There’s no shame in painting what people love, as long as you do it well.

|

|

Two chattering housewives, 1655, Nicolaes Maes, courtesy Dordrechts Museum

|

If I weren’t in Buffalo, I could fly to see Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age, opening on February 22 at the National Gallery in London. (London and Los Angeles are roughly equidistant from my house, so that’s not as daft as it seems.)

The Dutch Golden Age (the 17th century, roughly) was when trade brought prosperity to the Netherlands. That, in turn, fostered a flowering of scientific thought, military might and culture. The conditions that made this possible were the nation’s recent liberation from Spanish rule, a solid Protestant work ethic, and the development of a new kind of business: the corporation.

The Dutch East India Company was founded in 1602. It was the first multinational corporation and it was created by exchanging shares on the first modern stock exchange. This may seem humdrum to us, but at a time when for most of the world wealth and poverty were inherited conditions, it allowed for the creation of thriving merchant and middle classes.

|

|

The Eavesdropper, 1657, Nicolaes Maes, courtesy Dordrechts Museum

|

Until the Dutch Golden Age, great art was commissioned by extremely wealthy people, who essentially dictated the tastes of the times. Suddenly, middle class people were buying art. This radically changed what artists painted.

The Dutch Reformed church and Dutch nationalism informed the aesthetic of Golden Age painting. Catholic Baroque was out; simplicity and Calvinist austerity were in. Dutch art concentrated on reality and ordinary life at all levels of society. The focus on realism is why the period is sometimes called Dutch Realism.

Always that realism was invested with meaning. Significant in this worldview was a rapid growth in landscape painting, particularly as it represented unique Dutch values and scenes. A windmill on a flat plain or a boat at sea may seem like tropes today, but they were symbols of heroism to the audience of the time.

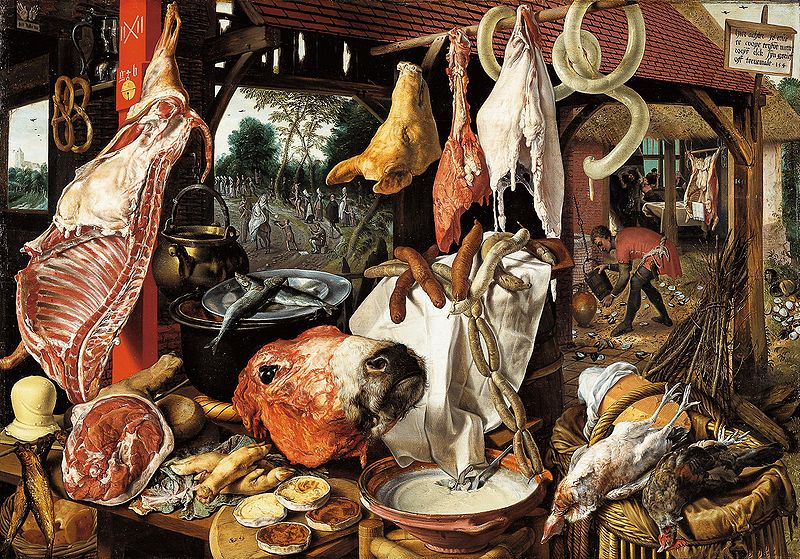

The Dutch painted lavish still lives that seem overly full and overripe to modern eyes. They were simultaneously objects of beauty, symbols of abundance, and full of symbolic meaning. Among these are floral vanitas paintings, done with scientific accuracy while warning us of our ultimate destiny.

|

|

The Virtuous Woman, c. 1656, Nicolaes Maes, courtesy Wallace Collection

|

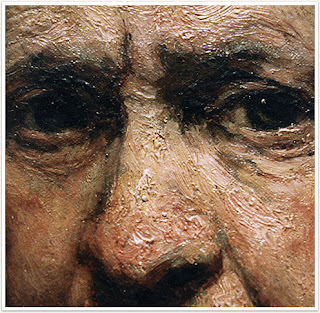

Genre painting underwent a renaissance, because home and hearth were as important to these middle-class buyers as they were irrelevant to princes elsewhere. Nicolaes Maes was among the most important of these genre painters. After studying with Rembrandt for five years, he hung out his shingle, first in Dordrecht and then in Amsterdam. Like so many artists, he didn’t specialize in the beginning, painting whatever was necessary to make a living. After about 1660 he focused on lucrative portrait paintings. It was a good strategy, because he died a very wealthy man.

The contemporary American artist has two broad market paths open to him. The first is to produce conceptual art that is meaningful to high-flyers in New York. The second is to produce work that appeals to middle-class buyers. If the latter is your target audience you can learn a lot by studying the careers and subjects of Maes and his peers.

There are those who sneer at plein air painting even as it develops into the largest modern movement in painting. But the critical message of the Dutch Golden Age is that there’s no shame in painting what people love, as long as you do it well.