I’m willing to look like a fool for art. Are you?

| Channel marker, 9×12, oil on canvasboard, $696 unframed. |

I did a set of long demos in my classes this week. I worked from two different snapshots, one for each class. I’d never looked at them before. In fact, I chose them because they didn’t have any obvious structure.

It was up to my class to create that structure, so I didn’t crop or make any choices in advance. (To make the demo meaningful to all my students, I did each painting in oils and watercolor simultaneously. That’s hard.) The goal was to give my students a broad view of the overall processes of painting, from start to finish.

They said they learned the most from the many places where I dithered. At one point, I said something like, “stupid, stupid, stupid!” One student particularly liked hearing that; she thought she was alone in making choices she later regretted.

|

| Fog Bank, 14×18, oil on canvasboard, $1275 unframed. |

Another said that the most instructive part of the demo was the moment I took a rag to an entire passage of the oil painting. (My correction turned out to be a mistake. Stupid, stupid, stupid.)

The actual painting results were mediocre. But great paintings were never my goal. Instead, we worked our way through the process of a painting as a team, discussing our questions and dilemmas.

|

| Home farm 2, oil on canvas, 20X24, $2898 framed. |

I received this email from a student who wishes to remain anonymous:

“A couple of weeks ago, on a whim, I signed up for another zoom painting class with an artist I follow on social media… The most important thing I have come to realize is how much I value your approach to teaching and how much better your class is. I enjoy your [art] history lesson and how it wraps around the weekly lesson. We all work from our own still life set-ups or reference photos making our paintings more personal.

“In this other class, I was sent a reference photo (which didn’t particularly interest me) and we all painted the same thing. During class, there is a lot of talk about which particular colors were used in which particular spots. Questions like these make me nuts.

“We have to send a photo of our painting and there is a critique of everyone’s work so we are looking at basically eight versions of the same painting for two hours. Tedious, at best. In the end, I feel like I have spent time and materials on a painting that is not really mine since I don’t own the reference photo and I know there are eight other versions of the same painting out there.”

|

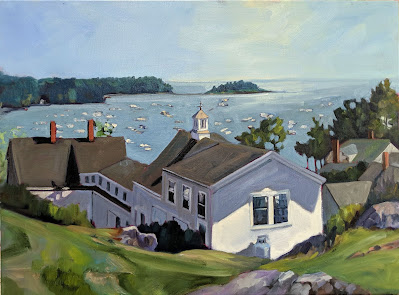

| Home Port, oil on canvas, 18X24, $2318 framed. |

This student is a graphic designer by trade, so when I saw her painting, I was amazed at how boring it was. Her work usually sparks with arresting design and quirky ideas. But here she was working from someone else’s idea, and all the thinking was already done. There’s little to be learned in that.

On Monday, I wrote that I don’t think canned painting demos are very helpful. A shrewd painter rehearses these performances. He has already made the critical decisions before he ever lifts a brush in public. This creates an impression of mastery and confidence, but it’s a falsehood. The real process of painting is all in the choices.

Art’s greatest enemy is safety. That may seem strange coming from a painter who works in landscape—surely the least risky of genres. But the risks I’m talking about are in composition, structure, color choices, and brushwork, not in content. The best painters take chances all the time. They mess things up and toss them in the trash. The public will only see 10-20% of our starts. The rest are, to us, failures.