|

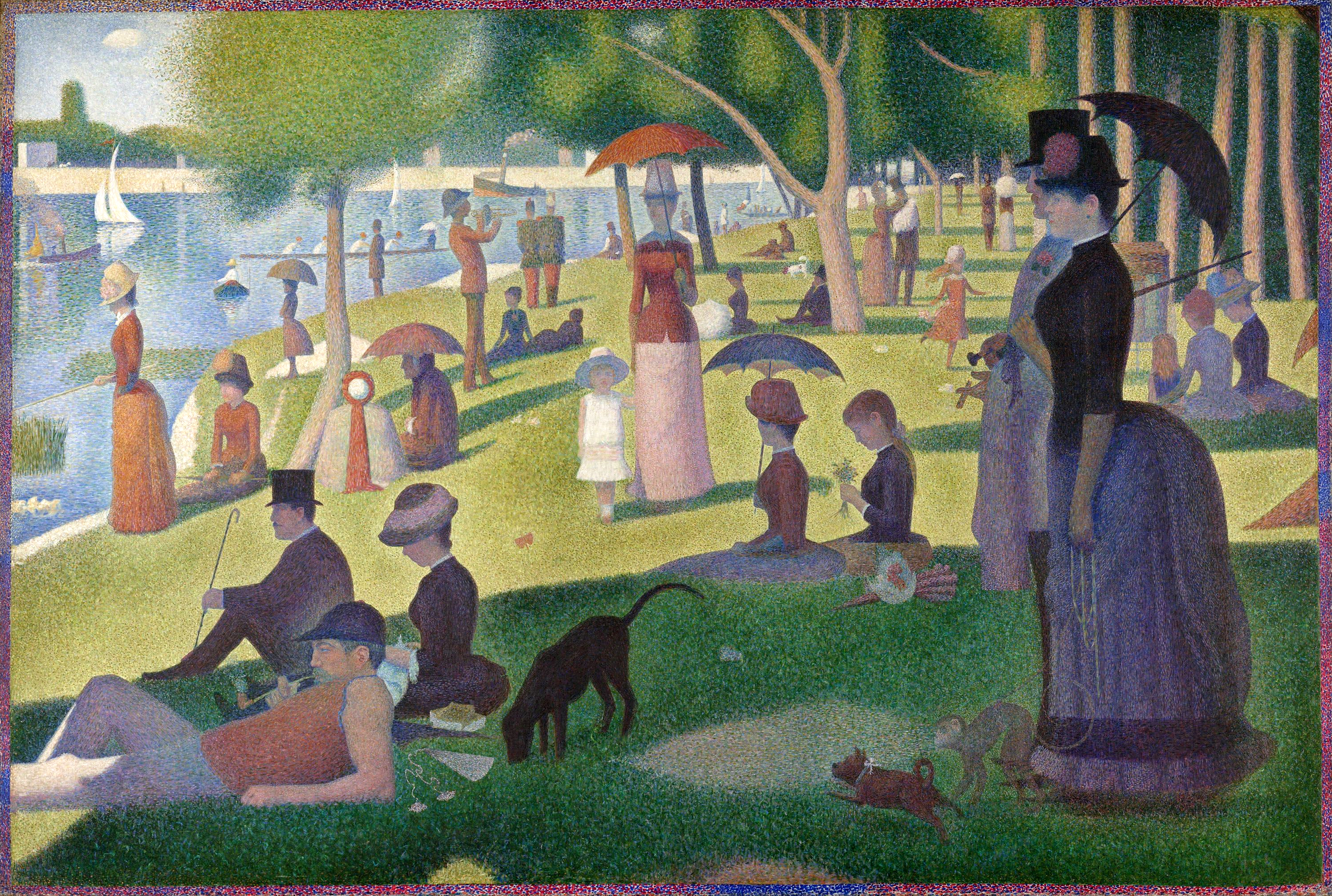

| Winston Churchill, The Goldfish Pond at Chartwell, 1932. I think any artist would be proud to have painted this. |

When we were painting in Camden at my first workshop last month, an elderly gentleman asked Sandy if he could take her photo with her painting. “After all,” he said, “you could be the next Winston Churchill.”

One presumes he meant Winslow Homer, but I suppose he could have meant Churchill. Churchill was a fine amateur painter.

|

| Winston Churchill, A View From Chartwell, 1938. Storm clouds may have been gathering over the Sudetenland, but Chartwell remained Churchill’s personal Garden of Eden. |

“Whether you feel that your soul is pleased by the conception of contemplation of harmonies, or that your mind is stimulated by the aspect of magnificent problems, or whether you are content to find fun in trying to observe and depict the jolly things you see, the vistas of possibility are limited only by the shortness of life. Every day you may make progress. Every step may be fruitful. Yet there will stretch out before you an ever-lengthening, ever-ascending, ever improving path. You know you will never get to the end of the journey. But this, so far from discouraging, only adds to the joy and glory of the climb,” wrote Churchill.

Of course, Churchill’s nemesis, Adolf Hitler, was also (famously) a painter. In Mein Kampf, he wrote about his rejection from the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Later, he tinted and sold postcards of scenes of Vienna, and haunted Munich artists’ cafes in the vain hope that other artists might help forward his career. He was alleged to have told British ambassador Nevile Henderson, “I am an artist and not a politician. Once the Polish question is settled, I want to end my life as an artist.”

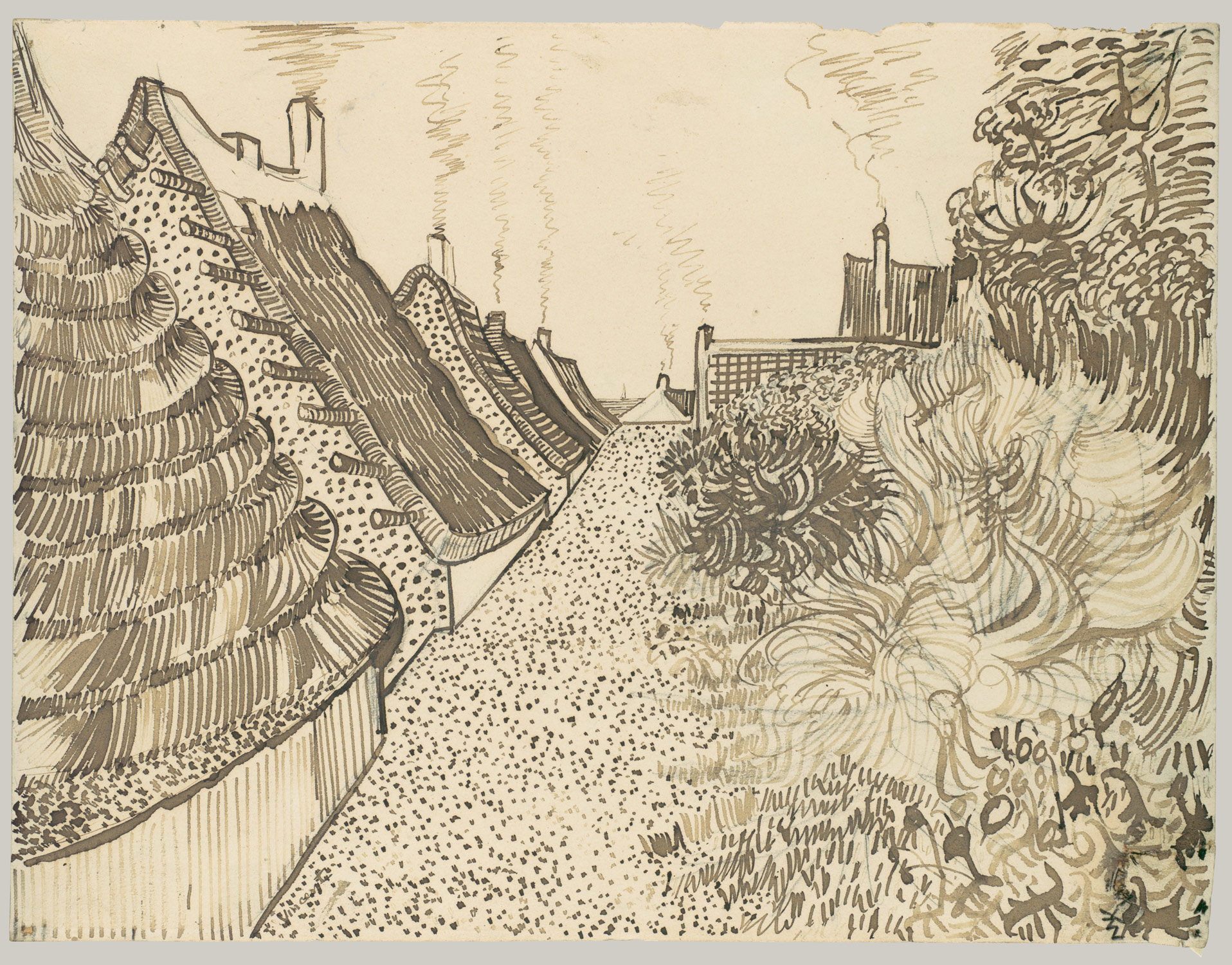

|

| Adolf Hitler, Perchtoldsdorg Castle and Church. |

Hitler had drafting ability and might have succeeded in his aspiration to become an architect, had he been able to muster up the academic credentials to get into school. But there is something excessively sentimental about his painting. Combined with the rigidity of his drawing, his work is, indeed, very off-putting—and I don’t say that just because he was one of history’s great mass murderers.

|

| Adolf Hitler, Alter Werderthor Wien |

A third titan of WWII also took up painting, albeit after his tenure as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. Seeing his friend Churchill at work may have influenced General Dwight D. Eisenhower to take up painting, or he may have been influenced by watching observing the artist Thomas E. Stephens paint Mamie’s portrait. Maybe he just had time on his hands after the war.

|

| President Eisenhower at his easel. |

Eisenhower wrote to Churchill in 1950: “I have a lot of fun since I took it up, in my somewhat miserable way, your hobby of painting. I have had no instruction, have no talent, and certainly have no justification for covering nice, white canvas with the kind of daubs that seem constantly to spring from my brushes. Nevertheless, I like it tremendously, and in fact, have produced two or three things that I like enough to keep.”

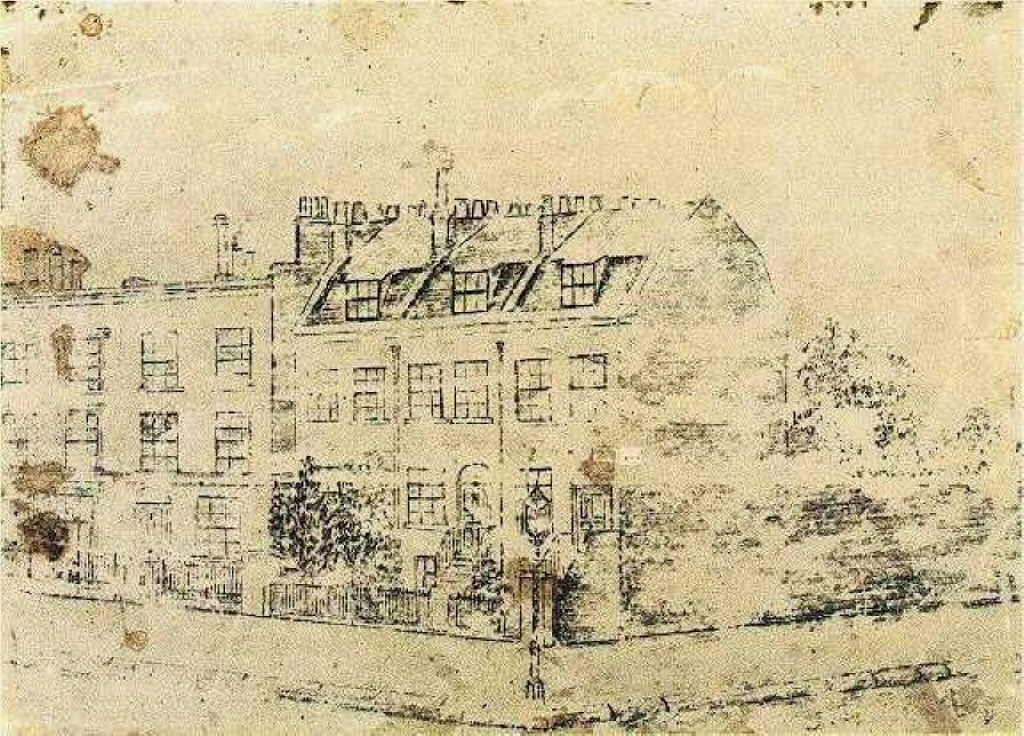

|

| Dwight D. Eisenhower, The Telegraph Cottage, 1949 |

Eisenhower’s self-assessment seems apt, but the question of talent is beside the point. Whatever the merits of their painting, Churchill, Hitler and Eisenhower are going to be remembered for their other achievements.

The painterly impulse isn’t completely unknown among modern politicians. A few months ago, a hacker revealed daubs by former president George W. Bush. (I wish he’d take one of my Maine workshops; he would really benefit from it.) But in a world where politicians seem more likely to go in for sexting and rent boys, painting seems like a quaint past-time.

Even though Rockland is just up Route 1 from Kennebunkport, I am kind of doubting George Bush will be in my class. But if you’re signed up for my July workshop in mid-coast Maine, you can find the supply lists here. There’s one more residential slot left; I’m dying to know who is going to fill it. August and September are sold out , but there are openings in October! Check here for more information.