We think of it as a political problem but every single coronavirus death in America is, first and foremost, a personal tragedy.

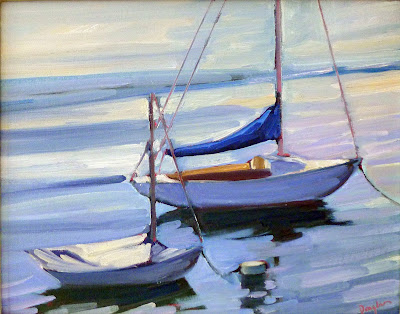

| My late Aunt Mary, painted a long time ago by me. |

I’m in Buffalo for a memorial service. My uncle was in fine fettle when I was in Argentina in March, texting me about my trip. A few days later, he was dead. Yes, I’m aware that he had lived a rich, full life, but that is small consolation for the sudden loss of someone I loved very much.

My cousins endured their father’s death in the worst parts of the epidemic, separated and unable to comfort him or each other. They’re no strangers to loss; their mother (my aunt Mary) died the day before her sixtieth birthday. I am comforted by the idea that my aunt and uncle are reunited now, along with the infant son they lost so many years ago.

Like my whole extended family, my uncle was a committed Catholic Democrat. I’m sure he was puzzled when I ended up a born-again Reagan Republican. But that was never a factor in our relationship. It puzzles me when people use politics or religion as an excuse to fight with their families.

|

| Grain Elevators, Buffalo, by Carol L. Douglas. The waterfront in my hometown looks so much better than when I painted this. I really should teach a workshop there sometime soon. |

A friend sends me videos every day criticizing our government’s response to coronavirus. I delete them without responding. The last emperor to be criticized for his response to plague was Pharaoh, and that was by his escaped Hebrew slaves; his subjects certainly didn’t mention it. Was the Emperor Justinian castigated for allowing bubonic plague into Europe, or Edward III deposed because he didn’t prevent the Black Death?

Mankind’s historic understanding has been that there are only two possible tools against plagues: prayer and science. The Ghost Map is an excellent read about the origins of epidemiology. In 1854, people were more interested in containing cholera than blaming their political opponents for its rise.

| First ward, Buffalo, oil with cold-wax medium on gessoed paper, by Carol L. Douglas |

Still, there are questions that require communal response. What we do with kids in a few weeks’ time, when they’re supposed to return to their classrooms? How do we protect our elderly? Perhaps both of these questions really point up that we have gotten a little too reliant on large institutions.

None of my kids were born in Buffalo, but they are all traveling back to pay their respects to a man I loved. I’m very touched by this. Last night I went for a walk with my oldest grandchild. He may be only five, but he has insights into complex concepts. If he never spends another day in a classroom, he’ll be fine. Both parents are engineers and quite able to teach him all the way up through multivariable calculus.

When my mother started kindergarten, she did not speak English. Her own mother was illiterate. Public school was a lifeline and the way out of poverty for my mother and her siblings. The same is true of my goddaughter, whose parents are Chinese-speaking former refugees. We have record-high levels of immigrants in the US today. They need public school. The same is true of native-born kids whose parents didn’t have good educations. We must find ways to teach them.

I’ve watched many small businesses close this year. Many of them were already struggling. Lockdown was the coup de grace that brought them down. This is economic pruning. It may yet prove to be a healthy thing for our economy, just as the Black Death ultimately resulted in the end of serfdom in Europe. I remind myself of that every day. Crisis is opportunity. Either we adapt, or we retire from the field.

But all of that is political. Every single coronavirus death in America is, first and foremost, a personal tragedy. This weekend, I’ll be thinking of my uncle and what a fine man he was, and how immeasurable a loss his death is to me, and to a whole community.