Who painted these lovely, overlooked murals in Rockland ME?

| Mural at Ocean State Job Lot, Rockland, ME. |

Inside the lobby at Rockland’s Ocean State Job Lot—in the northwest corner where they put promoted seasonal merchandise—is a set of murals. There are more in the breakroom, where we never go. These were painted more than 25 years ago, when the building was a Wal-Mart. To Ocean State’s credit, they’ve never been painted over, but they are badly in need of restoration. The fluorescent lighting in the store is pretty awful.

| Mural at Ocean State Job Lot, Rockland, ME. |

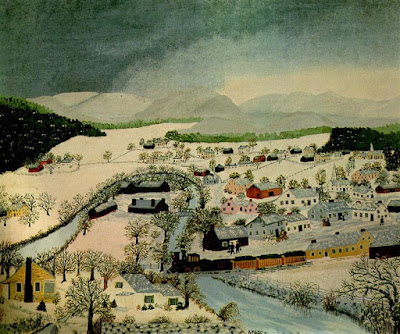

The murals are an utterly charming look at Rockport and Camden and their fine flurry of sailing vessels. The American Boat Yard sheds are still standing below Mount Battie. An amazing potpourri of wonderful vessels bobs around the light at Rockland, including schooner Victory Chimes and the US Coast Guard Cutter Thunder Bay. The lobster smack Joseph Pike is tied up at its dock.

At first you think the boats were transcribed from photos, but then you take a good look at them and realize that nothing in these murals are real. Rather, they’re fantastical, as if in a dream. Camden has fewer houses than it would have in a 19th century painting by Fitz Henry Lane.

| Mural at Ocean State Job Lot, Rockland, ME. |

One of the pieces has a clear signature: Ed L. Roberts ’92. An Ocean State employee thought he was someone who worked at the store. A cursory Google search tells me nothing. So, sadly, I know nothing of their provenance. Rather, I’m asking you: who painted these and when? If you have any idea, please comment below.

| Mural at Ocean State Job Lot, Rockland, ME. |

If you’re visiting Rockland, Ocean State Job Lot is probably not on your bucket list. Still, you might want to stop and take a quick gander at this amazing folk art. If you think of it, thank the manager for not painting over them. They’re a charming part of our local history.