|

| Saying Grace by Norman Rockwell, 1951 |

A Norman Rockwell painting sold at auction at Sotheby’s in Manhattan yesterday for $46 million. This was twice its pre-sale estimate of $15-20 million and a record for a Rockwell painting.

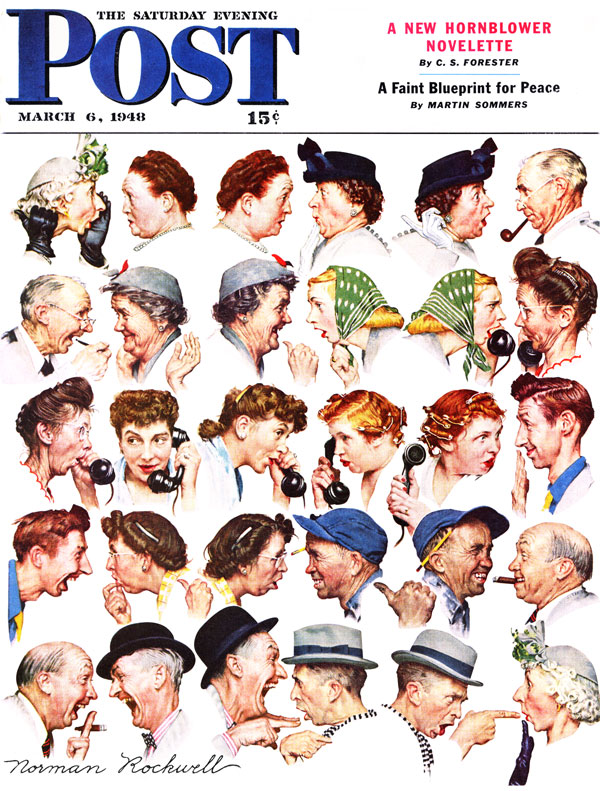

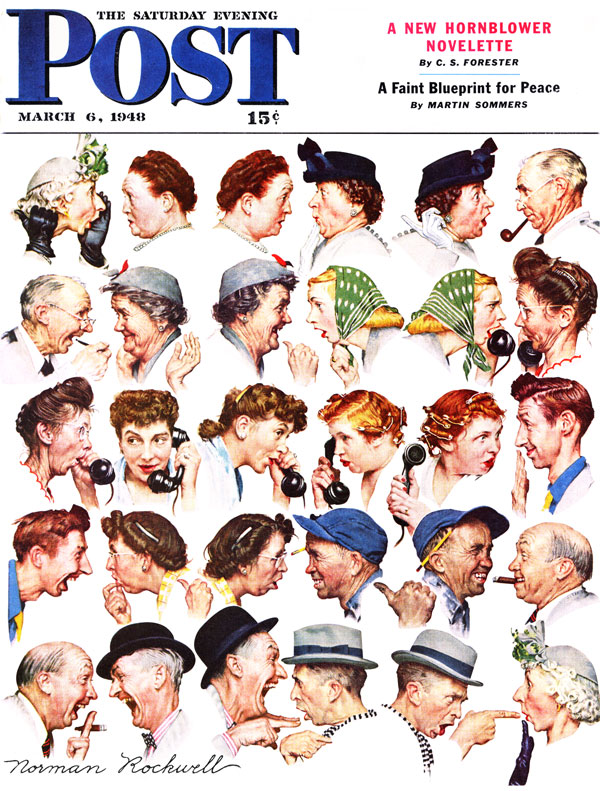

The painting, “Saying Grace”, was one of seven Rockwells in the auction. Two other Rockwell Saturday Evening Post covers, “The Gossips” and “Walking to Church,” sold for just under $8.5 million and a little over $3.2 million respectively.

These three paintings were formerly on long-term loan to the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. They were sold by descendants of Kenneth J. Stuart, the Evening Post art editor who worked with Rockwell for nearly 20 years. All three had been given to Stuart by Rockwell.*

|

| Walking to Church by Norman Rockwell, 1952. You can buy a signed print of this for approximately what Rockwell was paid for painting it, or you could have gotten the original yesterday for about a thousand times his fee (not adjusted for inflation). |

Rockwell was paid $3500 for “Saying Grace” in 1951. That translates to roughly $32,000 in today’s dollars. This would be tremendous money for any illustrator today, and shows how highly illustration was valued in mid-century America. However, even adjusted for inflation the sellers got around 1500 times the price Rockwell received for actually painting the thing.

Sadly, if you’re doing your job right as an artist, this is how it goes. This might seem counterintuitive when considering such a popular artist as Rockwell. But even during the Golden Age of Illustration, few people considered illustrators to be fine artists. It’s taken time and distance for us to see Rockwell, Howard Pyle, or N.C. Wyeth as the great artists they were. But consider John James Audubon, William Blake, or Albrecht Durer. Their work, too, has become more rarified by time, but they were also, fundamentally, illustrators.

|

| The Gossips by Norman Rockwell, 1948 |

At any rate, the few hundreds or thousands you get for your work today will, if all goes as planned, translate into a fortune in some future swank showroom in, say, Abu Dhabi or Macau.

*Having done my share of illustration, this seems like a squishy provenance to me. It’s just as likely that the work got shoved behind a cabinet and forgotten, and Stuart had the good sense to take it home rather than let it be thrown away.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

.jpg/409px-Piss_Christ_by_Serrano_Andres_(1987).jpg)

.jpg)