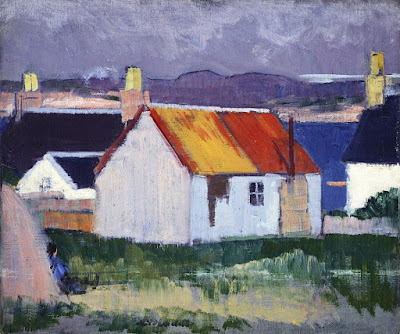

Mary, Queen of Scots by Jacob de Wet II, from the Great Gallery at Holyrood Palace.

Edinburgh’s

Palace of Holyroodhouse is apparently where the Queen stores the motley family geegaws that don’t fit in her other palaces. There is one room that should be of interest to art aficionados, however—the Great Gallery, which originally served as the Palace’s privy gallery and is still used for state occasions. Its decorating scheme revolves around a monumental series of portraits of the Scottish monarchs, beginning with the legendary

Fergus I (who is said to have ruled Scotland from 330 BC) and ending with

Charles II.

This series of paintings was intended to endorse the ancient, venerable and divinely-appointed line of the Stuarts. It told the viewer that their rule would ensure peace and prosperity for Scotland. It was done as part of Charles’ extensive restoration of the Palace after it was burned by Cromwell’s soldiers in 1650.

The portraits were done by Dutch Golden Age painter

Jacob de Wet II in an act of unrivalled hard work. There is nothing incisive or unique about them, nor could there be: he churned 110 of them out at the rate of one every two weeks, working non-stop on the project from 1684 to 1686.

The Scottish king Dorna Dilla, by Jacob de Wet II, from the Great Gallery at Holyrood Palace.

Charles II was de Wet’s principal patron. The king never saw the work; after his Scottish coronation in 1651, His Royal Highness hightailed it south and stayed there. De Wet’s portrait of Charles II was done from other likenesses. In fact, Holyrood Palace never commissioned a state portrait from any of the great painters of the day, and certainly not from either of the two great

Principle Painters in Ordinary to the King,

Sir Peter Lely and

Sir Godfrey Kneller. That tells us exactly where Holyrood and Edinburgh ranked in the politics of the day.

Back to humble Jacob de Wet, then. He was first hired in 1673 by Sir William Bruce, the King’s Surveyor and Master of Works in Scotland. De Wet produced a series of classical history paintings for the newly-rebuilt state apartments at Holyrood. Many of these paintings remain. After this, he remained in Scotland, doing commercial work for the great and mighty.

Most of Jacob de Wet’s paintings in situ, courtesy of Susan Abernethy.

In 1684 de Wet returned to Holyrood. His contract with the Royal Cashkeeper reads: “The said James de Witte binds and obleidges him to compleately draw, finish, and perfyte The Pictures of the haill Kings who have Reigned over this Kingdome of Scotland, from King Fergus the first King, TO KING CHARLES THE SECOND, OUR GRACIOUS SOVERAIGNE who now Reignes Inclusive, being all in number One hundred and ten.”

Today 97 of the final 111 portraits are on display in the Great Gallery. They were loosely based on a series of 109 Scottish kings painted by

George Jamesone in honor of Charles I’s Scottish coronation in 1633. Such of Jameson’s work as survived civil war were sent to Holyrood for de Wet to copy. De Wet relied on these, on

George Buchanan’s list of Scottish kings, and on other source material. If he used any models at all, they were completely interchangeable, for there is nothing characteristic about those ancient faces.

The scale of de Wet’s achievement is unique. While he may never be remembered for his delicacy of brushwork or incisive understanding of character, he deserves recognition for having finished at all.

On leaving Holyrood, I remarked that, were I forced to live there, I’d abdicate. The weight of those ancient stones is not romantic to me; it’s oppressive. Apparently, I’m not the only person who sees historic privilege as a burden, as this

sad obituary states.

I intended to post regularly from Scotland, but the internet defeated me. My mobile’s problem I sort of get; it’s elderly (all of two years). My laptop generally travels well. Its refusal to acknowledge wifi at our destinations was baffling.

Nonetheless, I’m home and working this morning after that new tradition of modern air travel: the short hop that becomes a 24-hour dance contest.

We flew with a Canadian carrier just to avoid this, and they were, in all things, far kinder than their American cousins in similar circumstances. A delay in Edinburgh caused a missed connection in Toronto that in turn revealed our luggage to have strayed, resulting in an additional delay in Montreal for Customs declarations. This meant we left the airport at rush hour, which in turn meant a climb over Grafton Notch at night when the wee sleekit moose were in motion. We left our flat in Edinburgh at 6 AM GMT and arrived at home at 1 AM EST, meaning 24 hours of travel. If I don’t make sense, that’s why.