Avoiding black keeps you from some of the most elegant colors available in painting.

|

| Vineyard, 30X40, oil on canvas, available. Black can make a whole array of beautiful greens. |

One of the absurdities of 20th century art education was the injunction to ‘never use black.’ That limits artists from some of the most elegant colors available in painting. The argument is supposedly based on Claude Monet’s palette; he never used black and you shouldn’t either. Like the so-called Zorn Palette, that’s a stew of half-truth and myth. Most artists’ palettes shift over time.

Asked in 1905 what colors he used, Monet said: “The point is to know how to use the colors, the choice of which is, when all’s said and done, a matter of habit. Anyway, I use flake white, cadmium yellow, vermilion, deep madder, cobalt blue, emerald green, and that’s all.” But earlier in his career, he certainly used a wider palette, including black.

|

| The Servant, 36X40, available. Black is invaluable in creating skin tones. |

The argument went that Impressionists avoided black because it doesn’t exist in nature. Black certainly does exist in nature: in basalt, in deep shadows, and in the subtle undertones in animals and people.

Moreover, it was argued, the painterly effects created by managing warm and cool hues are richer and brighter than those created by manipulating tones and shades. They’re more brilliant, certainly, because adding black (or white) always reduces chroma. But part of painting is the dance between high chroma and neutrals.

Anyway, Monet’s buddy and fellow founder of Impressionism Édouard Manet used black paint by the bucketful.

Monet said a mouthful in that quote, however, and it wasn’t the list of colors (most of which would not be great choices in the 21stcentury). Most of us choose paint colors purely out of habit. We become familiar with them and develop deep loyalty to them. That’s smart, as long as we choose wisely to start with.

But then the painter often gets into the bad habit of only mixing colors in a certain way. And that, in the tail end of the 20thcentury, meant never using black.

Obviously, you should never make grey by mixing black and white, because it’s lifeless. But there are many subtle colors available only through black admixture.

|

| Black admixture chart of my palette. You should make one too. |

In painting:

- Tint is a mixture of a color with white;

- Tone is a mixture of a pigment with grey (black plus white);

- Shade is a mixture of a pigment with black.

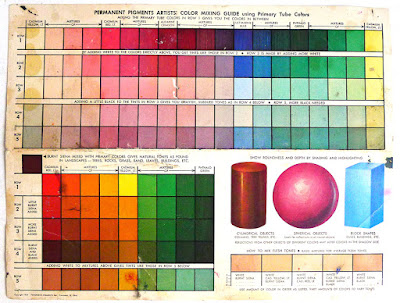

What we consider acceptable in color-mixing is style-driven, just like everything else. For example, see the Permanent Pigments Practical Color Mixing Guide of 1954, below. It’s all about making shades and tints. That’s a hint about why mid-century paintings looked so grey, and probably why the pendulum then swung so far in the other direction. A little shading goes a long way.

|

| Yes, it’s a mess. It’s been kicking around various paint boxes in my family since 1954. |

This product was a response to market demand. It’s very hard to paint without some black on your palette, and the real stuff was banned by the cognoscenti. But when I was in school (she says with a geriatric cackle) chromatic black was something we were taught to mix. That’s a valuable exercise in complements. Buying it premixed in a tube circumvents the point.