As our tow truck brought us back into Brandon, an enormous fireball erupted to our right. “Oh, that’s just the airport,” the driver, Gerald Dedieu, said. It turns out that they do firefighting practice there in the off hours.

It was clear that we were going to kill some time in Brandon, so Gerald suggested we head down to his hometown of Souris in our loaner car. Souris has a creek, a suspension bridge, and a pretty setting, he promised us.

“Downtown,” by Carol L. Douglas

The suspension bridge is Canada’s answer to the Jubilee Memorial Watering Trough. Every town apparently has one, Souris included. Instead of painting that, or Souris’ peacocks, I decided to paint a block of their downtown.

There is some debate about where the geographical center of America falls. It’s either in Rugby, ND, or just east of Winnipeg, MB. It hardly matters. Either way, virtually everyone on our continent is a southerner. Furthermore, most have not ventured north of the true Mason-Dixon Line, which is the 49th Parallel.

Minnesota owns a wee bit of land north of the 49th Parallel, due to a surveying error. The Northwest Angle, as it’s called, is cut off from the United States byLake of the Woods. To get there from the US, you need a boat, an ice bridge, or a passport, because the only roads come in from Manitoba. It’s got a population of 152 people and a land mass of about 600 square miles, of which 80% is water. This being a strictly Canadian visit, we did not detour there.

We did, however, visit West Hawk Lake. This is Manitoba’s deepest lake, at 115 meters. It was formed by a giant meteor, and its size is impressive.

West Hawk Lake is on Historic Route 1, so we ventured up that road looking for a glimpse of history. Alas, it was apparently recently bombed, so broken was the asphalt. We turned back.

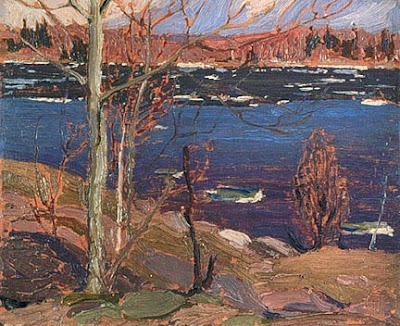

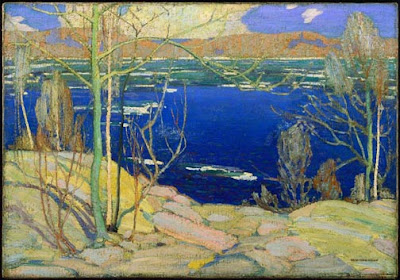

I set up to paint Lake of the Woods from the Discovery Center at Kenora. It was a great bonus, in my opinion, to have genuine running water and a soda machine at my disposal. Alas, there was a wedding being held there later in the day, so I was shooed along. I relocated a mile or so to the north.

I’ve switched mediums to Galkyd Light, since it’s all I could buy in Calgary. I’m having a hard time adjusting to it. It feels soupy. This is showing up particularly in my mark-making and in water reflections. I was struggling so much trying to find a workable scheme for the water at Lake of the Woods that I forgot to paint in the remainder of the sky.

Western Ontario looks a lot like the Maine woods: granite and spruces and Jack Pines, and a whole lot of water. I was shocked, therefore, on arriving at Thunder Bay. Growing up listening to Canadian radio, I had always pictured it as a romantic place far west on the Great Lakes. Its waterfront is actually a lot like South Buffalo, which is where my people come from. The same neat workingman’s cottages march down to the same vast grain elevators.

The difference is that Thunder Bay’s grain elevators are still working. That’s because freighters take on grain here, rather than offload it. Today that grain goes right out the St. Lawrence into the world. Buffalo—the world’s first cross-docking station—is unnecessary.

I expected that one Great Lake shore was pretty much the same as another, but I was wrong. Here, red granite tops rough hills that drop to the lakeshore. This exposed granite is part of the vast Canadian Shield that forms the bedrock core of our continent.

As we drove east along the lakeshore, dusk dropped like rose-colored silk. A bear cub gamboled along the shoulder of the road. We were back in moose country. It was time to stop for the night.