The violence and inhumanity of war is apparently a lesson that every generation needs to learn for itself.

|

|

The Third of May 1808, 1814, Francisco Goya, courtesy Museo del Prado. |

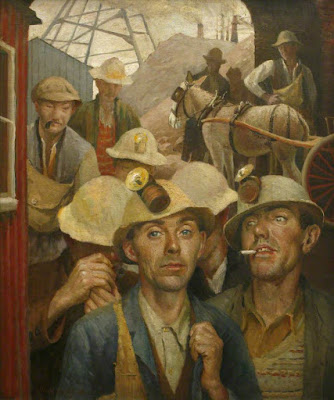

Francisco Goya was the most important Spanish artist of his day. His late painting, The Dog, was an icon for modern and symbolist painters through the 20th century. There’s a good reason: it prefigures modern art.

Goya became a court painter in 1786 and the First Court Painter to the Bourbon monarchy in 1799. This made him, in effect, a courtier of the Crown. As expressive as his painting was, he wrote nothing about current affairs.

In 1808, Napoleon turned on his former allies and occupied Spain. He forced the abdication of the King and installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne. Spaniards rejected French rule and fought a long and bloody guerrilla war to oust them.

|

|

The Third of May 1808, 1814, Francisco Goya, courtesy Museo del Prado. |

The war started with the Dos de Mayo Uprising, the reprisals to which were memorably recorded by Goya in his masterpiece above. This was painted in 1814, after the war ended. Whatever his private thoughts, Goya meant to stay alive and working.

Goya remained in Madrid through the conflict. His ruminations resulted in a series of prints called The Disasters of War. That’s a modern title; Goya’s only written comment was on a proof-set, where he wrote, “Fatal consequences of Spain’s bloody war with Bonaparte, and other emphatic caprices.” In using the word caprichos, which also translates as ‘whims’, Goya said a mouthful.

|

|

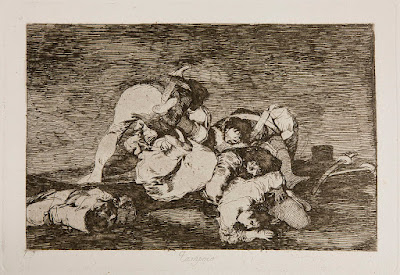

Plate 10: Tampoco (Nor do these). Spanish women being raped, Francisco Goya from The Disasters of War, courtesy Museo del Prado. |

The Disasters of War is a series of 82 prints, finished between 1810 and 1820. They are an expression of revulsion against the violence of the Peninsular War, an outpouring from the gut against the inhumanity of war. There is no polemic about the causes of the conflict, despite the fact that Goya retained his position in the Bourbon court while working on them. They were private works, and not published until 35 years after his death. Their influence has been incalculable.

Fast forward to 2003 and a pair of British art enfants terrible, Jake and Dinos Chapman. They purchased a folio of the Disasters of Warand set about systematically defacing it with cartoon figures drawn over Goya’s art. They called this appropriation work, Insult to Injury and the overall show Rape of Creativity.

|

| One image of Jake and Dinos Chapman’s defacing of Disasters of War, which they retitled, What is this hubbub? |

“Drawings of mutant Ronald McDonalds, a bronze sculpture of a painting showing a sad-faced Hitler in clown make-up and a major installation featuring a knackered old caravan and fake dog turds,” is how the BBC described the show at the time.

For this twitting of human suffering, they should have been spanked and sent to their rooms. Instead, they were nominated for the Turner Prize.

The Chapmans were born in the 1960s. They have lived through the longest period of peace in modern British history. The Disasters of Warmight have seemed funny to them, but it would not have amused those who remembered the convulsions of the two great 20th century European wars.

That kind of generational amnesia is an odd function of the human mind. It’s the only possible explanation for why we get into war over and over again.

I hadn’t meant to write on this subject, but the war in Ukraine couldn’t have happened without the slow forgetting of the violence and inhumanity that is war. Apparently, it’s a lesson that every generation needs to learn for itself.

.jpg)