When drawing and painting these trees, notice the branch placement, the whorls, the broken spots, the needle color.

|

| Black spruce (courtesy of Wikipedia). |

If you’ve read this blog for a while, you know that I periodically introduce you to a green matrix, by which you can defeat the ‘wall of green’ that overwhelms us every year at the end of June. That’s when trees and grasses assume their mature foliage. As elegant as nature is, you’re not going to make a compelling painting of them by squeezing puddles of chromium oxide, veridian, and sap green out of their tubes and smearing them everywhere on your canvas.

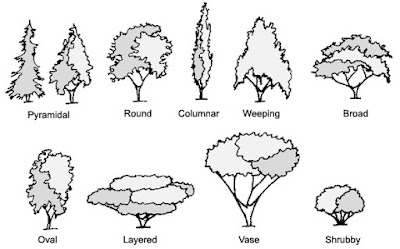

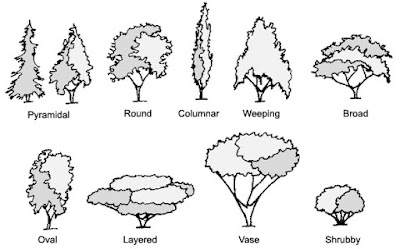

It helps to start by knowing your trees. Even this early in summer, there are differences in the canopy shape that help to define the tree canopy. This is a place where careful drawing is important.

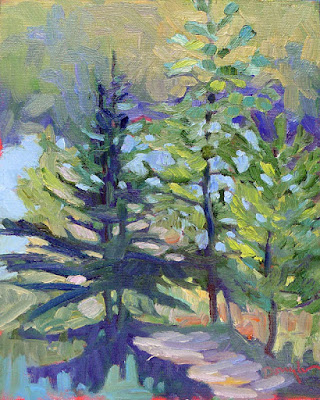

Our evergreens deserve thought as well, especially if you’re painting along the coast. When drawing and painting these trees, take your time. Notice the branch placement, the whorls, the broken spots from weather. Mix the needle color carefully.

Last week in class, a student was debating the color of the black spruces in the far distance. I suggested he mix them using black. “It is, after all, its name,” I said. That’s not coincidence; that common name comes from the darkness of its foliage in certain situations.

Black spruce is so widespread in Canada that it ought to be the country’s official plant. We have it in Maine (and in the Adirondacks, Minnesota and Michigan) because we’re an extension of the boreal forest of the Great White North.

Black spruce is a slow-growing, scruffy conifer with a narrow, pointed crown. That scruffiness is exaggerated when it’s growing on the coast, buffeted by weather. But that’s also why black spruces are survivors on lonely promontories; they’re adapted to miserable weather. In fact, that’s the common trait of all our northern evergreen species.

(By the way, if you can’t tell the difference between a black and a red spruce, don’t worry. Neither can they. They hybridize here where their ranges meet.)

|

| Eastern White Pine (courtesy of Wikipedia) |

Eastern white pine is, of course, the official state tree of Maine. The massive masts on the windjammers you see off shore are most likely white pine, since the tree can reach 135’ tall in the wild. White pine is an important lumber tree and a superstar food host for wildlife, including black bears, rabbits, red squirrels and many birds. While the tree may not like it, its bark is an important food source for beavers, snowshoe hares, porcupines, rabbits and mice.

White pines are identifiable by their needles, which are clustered in groups of five. They’re so common here that if you see a pine tree with a blueish green cast to the needles, you can just assume it’s a white pine. It’s got a far nicer habit than the black spruce, growing in a pyramidal shape. Of course, as it gets older and ravaged by time, that shape gets broken up. Just as with us humans.

|

| Jack Pine (courtesy of Wikipedia) |

I used to think that Jack Pine was a descriptor of a shaggy, wind-swept tree, rather than a species name. It wasn’t until I saw them growing at Schoodic that I realized they were, in fact, a species in their own right. They’re common enough in Canada, and they grow in pockets here in Maine.

Jack pines seem to pick out the worst rocky or sandy soil on which to make their stand. They’re even more scruffy than black spruces, often bent into the wind.

|

| Balsam fir foliage (courtesy of Wikipedia) |

The woods here are also home to balsam fir, which are a small-to-medium fir with a strong pine scent. They’re iconic Christmas-tree beauties, with short, flat, glossy needles and a beautiful habit. They’ve got no great commercial value as lumber, but they’ve been awfully handy to humans as a source of medicine. Many creatures eat their foliage and seeds or seek shelter beneath their boughs.

Although evergreens don’t lose their needles in winter, it’s wrong to think that they don’t change color. They have periods of growth where the green is fresh, and times when they’re dormant. They change color, but the changes are subtle.