|

| On the Delaware River, 1861-1863, George Inness |

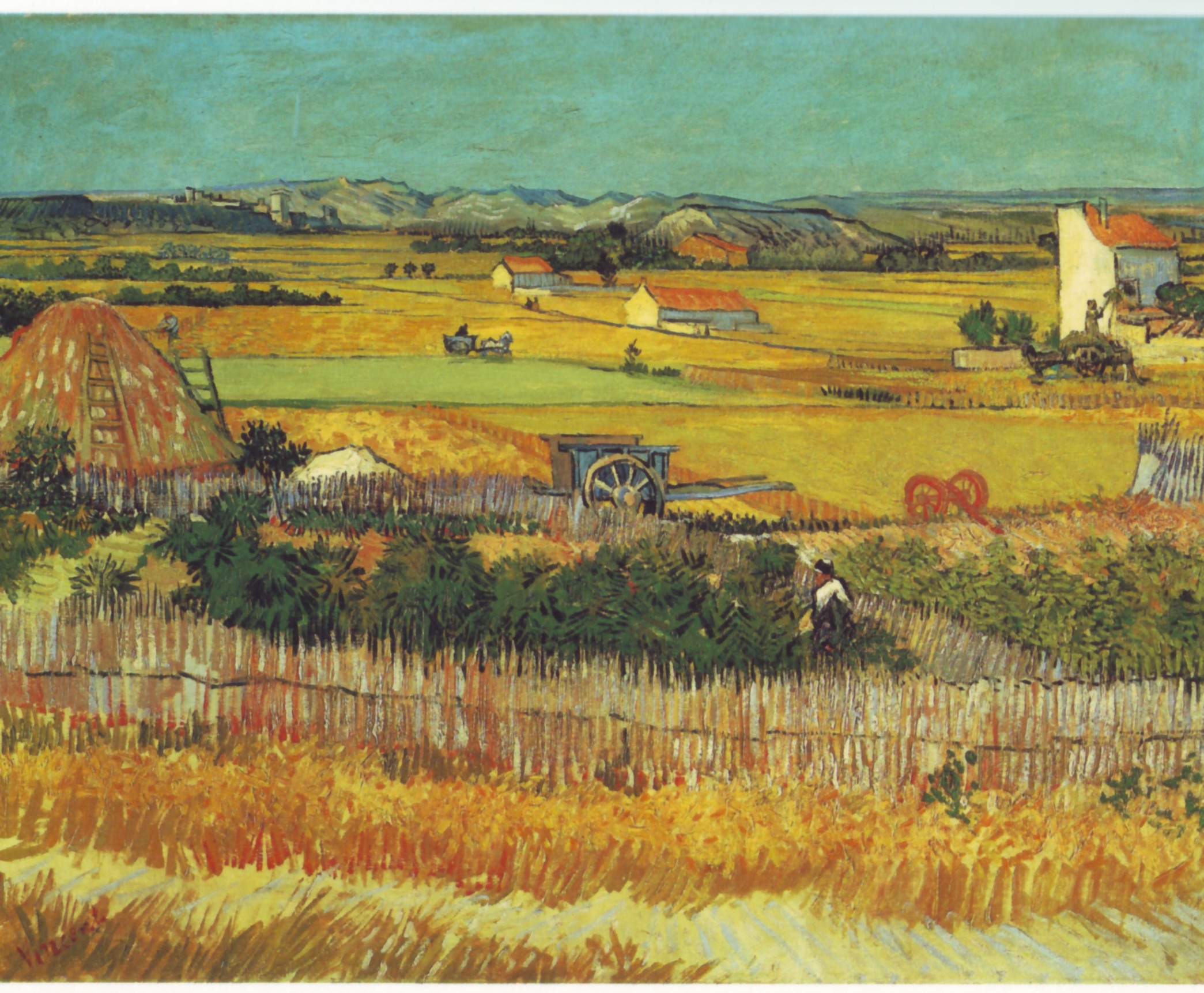

Harvest at La Crau with Montmajour in the Background, 1888

|

| Harvest at La Crau with Montmajour in the Background, Vincent Van Gogh, 1888 |

Le pont de Narni, 1826

|

|

Le pont de Narni, 1826, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, oil on paper, the Louvre.

|

Beamsville, 1919

|

| Beamsville, 1919, Frank Johnston |

A world without art is a world without common culture

Yesterday I railed about the educational establishment, which practices intellectual gavage on our children at the expense of creativity. Perhaps they should remember that all, or nearly all, of the unifying icons of the American experience were created by artists.

|

| Daniel Chester French’s colossal Lincoln in Washington’s Lincoln Memorial |

Maya Lin was a 21-year-old architecture student when her design was selected for the Vietnam Memorial in Washington. Her design submission was highly controversial, with great public outcry against its nihilism and austerity.

This is your world without art

|

| This is your world without art. |

Art is a luxury only if civilization is a luxury. We are fools to believe we humans don’t live primarily in the emotional and physical realms. (Maslow’s Heirarchy of Needs is a curiously intellectual way of expressing this truth.) Ignore the physical and emotional needs of children, and watch just how much they don’t learn.

We can’t afford art? The as-yet blank check for implementing Common Core standards is estimated at anywhere from $1 billion to $16 billion nationwide.

The one thing every plein air painter should know

| In its natural state, a plastic shopping bag is a pain. It bounces around, wraps itself around stuff, and generally takes up far more space than its real volume. |

| First, smooth the bag out so the corners are flat and the handles are straight. |

| Then fold the bag in half… |

| And half again. |

| From the bottom, start folding it in triangles… |

| ...until you reach the handle. |

| Almost there! |

| Fold the handle back toward the bag, also in triangles. |

| And stuff it in the gap. |

| Yeah, like this. |

| Voila! A perfectly neat bag to drop in your backpack. |

| And if you keep a stash of them, you might qualify as OCD Painter of the Year. |

| But THIS, my friends, is the sound of a new computer installing Adobe Creative Suite. Tomorrow I might actually start to make sense again! |

Sixteen scurvy navvies

|

| The Halve Maen passing Hudson Highlands, 40X30, oil on canvas (also available in Giclée print) |

I painted it to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage in the Halve Maen. He and a small crew of sixteen scurvy navvies sailed from Amsterdam to Newfoundland. From there they turned south, skimming along the Atlantic coast until they eventually made landfall at Cape Cod.

They then sailed to Chesapeake Bay, after which they worked their way north along the coast, poking into bays and inlets. Much of the Hudson River is a tidal estuary of brackish water, so Hudson and his crew must have been thrilled as they headed north, believing they had finally found the fabled Northwest Passage. They sailed up to modern-day Albany before realizing their mistake.

|

| The Last Voyage Of Henry Hudson, John Collier, 1881. I prefer to believe they made it to the south end of James Bay and walked back to habitable climes, stopping at a Tim Horton on the way. |

Hudson wasn’t the first European the natives had encountered; Albany had a French trading fort in 1540. Verrazzano had encountered the Lenape when he sailed in Hudson harbor in 1524. But these people were not the forerunners of colonists in the way Hudson was. The Dutch, English and Iroquois inexorably displaced the Lenape and Mohicans in the Hudson Valley. Where they failed, smallpox succeeded.

I turned the natives’ faces from the viewer because I don’t want to presume their reaction—probably because I have no idea what my own reaction would be. In making the boat so tiny, I was taking a page from Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who frequently put the significant action of his paintings in a corner of an otherwise panoramic canvas.

|

| Headwaters of the Hudson (Lake Tear of the Clouds), 40X30, Oil on Canvas (Private Collection) |

I also painted Lake Tear of the Clouds (which is the headwater of the Hudson) for the same show. Although I used a misty Adirondacks highland setting for it, it is not in fact a pool in which a canoe would likely be abandoned. The canoe in the painting was inspired by one I saw in a tidal pool at the Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation near Eastport, Me. The connection between the Adirondacks and Maine is deep and not easily fathomed.

Join us in October, 2013 at Lakewatch Manor—which is selling out fast—or let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in 2014. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

Oh, the places we’ve been!

If the puff of blue smoke and whiff of brimstone hadn’t convinced me, the Last Rites performed by the IT department proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that my laptop had suddenly morphed into a doorstop.

It’s possible that my computer expired rather than look at any more dresses on the Internet. However, I recently received a chunk of change in exchange for a painting. My dear Prius is eight years old and has been gunning for a spa day. It’s a very smart car, so I knew enough to walk to the bank to deposit the check. But it never dawned on me that my laptop might actually pay attention to what I enter into its spreadsheets.*

It is now time for that most painful of tasks: comparison shopping. There are a million ways to make a wrong choice in today’s marketplace. (Some people enjoy shopping. Imagine that.)

Should I get a tablet? I travel a lot; my luggage is always too big. My IT department immediately vetoed that. I can hardly argue since he programs on both platforms. “A tablet will never give you the power you need and the apps are still primitive in comparison,” he said.

| Former laptop, now doorstop or paperweight. Goodbye, Old Paint. |

I purchased this laptop before the Great Crash of 2008. That’s a good long life for a laptop, but my kids have had the same brand and their laptops both had catastrophic fails. So brand loyalty alone is no guide.

At this point, someone always suggests that I buy a Mac. Been there, done that. I don’t want to pay the premium for the hardware or buy new software. PC architecture allows my IT department to upgrade hardware every time I start whining. (He has to; he’s married to me.)

We keep a spare laptop for emergencies. I can type on an old version of Word but there’s no card reader and no way to access any of the 15,000 or so photos on my hard drive. “This is why I tell you to store your photos on the server,” grumbled the IT department. Then he fished around and found me an old external card reader.

I always look for the silver lining. Perhaps my new computer will allow me to comment on my own blog, I mused. And I was chuffed to realize that my go-to guys for computer advice—besides the afore-mentioned IT department, of course—are my three daughters.

*I know inanimate objects watch carefully to see if you recently got paid, but how does my dentist know when I’ve suddenly come across a little gelt? He just told me I need a new crown.

Join me in October, 2013 at Lakewatch Manor—which is selling out fast—or let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in 2014. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops! If you want to study in Rochester, drop me a line here.