|

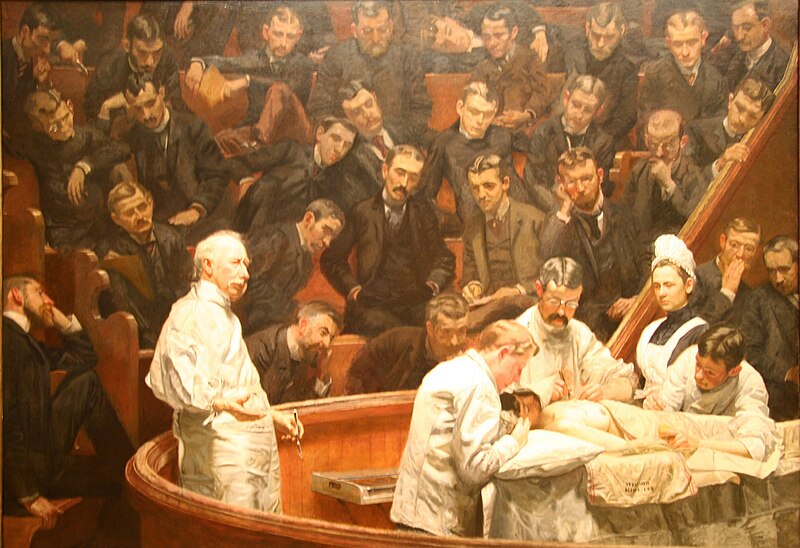

| A possible Matisse among the paintings exhibited at a press conference in Munich (from AFP/Getty Images via the Telegraph website). |

As the entire world knows by now, a cache of 1400 Nazi-looted artworks was found in 2012 in the apartment of an elderly man in Munich.

The pensioner first came under the suspicion of customs officials on 22nd September 2010 when he was seen traveling to from Munich to Zurich and back, with large amounts of cash, in a single day.

When they conducted further inquiries they discovered that he barely existed on official records: he paid no tax, held no social security records, and had never worked.

They then searched his flat and found the piles of paintings hidden behind cans of food in a squalid apartment. (The Telegraph)

|

| Another painting displayed at the press conference (from AFP/Getty Images via the Telegraph website). |

Cornelius Gurlitt apparently also owns a derelict house in an affluent suburb of Salzburg, Austria:

The gate to the back garden yawns open and a large crack in the backward-facing outer wall has been boarded up from the inside. Only this and some rusty latticed iron bars on the windows stand to deter intruders. (The Telegraph)

Leave aside the questions of how Gurlitt’s father acquired the work, what the Nazis really thought of so-called ‘degenerate art’, and why German authorities haven’t publicly identified the work so it could be repatriated to its former owners.

Ask instead what drove this man to hoard a billion dollars of stolen art while living in a hovel. These paintings—intended to bring joy and life—instead brought imprisonment and isolation. To me, that sounds like a spiritual problem.

“Artists tend to produce art as a vain bulwark against time, a gamble on posterity; and for many of the artists whom Hitler loathed, art was an explicit attempt to prevent him from getting the last word,” wrote Michael Kimmelman in the New York Times.

This may or may not be true, and it’s worth asking why we produce art. (Myself, I don’t know.) But it’s also worth asking why clients collect art, and what that means when the acquisitional urge is perverted. Obviously Gurlitt’s soul was somehow twisted by being the recipient of these paintings, but how, exactly, did that happen?

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)