If you’ve learned to do one thing well, you can apply that technique to anything else you want to do.

|

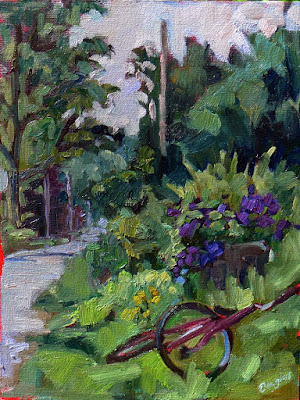

| Abstraction, by Carol L. Douglas. My hair looks a lot like this. |

Those who know me will be surprised to learn that I occasionally brush my hair. I like it long, but it has more than a little ‘fro in it, which makes it hard to maintain. Earlier this year I went to a new hairdresser. Kim spent a great deal of time teaching me how to shape my hair without a hairdryer. When she was done, I looked smashing—until the next day, when it was back to its usual, out-of-control, self.

My first reaction was to just let it go, even though I hate it looking like a bottle brush. “But wait,” I thought. “If Kim could make this work, it means it’s possible. She showed me how; what I have to do is practice.” And so, I practiced. And while I’m still not as good at it as she is, somedays it doesn’t look half bad.

|

| My friend Jane, by Carol L. Douglas. She’s taught me a lot of things over the years. |

I see a physical therapist twice a week to work on my back. She’s very young, and she’s very tough. Every visit, she adds something new, kinky (in the pretzel sense) and too complex for me. “Now, remember to breathe,” she admonishes after she’s just given me eighteen other orders. I can’t seem to activate my back, contort my extremities, and draw air all at the same time. Every week, I leave feeling confused.

Yet I go home and try again, because I promised her that I’d practice three times a week. The first time is always awkward and messy. By the time I go back to my next appointment, though, I’ve got it more or less mastered. Three months ago, Krista told me, “Age is just a number.” I laughed; she’s my youngest daughter’s age. Now I’m starting to believe her. The improvement has been life-changing.

|

| Listening in church, by Carol L. Douglas. Part of learning to paint is incessant drawing. |

By the time we’re adults, we’ve all pretty well mastered something— Crêpes Suzette, tax preparation, Greek diacritics, Morris dancing… the list is as infinite and varied as humans ourselves. Here are some things I’ve mastered:

- Making pies;

- Cleaning;

- Numerical computations in my head;

- Driving;

- Folding laundry.

What about you? What are you good at?

For most people, it’s easier to enumerate our shortcomings than our successes, but that’s a mistake, as I

wrote here. I certainly have things I’m not good at, starting with cookery. But I’m a bad cook because I have absolutely no interest in food.

That’s the first difference between success and failure: we succeed at what we love; we fail at what we dislike. “You could do it if you just tried,” I heard as a kid, and now I know it was true. Our failures represent disinterest far more than incompetence.

|

| Bailiff in County Court, by Carol L. Douglas. Draw, draw, everywhere, even in court. |

Thinking about our masteries is not a feel-good exercise; it’s an invitation to look at our learning process and figure out how it worked. I made my first pies in 4H. I found better recipes and techniques, other bakers gave me tips, and I’m still looking for ways to up my game.

It’s exactly the same with more complex activities like art, music and higher mathematics. Your successes determine the method you’ll use to keep developing. Other masteries not only tell you that you have the intellectual tools necessary to take on the challenge, but that you have a method of learning that works.

Notice that I’ve not said a word about

talent here. It’s the most overrated quality in success.

Thomas Edison was entirely right when he said, “Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.” Now get to work!