Two artists whose paintings in adversity remind us that we don’t always have to paint from our happy place.

|

| Forgotten Man, 1944, Maynard Dixon, courtesy Wikiart |

Maynard Dixon

Maynard Dixon is less remembered than his second wife, photojournalist Dorothea Lange, but they shared the same social justice concerns. Dixon had just finished a mural for the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix and was scheduled to start its mate when the stock market crashed in October of 1929. The Great Depression defined life in the 1930s, for artists as much as anyone.

Dixon finished 282 pieces from 1930 to 1935. He sold just five. That wouldn’t have even covered the cost of the paint.

Dixon, Lange, and their children lived from 1929 to 1931 in a borrowed adobe building in Taos. “Well, if we can drag it out here until Christmas I may show something myself—though it will be hell trying to out it. Other than financially we are going fine and wish you the same,” he wrote a friend in 1931.

|

|

Abandoned Ranch, Maynard Dixon, 1935, courtesy Wikiart |

Today we remember Lange as the voice of the downtrodden, but Dixon was equally passionate about their plight. Although he was a well-known painter of the southwest, he began to paint his fellow sufferers, particularly those encamped near his California studio.

“The most interesting thing in this country for me is a sense of dark tragedy, imminent, and just beneath the light surface: the unchangeable Indians, always facing toward death, the starving Mexicans, already half dead, and the garrulous gringos oppressed by a vague feeling of impending doom,” he wrote.

During the summer of 1933 Dixon and his family camped through southern Utah. They stopped at Boulder Dam to observe its construction. Six months later, Dixon returned with a Public Works of Art project grant to document the project. This combined Utah work was exhibited in San Francisco the following year. Not one of the forty paintings sold.

Algernon Newton

|

| The Surrey Canal, Camberwell, 1935, Algernon Newman, courtesy of the Tate |

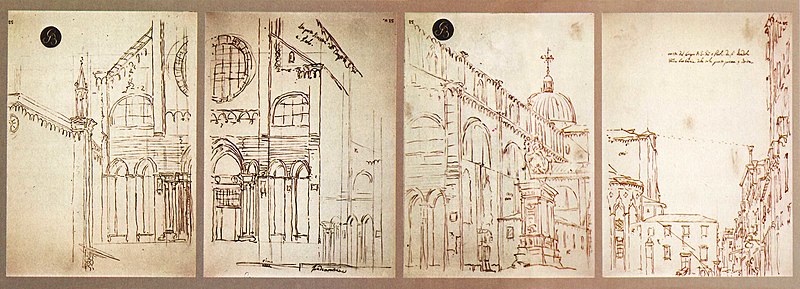

Algernon Newton had a wonderful pedigree as a painter; he was the grandson of one of the founders of Winsor & Newton. However, he learned to paint in an atypical way, avoiding the straight route through the Academy. That allowed his own interests to blossom. While his peers were immersed in abstract-expressionism, he was studying Canaletto.

Invalided out of service at the end of the Great War, he was reduced to selling pictures on the street. It was a horrible time, when his fellow veterans were begging. And then there was a new, unseen enemy, the Spanish flu.

|

|

The Regent’s Canal, Twilight, 1925, Algernon Newton |

Newton’s sympathies were very much with the common man and his environment. “There is beauty to be found in everything, you only have to search for it; a gasometer can make as beautiful a picture as a palace on the Grand Canal, Venice. It simply depends on the artist’s vision,” he wrote.

In America, he would have been following in the footsteps of the Ashcan School. In London, he chose a middle way, creating empty, eerie portraits of somewhat-dilapidated Regency and Victorian terraces, preferably fronting bodies of water. Unlike Canaletto’s compositions, his are curiously uninhabited, which gives them a strange modernity. As Martin Gayford wrotethis week, “Especially now, in this odd era of daily walks in semi-deserted towns, he often comes to mind.”