It wasn’t Santa Claus but it was magic nevertheless.

|

| Santa toy, oil on archival canvasboard, $435 in a narrow silver frame, available this month through Camden Public Library. |

We were raised without Santa Claus, my parents believing that it was bad to lie to children. Furthermore, my mother was inept at gift-buying. It was the Swinging Sixties, and my friends were getting Barbies, slot cars and record players. We got winter gloves, long underwear, clothes and socks.

I don’t remember feeling particularly deprived about it. We were rich in playthings. We had dirt bikes, dogs, horses, chickens, cows, and a sailboat. Mom was just whimsy-impaired. There were never Barbies or Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots when we were little.

|

| Christmas Presents, sold this month through Camden Public Library. |

We were not churchgoers, so nothing set Christmas morning apart. We would open our gifts, have breakfast, and then do as we always did on weekends and holidays—go outside and scare up some fun.

Christmas Eve was the holiday that mattered. Our grandmother’s home in South Buffalo was an hour’s drive in perfect weather. The weather in Buffalo in December is often horrible. Blizzards blow in across Lake Erie in the so-called ‘lake effect’ storms of early winter. Yet we never missed a year, even when it meant inching along the Thruway in white-out conditions.

There was always a battle for a window seat, because there was no car radio or light to read by. Instead, there was frost on the windows, in which one could draw pictures, and a kaleidoscope of winter scenes.

|

| Christmas Eve, oil on archival canvasboard, $435 in a narrow silver frame, available this month through Camden Public Library. |

It’s said that my Aunt Mary once laid my infant cousin Liz down in the huge pile of coats on my grandmother’s bed and forgot her. I can no longer remember if that is true or not.

What I remember most was the noise. The tables were set down the center of my grandmother’s apartment, and we were seated in descending order of age. There was no segregation of kids from adults. My grandmother was an immigrant and a young widow. She was the head of her clan, with six kids and 25 grandkids. In a sense, we were her life’s work, and she liked seeing us all together.

There was no dishwasher, of course. After dinner, aunts and cousins retreated to the kitchen to clean up, and my grandmother’s standards were exacting. That might gall today, but we didn’t mind. I got to know my cousins standing in Grandma’s kitchen drying plates.

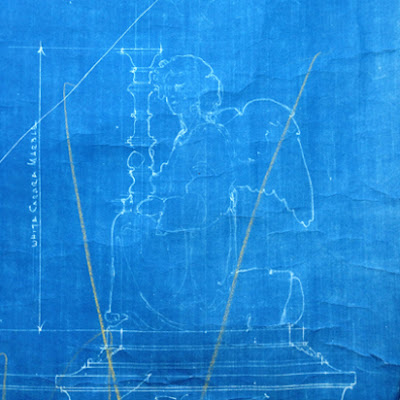

|

| Christmas Angel, courtesy private collector. |

If it was not storming, my parents might be persuaded to go to Midnight Mass at my grandmother’s parish church. The hush, the candles, and the strange beauty of Catholic liturgy were all alien and yet so familiar. I’d been watching it from outside for my whole short life.

And then, the long drive home through the snow. Dozing, perhaps, but never really sleeping, the squeak of tires in snow, windshield wipers flapping. Dark roads and sometimes moonlight. It wasn’t Santa Claus but it was magic nevertheless.

My sister Ann died, and then my brother John, and then my cousin Frankie. My dad pretty much fell apart after that. Grandma got too old to make the white pasta and baccalà, so the aunts took over with sheet pans of lasagna. The Christmas feast wandered, irresolute, from house to house until it finally died.

But Christmas Eve remains one of my favorite days of the year. We’ll fry fish tonight, and video-chat with our kids and grandkids, and then wait with the rest of the world, in a silent hush of anticipation. Tonight, we celebrate the Incarnation, when God sent his only son to deliver us from our own stupidity. Of all the gifts I’ve ever received, that understanding is undoubtably the greatest.