it’s you, yourself. Your inner monologue has a critical impact on your confidence. Try to listen to your own commentary and analyze it dispassionately. If you find yourself constantly running yourself down, stop and redirect those thoughts.

Start by intentionally choosing a posture of thankfulness. I know of no more powerful tool to reframe our attitudes. In giving thanks, we focus on what’s right and good, rather than on what’s broken.

Women, in particular, are trained to be modest about their achievements. But there’s a fine line between humility and self-effacing meekness. Confident people take credit for their own achievements—to themselves as well as to others. As a teacher, I’ve noticed that people who were successful and confident in their careers bring that expectation of success into painting.

If you don’t have that, don’t despair. Instead, challenge yourself in some area that’s far outside your experience. Doing something risky and difficult is a great way to start to understand your own strength. The time I’ve spent alone in the wilderness has been a powerful spur to my own self-confidence. We send boys to camp to get filthy and learn to start fires without matches; we don’t send our daughters. We should.

Women are trained to be helpers and—as I mentioned before—that can be a trap. But it’s also a strength we can build on. I have found mentoring to be a great spur to my self-confidence, if for no other reason than that the people I’ve mentored admire me.

But there’s something to be said for plain old age. I think in some ways I’ve simply outlasted my insecurities. They’re exhausting, and at this age I have better things to do with my time.