What do we really know about traditional Chinese art? It could inform our painting in exciting ways.

|

|

Lotus Flowers, After Zhang Lu, c. 1701, courtesy the British Museum.

|

Until the Jesuits arrived in China at the end of the 16th century, western and eastern art traditions operated independently. Europeans prized certain of the minor arts—porcelain and silk—but had no interest in Chinese painting. In the 20th century, the influence ran mostly west-to-east. Only in the last few decades has the traffic reversed.

Chinese painting principles rest on the philosophical tradition of

Taoism. The Tao is an intuitive, experiential understanding of life. It emphasizes the weak over the strong, the feminine over the masculine, the water that wears down the rock, the space between things rather than the things themselves.

Taoism advocates “attaining the limit of empty space, retaining extreme stillness,” wrote the ancient Chinese philosopher

Laozi. Space is the “fasting of the heart,” wrote

Master Zhuang. Empty space is, in Taoism, “the beginning of the myriad things.” That makes it foundational.

|

|

A hanging scroll painted by Ma Lin on or before 1246. Ink and color on silk, courtesy National Palace Museum, Beijing.

|

Traditional Chinese painting treated empty space as solid space. “Knowing the white, retaining the black, it is the form of the world,” wrote Laozi. White in Chinese painting signifies emptiness. Black means solidity. In Chinese calligraphy, empty space is called ‘designing the white’.

In Chinese art, empty space is expected to convey information through its very lack of imagery. The sizes and contours of the empty shapes create rhythm and unity. The solid shapes give meaning to the empty, and vice-versa.

Those empty spaces often represent cloud, mist, sky, water or smoke, depending on the cues in the solid forms surrounding them. Of course, those so-called empty spaces are full of life and action in real life as well. Chinese painting acknowledges this. That energy in the emptiness is called qi.

|

|

Loquats and Mountain Bird, Chinese painting, album leaf, colors on silk, courtesy National Palace Museum, Beijing.

|

Whenever I see disparate cultures reaching the same conclusion, I’m inclined to think it’s a soul tie of the deepest order. It’s interesting to ponder the relationship between qi and the Hebrew נִשְׁמַת חַיִּים (nishmat chayyim) or רוּחַ (ruach).

Without qi, empty space is the same as blank space. Qi is the principle of life in painting. If it’s not there, a painting will be lifeless. Qi comes from the artist’s soul. It is a result of the interaction between the artist and the object he or she is painting. When qi is still, a painting is tranquil; when qi moves, a painting is lively.

The 20th century murdered much of this tradition. Since the Chinese cultural revolution, artists have worked around Mao’s dictum that “art should serve the masses.” Traditional forms and ideas were out; artists were persecuted and suppressed. Chinese philosophies were replaced by one-size-fits-all Communism. And Chinese painting dropped its historic roots and adopted western realism.

In western art, empty space has a place in the canon of graphic design, but not in painting. “Painting the void” in 20thcentury western painting was about destruction, not about emptiness. We are a people of loud bangs, not silence.

One exception to this was the abstract expressionist

Ad Reinhart, who took the time to study Chinese concepts in painting. I think I will join him, in my desultory way. There’s much to be learned about the power of emptiness.

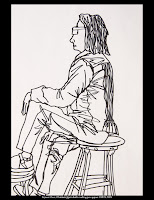

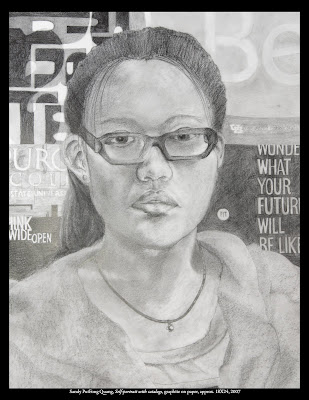

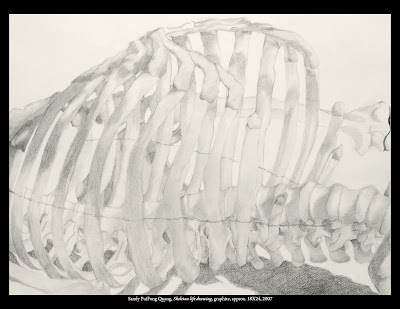

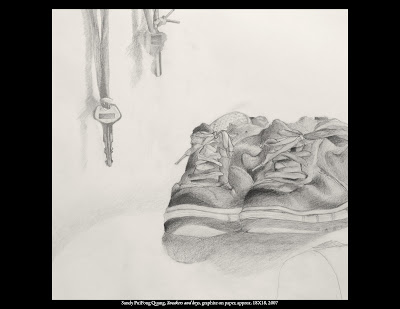

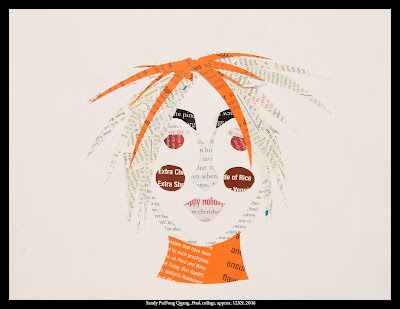

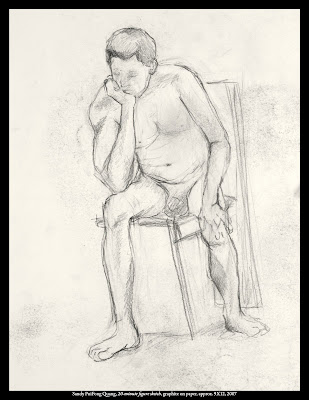

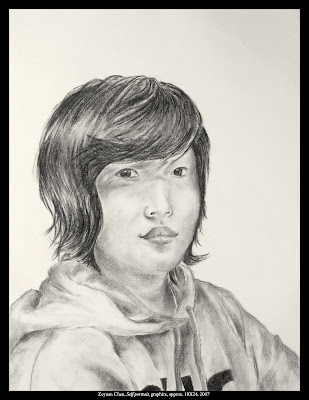

Self-portrait, graphite, approx. 18X24, 2007

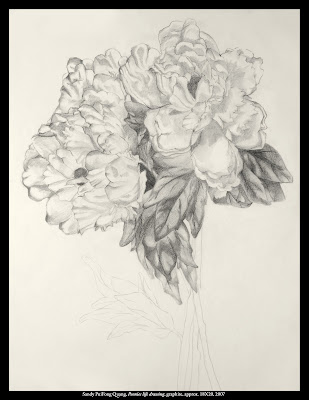

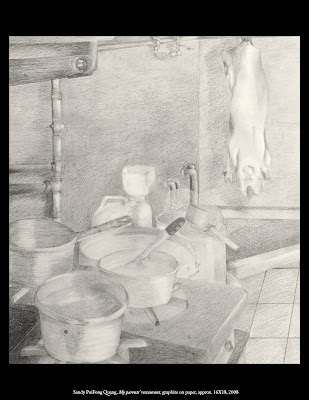

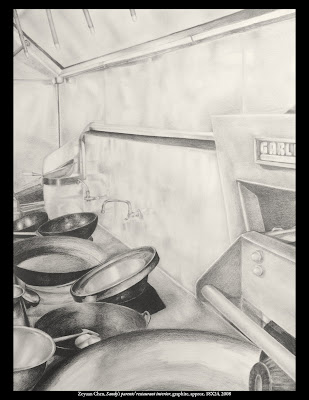

Self-portrait, graphite, approx. 18X24, 2007 Sandy’s parents’ restaurant interior, graphite, approx. 18X24, 2008

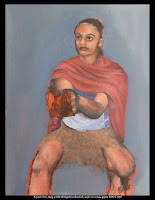

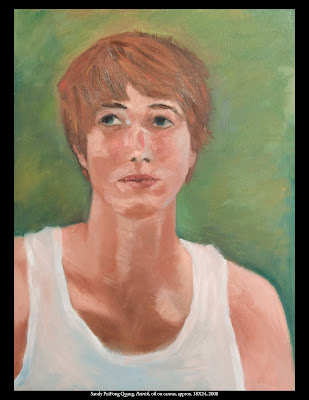

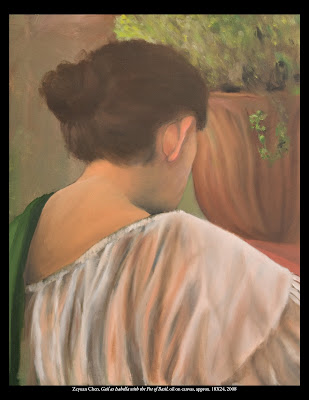

Sandy’s parents’ restaurant interior, graphite, approx. 18X24, 2008  Gail as Isabella with the pot of Basil, oil on canvas, approx. 18X24, 2008

Gail as Isabella with the pot of Basil, oil on canvas, approx. 18X24, 2008

Classroom window molding, graphite, approx. 18X24,

Classroom window molding, graphite, approx. 18X24,