It’s the season when we’re trapped at parties by slightly squiffy people pontificating about art. Here’s a handy glossary of terms to help you hold your own.

|

|

The Waterseller of Seville, 1618, was Diego Velázquez’s masterpiece, meaning the painting that gave him the rights and privileges of a master under the guild system. It established him in the canon of western art. Courtesy the Uffizi Gallery.

|

Bravura means a spirited, florid passage of music requiring great skill from the performer. The word came to English in the eighteenth century from the spirited, florid Italians. There’s a sense of dash and brilliance in there, too. Today, we talk about the performer as much as the piece.

How to use this in a sentence: “After years of using a roller, I was inspired by his bravura brushwork.”

Canon originally meant a rule or decree of the Church, the books of the Bible that were accepted as legitimate, and the list of proven saints.

From this, canon came to mean the masters, masterworks, rules, and principles in any field of study, including art. Canonized artworks are the ones we venerate like saints, but canon also includes the people who made them and the theories that drove them.

How to use this in a sentence: “But of course, darling, the canon is absolutely dripping with Dead White Males.”

|

|

The Scream, 1893, Edvard Munch, courtesy of the National Gallery of Norway

|

Expressionism was all the rage in the first half of the twentieth century, when there really was something to scream about. It is subjective, distorting reality for emotional effect.

How to use this in a sentence: “Expressionism was a reaction to the bleak outlook of the time. For some reason I always think of it at these openings.”

Figurative doesn’t mean artwork with human figures in it. It just means the painting includes something you can actually recognize. This isn’t limited to realism, since there are plenty of people drawing recognizable things out of their own heads.

How to use this in a sentence: “My move to figurative painting was a purely mercenary decision.”

|

|

Untitled, c. 1943-44, screen print, Jackson Pollack. His work is all gesture. Courtesy MoMA

|

Gestural artwork includes dynamic, sweeping marks. It’s informal, spontaneous, and abandoned. In the twentieth century, it meant Action Painting. This was a branch of Abstract-Expressionism centered on the subconscious and the act of creation itself.

How to use this in a sentence: “I wish he’d kept his gestural work on the canvas. This stuff will never come out.”

Masterpiece originally meant the piece that a journeyman submitted to his guild to become a master of his craft. Today there’s no guild system, and the word is now invested with all kinds of fawning and awe. It really needs to be cut down to size.

How to use this in a sentence: Look suitably stunned and exclaim, “A masterpiece!” Repeat indefinitely.

Modeling is the rendering that defines the volume of the subject. Modeling takes a back seat to brushwork in much modern painting, but it was a prized skill before the Impressionists.

How to use this in a sentence: “The tender, delicate modeling focuses our attention on the truck bumper.”

A Motif is a theme or image in a painting or icon. It is often repeated, but may stand alone. It’s identifiable and has meaning within the piece. It comes from the Latin motivus, which means “moving, impelling.” That tells us a lot about the role of motifs in painting.

How to use this in a sentence: “That motif makes him look like a third-rate Chagall.”

|

|

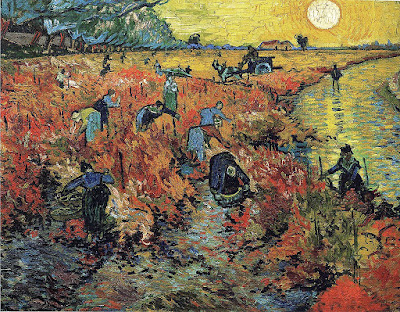

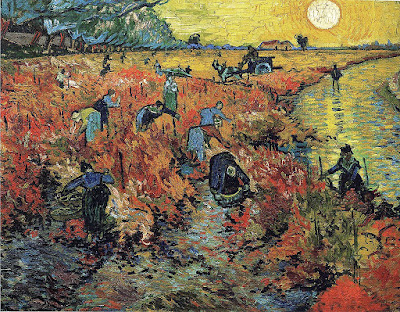

The Red Vineyard, 1888, Vincent Van Gogh, epitomizes painterliness. Courtesy Pushkin Museum.

|

Painterly: This means a surface where the brushstrokes aren’t hidden and blended. It’s less-controlled, unpolished, and fiery. Since it’s all the rage in actual painting, surprise people and apply it to another medium.

How to use this in a sentence: “He’s the most painterly of bartenders, with his playful focus and texture.”

Participatory:That’s interactive art where you, the viewer, get suckered into playing. In the worst examples, the artist will expound on your sensory experiences and responses in a most embarrassing way.

How to use this in a sentence: “No way.”

Perspective: This is the drawing system where an artist tricks you, the viewer, into seeing a scene or object receding in space. It can take the form of graphical perspective, where things get smaller as they go back, or atmospheric perspective, where the light and clarity change over distance. It’s still in use today, at least by people who can draw.

How to use this in a sentence: “His experiments with perspective are always a bit wonky.”

Virtuoso: Since the eighteenth century, this has meant a person with great skill, a master of his art form. The real question is how virtuosityderived from the same root word as virtuousdid.

How to use this in a sentence: “She’s a virtuoso with her brush cleaner.”