I wanna go north, east, south, west

Every which way, as long as I’m movin’…

Every which way, as long as I’m movin’…

My method of packing is to start with the important stuff, like vacuuming the floor joists in the basement. That’s excitement speaking. Like Ruth Brown, I’m happy as long as I’m moving. I’ve been home in Maine since February, when I went to Pecos, NM to paint with Jane Chapin. For my mid-Atlantic friends, the plein airseason has already started in earnest, whereas we in the north are just starting to believe the snow is finally behind us.

My current adventure started with a deceptively-simple question. Could I do a portrait “in the manner of Francis Cadell?” That the inquirer differentiated between “style” and “manner” meant that he wasn’t asking me for an imitation Cadell painting. I wouldn’t know how to do that.

|

|

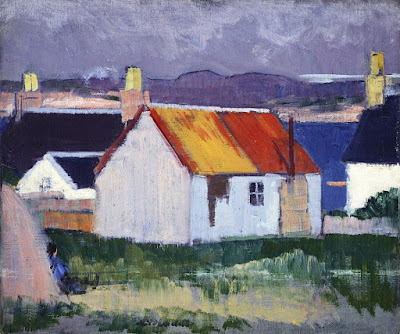

Iona Croft, 1920, by Francis Cadell, courtesy National Galleries of Scotland

|

“In the manner of” has a specific meaning in art history, which is that it was done by a follower of a particular artist, but after the artist’s death.

Style, on the other hand, is the mark-making, composition, color palette and other visible attributes (or method of working) that give the appearance of the finished work. Style ties a painting to other works by the same artist, or to a specific period, genre or movement. It’s the art historian’s principle tool in classifying artwork. I can never be a Scottish colourist, any more than I can be a Canadian Group of Sevenpainter. Each of us is tied too closely to our own time and place in history, and imitating the Dead Masters is a sure path to mediocrity. But we can think seriously about the values those painters brought to their work.

Cadell had a palpable affection for his subjects: human, still life or landscape. Even so, people and objects were always somewhat subservient to their settings, which were frequently the Georgian rooms he occupied in Ainslie Place in Edinburgh’s New Town. Ironically, I’ll be painting just down the street, in a similar Georgian townhouse.

|

| Full stop, by Carol L. Douglas. Well, we both like purple. |

Cadell chose beauty over stylishness. The difference is depth and staying power. It takes some scratching to get down to fundamental truth. It’s easier to go for pretty scenes, cheap symbols or trendy commentary. But those things are only transient.

My old friend and model Michele Long used to say that figure painting was a collaboration between the artist and the model. I think that was a profound insight, but I’d add a third player: the audience, present and future. Art is primarily communication, and that requires that the subject, artist and audience all bring something to the engagement.

| Michelle reading, by Carol L. Douglas |

People sometimes ask me if there are paintings I would never sell. There’s one: my grandson Jake as an infant. (It was the last time he was ever still.) Once I’ve laid down my brushes, I don’t think of a painting as mine any longer. From that, it’s easy for me to realize that it was never really mine in the first place.

Thus, it isn’t about me, my skills, my whims, or my inadequacies, but about the subject and the viewer. That takes a lot of the ego out of the process, and makes me able to relax and enjoy painting.