|

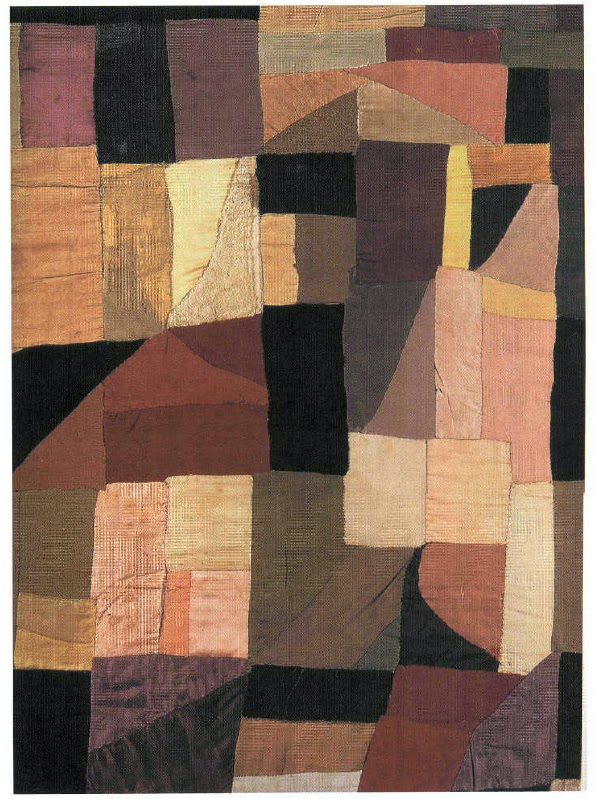

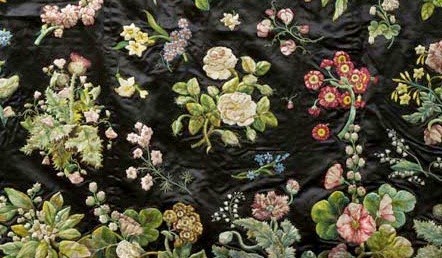

| Doodled illumination, by Gail Kellogg Hope |

My pal Gail Kellogg Hope is home chasing a toddler around. Gail’s a trained artist, with an MA in art education from RIT. Occasionally she gets bored and does something ‘arty’ although she doesn’t have the mental space or energy to paint seriously right now.

This is why she ended up making the illuminated borders here. They’re pen-and-wash doodles, and she thought she’d make a set of them as cards as a gift for someone. I thought they were sweet and told her so. Then she showed them to a group on Facebook, where she received a scathing rip by a fellow artist about her lack of detail.

|

| Doodled illumination, by Gail Kellogg Hope |

There is a place for constructive criticism, and Facebook—in general—isn’t it. This is not to say that I never critique work on Facebook, since I have hundreds of artist friends and we’re always bouncing images back and forth. But critique is best done one-on-one and among people you trust.

|

| Doodled illumination, by Gail Kellogg Hope |

The artist has just presented you with the best work he is capable of at this time. He is profoundly attached to it. Like a parent, he is blind to its weaknesses. Yes, you can gently point out ways to make the work stronger—and that is, after all, the primary job of a teacher—but you had better start from the position that the work is fundamentally good.

This is why nice people sandwich the negative between two positives: “I love your use of color/the horizon is crooked/your composition is strong.” Practice that technique. It will come in handy all through life, not just in art.

|

| Doodled illumination, by Gail Kellogg Hope |

I have a painting in my studio that I wrecked after a bad critique session. Fifteen years later, I know that the comment that crushed me—“It’s like a bad Chagall”—was neither true nor helpful. I would hate to think I ever did that to another student.

Be honest, but if you don’t have anything good to say, then you probably shouldn’t be critiquing work at all.

|

| Doodled illumination, by Gail Kellogg Hope |

I will be teaching in Acadia National Park next August. Message me if you want information about the coming year’s classes or this workshop.