Until you start playing and experimenting, you won’t really own your own color pathway.

Bobbi Heath once posited to me that painters learn to manage color in three phases:

- They make everything grey;

- They vastly overshoot the chroma;

- They finally learn a pleasing color sensibility.

“Is it even possible to overshoot the chroma?” I riposted, because I’m apparently stuck in the second phase. I was joking, of course. In being a high-chroma painter, I’m operating within my own time and place in history. High chroma is part of our current landscape painting style.

|

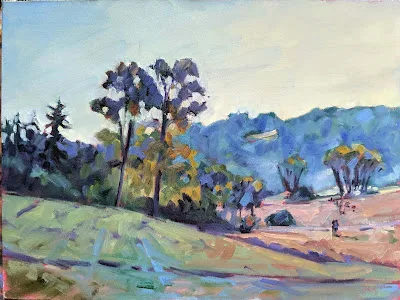

|

Beautiful Dream, 12X16, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

(For those of you new to the discussion, chroma is one of three aspects of color, which you can read about here. It means how intense the color is. Grey is low-chroma; fuchsia is high-chroma.)

Bobbi had it right, of course. Painters start in a world of soft greys because grey is safe. They need to blow through that safety net to master all aspects of color.

The problem is exacerbated when the painter lives in an area with grey skies. I spent 21 years in Rochester, NY, where the weather is controlled by tempestuous Lake Ontario. Those damp, overcast skies were great for gardening and my skin, but they mean indirect light. That, in turn, can lead to gloomier color and less separation between lights and darks. Beautiful, but dull in a painting—unless you take a page from the Luministplaybook and straight-up lie. Before you can do that, you have to be able to see it.

Giving birth to a brighter color palette can be painful. Brilliant color looks garish at first, often because our first experiments at high-chroma painting are garish. The question of color harmony is more important when our painting isn’t subdued by a leavening wash of grey. With chroma elevated, we can no longer ignore when color combinations don’t work.

|

You can’t get to that phase of development until you let go of the crutch of neutrality. This is one area where a teacher or mentor can be a great help. “Leave it,” we say. “Set it aside and look at it again in two weeks.” Actually, it would be more helpful to set it aside and paint twenty or thirty paintings in this new high-chroma space until you start to see how it hangs together.

Yes, you’ll make some awful paintings. It’s a necessary phase of growth. “No mistakes, no success. Know mistakes, know success,” my buddy Ivan Ramostold me yesterday. That’s never truer than with color. I can lecture all year about color interaction but there are millions of ways to lay colors down next to each other. Until you start playing and experimenting, you won’t really own your own color pathway.

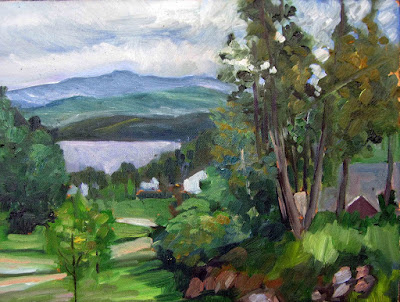

|

|

Quebec Brook, 12X16, oil on archival canvasboard, available. |

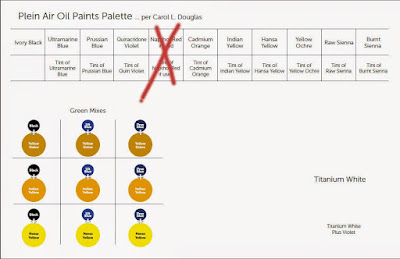

I encourage my students to have tintson their palette because they help keep color clean. These premixes can save a lot of time and prevent a whole lot of dullness.

None of this is to say there isn’t room for neutrals in painting. Of course, there is, and the third phase of color management is to add those neutrals back in. (I’m still waiting.) But let’s not jump the gun here; neutrals are in some ways the apotheosis of color, a counterpoint to chroma. They come last in our color-sensibility development.