Four women and a set of jumper cables. Friends helping friends.

|

|

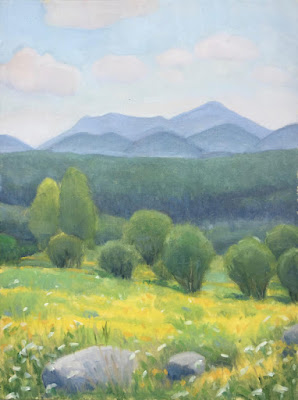

Approaching the bridge, 12X16, Carol L. Douglas (unfinished, because I have to knock down the gold in them there trees)

|

At Parrsboro in June, I met my friend Crista Pisano on the beach. She was tired, in a strange environment, and having a frankly bad day. “I got nothin’,” she lamented to me. It happens to everyone, and all you can do is commiserate. (She went on to do great work, by the way. That feeling is usually fleeting.)

That shouldn’t have happened to me here in Saranac Lake. I’d had a good night’s sleep. I know this area well. And yet I wrong-footed everything yesterday. I drove fruitlessly up and down the highway east of Lake Placid, feeling as if someone had moved everything I loved.

The essence of the Adirondacks is:

- Water

- Mountain

- Atmospherics

- Boulders

- Spruces and pines

- Man’s footprint

My goal this week is to pile as many of them as possible into a single painting, but it certainly didn’t start off well.

I finally settled on a view from

Adirondack LojRoad. The parking lot is a great jump-off point if you want to pack up Mount Marcy, but I’d need a mule for all my gear.

I painted looking down at a small bridge that crosses a tributary of the Ausable River. It was lovely but I was twitchy. Crista Pisano stopped by and I showed her the abandoned diagonal in my value sketch. “Put it back in,” she suggested, very reasonably. She pottered off to paint Avalanche Pass and I headed back to town for the Artist Reception at the

Hotel Saranac. It’s quietly swank after its recent renovation.

Detouring through Lake Placid, I realized I couldn’t find any of my lovely painting spots because I was on the wrong road. The west branch of the Ausable River is lovely in its own way, but it never hits the high notes of the main stream.

|

| I wasn’t willing to guess which one was hot. |

I was chatting with old friends over prosecco and hors d’oeuvres when Crista called. “My battery’s dead,” she said. My Prius couldn’t jump a kid’s electric ride, so

Chrissy Pahucki, her daughter Samantha and I headed out on a rescue mission. Chrissy’s nifty hybrid Highlander has all kinds of on-board displays, including a tire-pressure gauge, which told us that tire number two—whichever that was—was getting very low.

Still, first things first. Crista was in the dark in bear country without prosecco.

I know how to attach jumper cables, but was surprised to learn that Samantha, age 17, did as well. “My dad showed me,” she said. That’s a world-class dad.

|

| Samantha and her intrepid mother. |

Unfortunately, Christa’s battery didn’t have the poles clearly marked. Reversing the polarity is dangerous for both the cars and the people making the mistake, so, while I had an idea, I don’t like guessing. I called my husband and asked him to search for a diagram on the internet. Meanwhile, Chrissy paged logically through the owner’s manual.

“How to charge a dead battery, page 173,” she read. There was the picture we needed. We were so charged up—ahem—by our success that we stopped in Lake Placid and figured out the slow leak in Chrissy’s tire.

|

| There is nothing so fine as an outdoor shower. |

I drove back to my cabin and had a late-night outdoor shower. An unknown creature was baying and the rain hitting the roof lulled me to sleep. Who cares if I’ve forgotten how to paint? This is heaven.