|

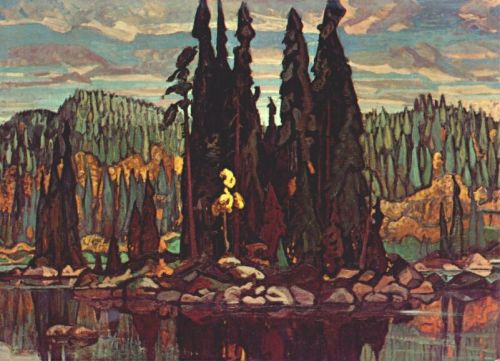

| If one can make a pretty photo out of squirrel ectoplasm, one can make anything beautiful! |

By the time I’m done doing my five miles and my exercises, I’m usually ready to go back to bed.

Yesterday, I did exactly that. I’m worn out.

In May, a large stack of empty frames clattered to the floor from an overhead shelf. As they fell straight down into an out-of-the-way corner and I was in my usual dither, I ignored them.

It’s been a pretty crazy summer, but I have an even crazier autumn ahead: two trips to Maine, a trip to Rye, and a daughter’s wedding, all happening in the next six weeks. And I have to get my winter supply of canvases in before the snow flies.

To that end, I decided I should use this glorious fall day to straighten my workshop. I picked up the pile of frames only to learn that they had crushed a squirrel to death. Months ago.

I confess: I’m a screamer. After Sandy Quang poked the remains with a stick, she was a screamer too. The IT department is at his day job. His sole contribution was a text that read, “So, meat’s back on the menu!” It was left to poor Charles Wang to dispose of what was left of the corpse. He was remarkably calm about it, considering that both Sandy and I were pretty well off our respective nuts.

“What are we going to do about this mess on the floor,” I asked Sandy.

“Take a picture,” she responded (like the true artist she is). So I did.

I decided that spraying bleach everywhere would probably work about as well as burning my garage down. By the time I was done explaining to our mailman what the ruckus was about and running to the store for bleach, my energies were quite restored. As soon as that bleach has burned its way through my floor, I’m ready to make a thousand canvases!

Join me in October, 2013 at Lakewatch Manor—which is selling out fast—or let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in 2014. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!