The only thing you can predict with certainty about this summer’s weather is that it will rain.

| Just slightly soaked, I try again. Photo courtesy of Annette Koziel |

Fishermen’s Memorial Park sits above the lobster fleet in Boothbay Harbor. It’s a sobering memorial; the list of lives lost at sea is long and a fresh wreath hangs on its bronze dory. Behind the park rises the uncompromising white frame spire of Our Lady Queen of Peace Catholic Church, celebrating its centenary this year. Its vaulted ceiling is reminiscent of the ribs of the Ernestina-Morrisey, currently laid open in Boothbay’s shipyard. On the hour, Our Lady’s carillon peals earnest hymns across the water.

|

| Our Lady of Peace Catholic Church. |

Bobbi Heath, Ed Buonvecchio and I were meeting to demo for Windjammer Days. We’d planned to grab lunch in town and then paint at the Fire Hall, where a tent was set up for our convenience. However, we’re landscape painters. The best view of all was from the park and the church.

Clearly, everyone else thought so too. The place was mobbed. Late in the morning, one of my students, Jennifer Johnson, stopped by. We were just coming to grips with the idea that we couldn’t leave to get something to eat. Jennifer kindly volunteered to fetch our lunches. The restaurant was closed, so she brought us fresh vegetarian chili made with her own two hands. That, friends, is ‘supporting the arts.’

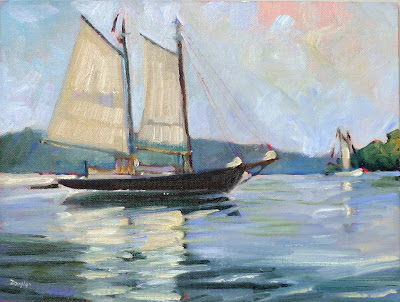

| American Eagle, a tug, and an antique launch… clearly the best view in town. |

“It’s going to be a great day,” Jennifer promised me. “No rain on the forecast.” Radar agreed with her. Large fluffy clouds marched in from the west. Our displays of work were set up, we were surrounded by interested people asking intelligent questions, and below us paraded a motley collection of fantastic winged angels, the windjammers for which the festival is named.

A young lad named Ben positioned himself next to me, trying to name the boats as they came in. “It’s just like identifying cars,” I told him. “You figure out the model from its shape and its details. Does it have a topsail? A bowsprit? A racing stripe?”

| My sketch. The tide was on the turn, so the boats were swinging. |

He was fascinated by the privateer Lynx. It’s an interpretation of an historic privateer built in 1812 to run British naval blockades. Its masts are severely raked, meaning they tilt. This term gives us the modern word rakish.

The boats and their adoring fans moved on. Ropy fingers of moisture started to spill down from the friendly cumulus clouds. “It’s raining there, there, and there,” I said to Ed and Bobbi. We’d barely repacked our gallery when the skies let loose.

| Rain, again. |

Annette Koziel, a friend and fan from Brunswick, arrived with the rain. She had a tarp in her car. We tossed it over my easel and ran for Bobbi’s car. Artists know that if Nature throws a passing shower, you use the break to find a bathroom.

|

| At the Lobster Dock. |

It stopped as quickly as it started. I mopped up and tried again. I picked up my brush and a second shower poured down. I can take a hint, I thought.

| Lobster boats at Boothbay (unfinished) by Carol L. Douglas |

I had an errand to run in Brunswick, so I headed south, taking me across the giant parking lot that is the Wiscasset bridge. Generally, I do sums in my head when I need to stay alert while driving, but Annette gave me a great tip. A small radio station broadcasts quirky, mid-century standards from an old tidal mill in West Bath. If you’re traveling up Route 1, try tuning your radio to 98.3.

Later, I heard from Jennifer. She was so sure it wouldn’t rain that she left her windows open while she ran in the grocery store. Now, that’s adventurous.