When do you get to stop worrying about your kids? Never.

I’ve had an exhausting fortnight, as my British subjects would say. I arrived in Albany, NY from my western perambulations with just enough time to alter multiple outfits for my goddaughter’s wedding. That was in Rochester, NY, last weekend. A lovely time it was, too. When my third daughter started to complain of abdominal pain, she pounded acetaminophen rather than set aside her bridesmaid’s duties.

She wasn’t kidding that it hurt; she had an emergency stent put in on Tuesday and her gallbladder removed on Wednesday. I’m vastly relieved that as of this writing she sounds much more chipper.

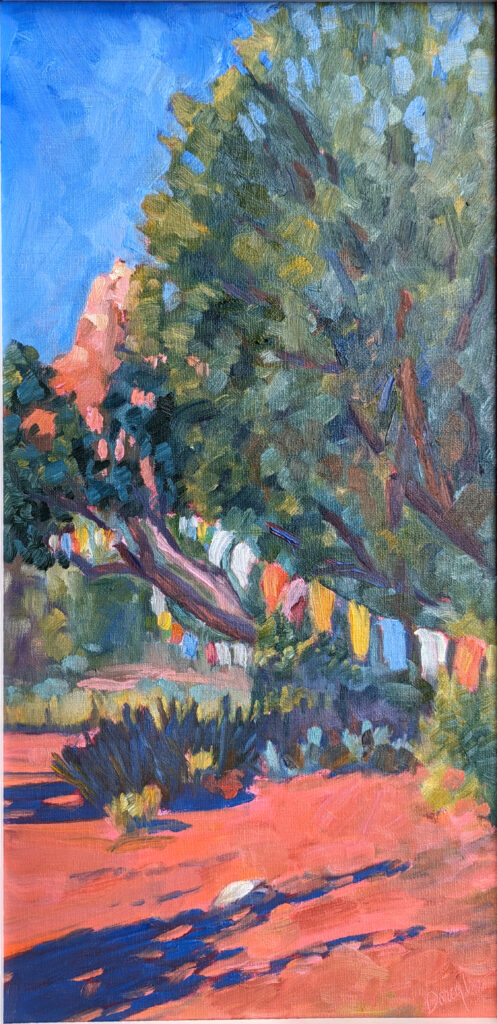

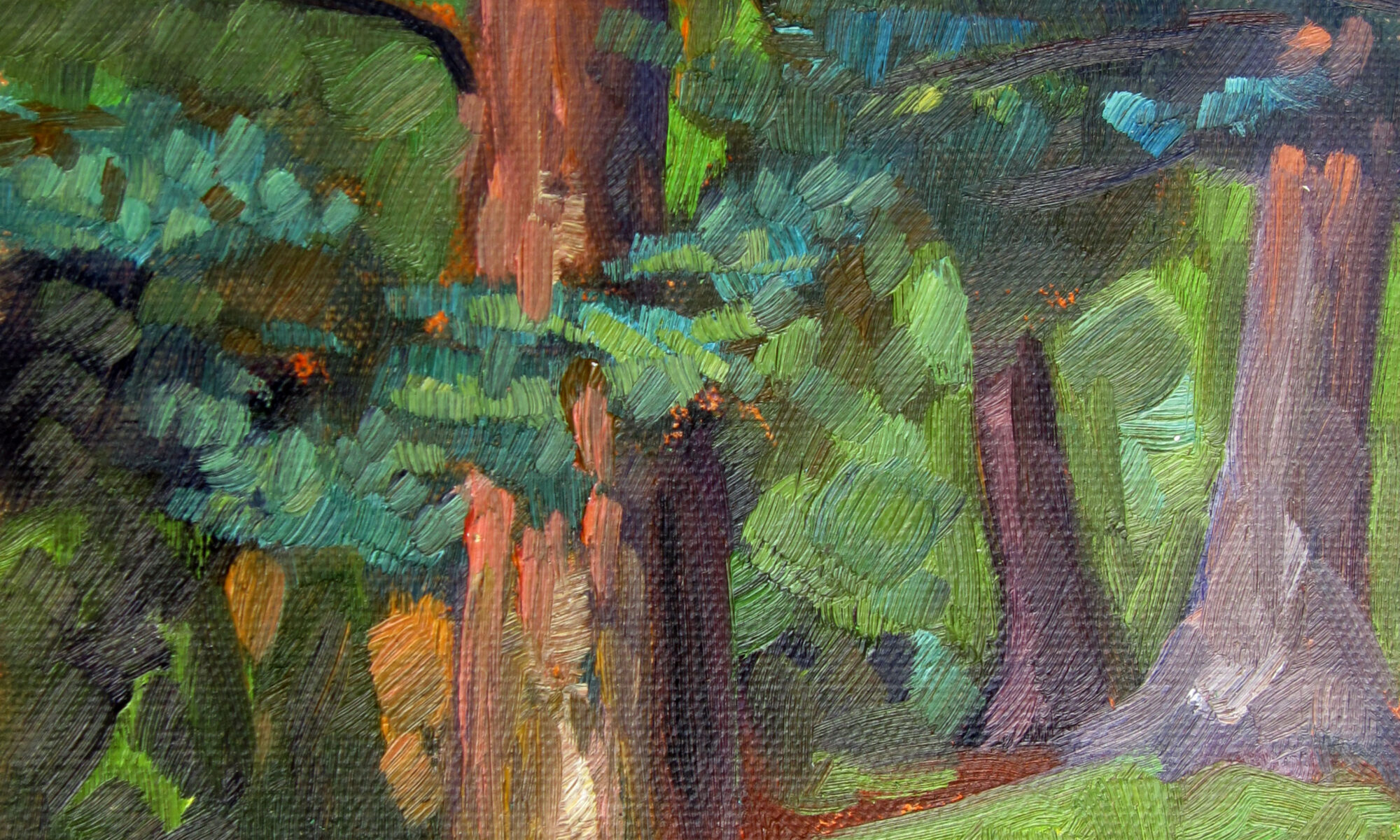

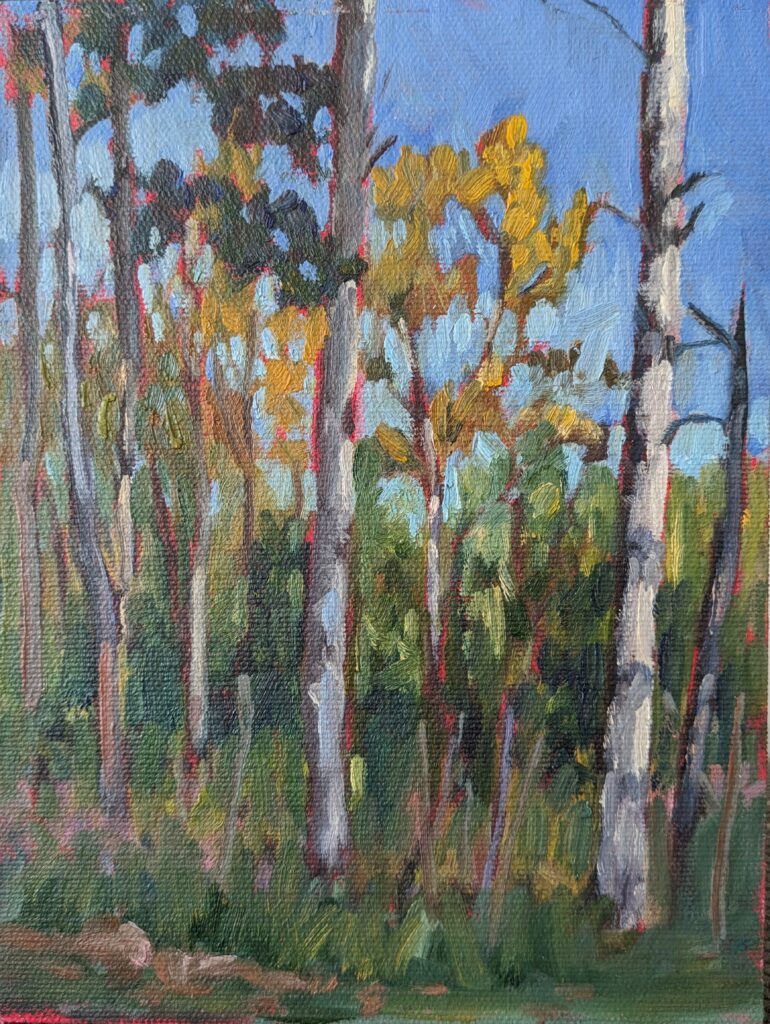

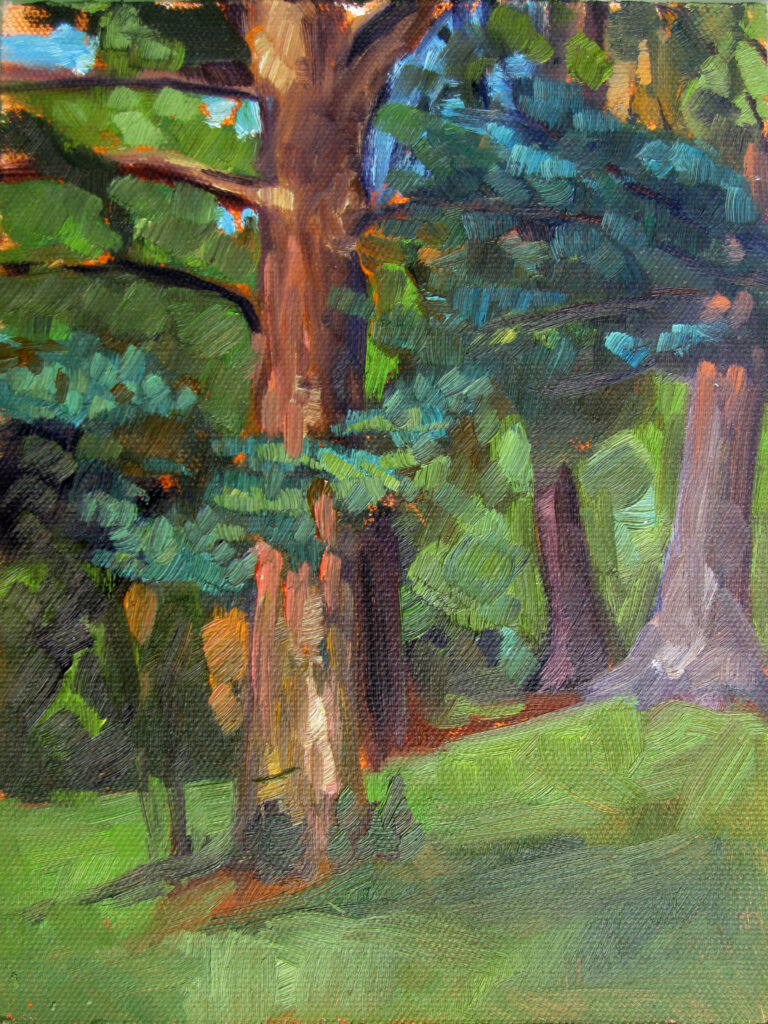

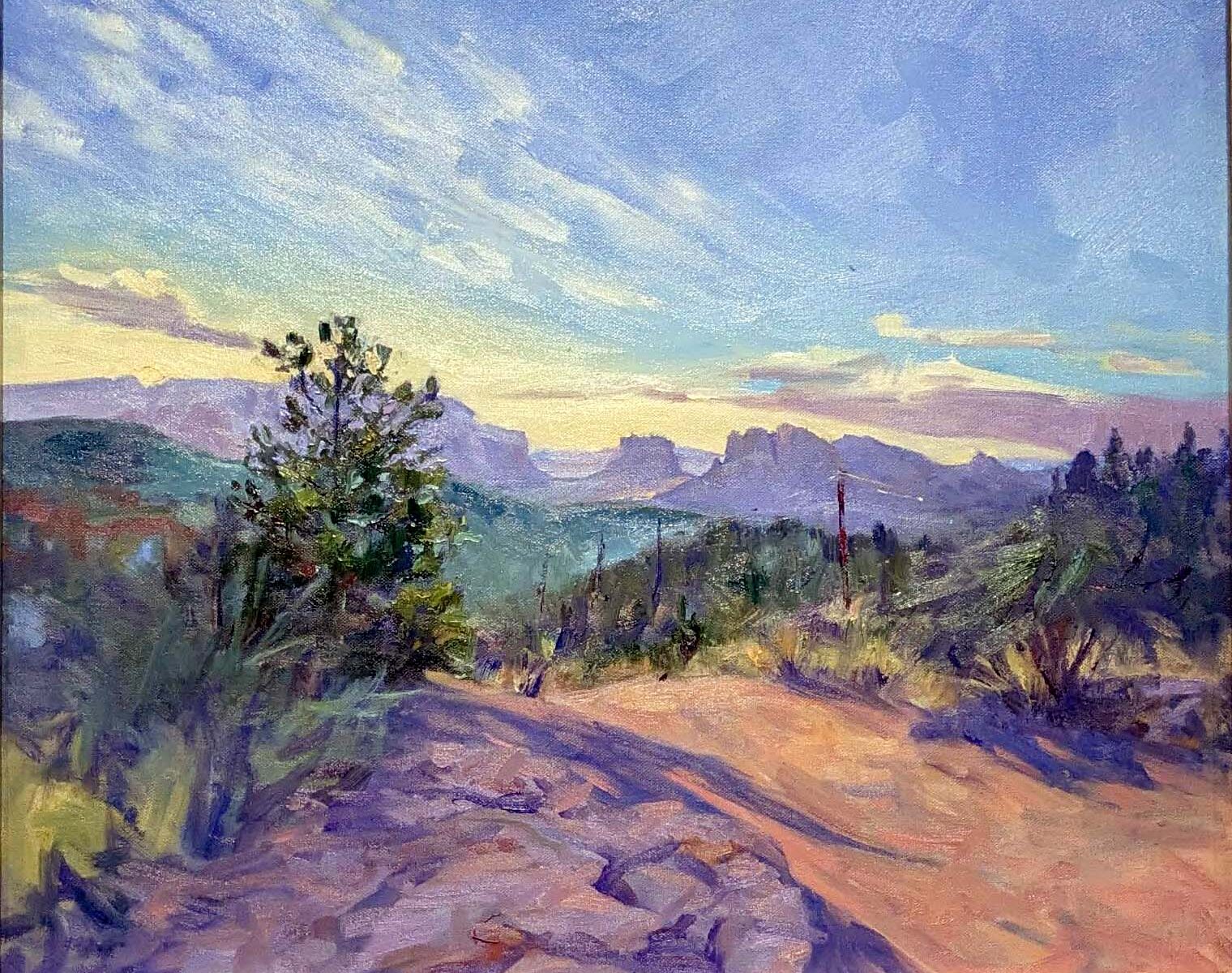

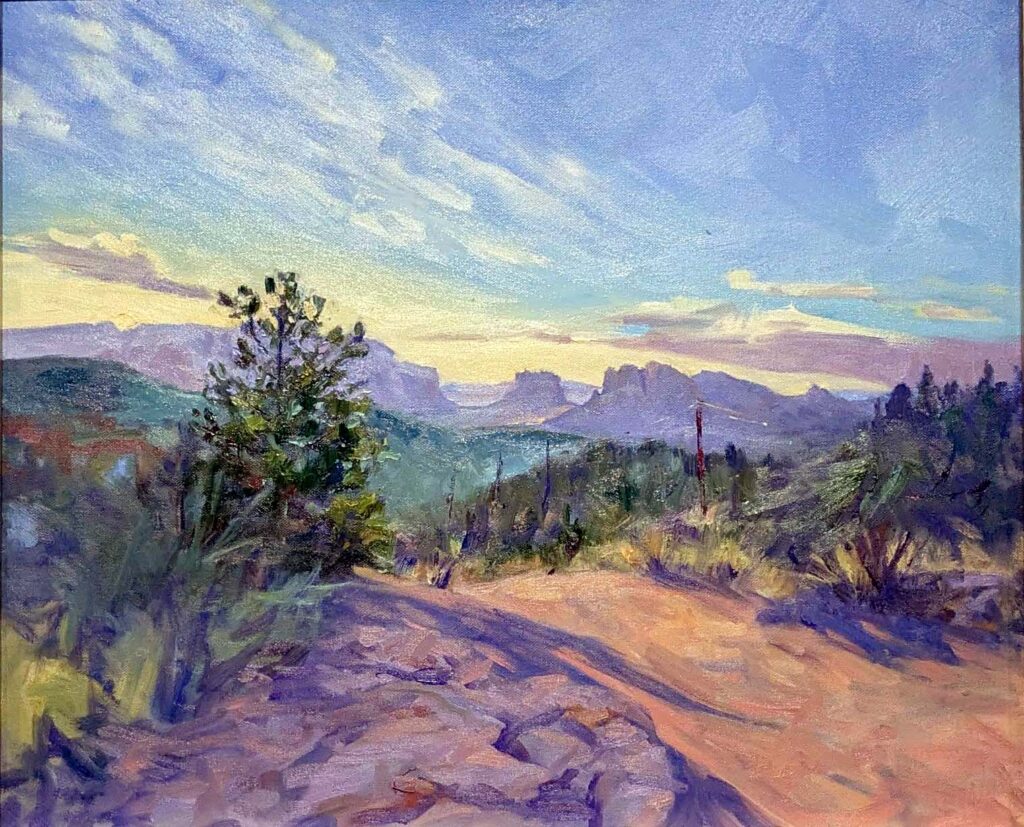

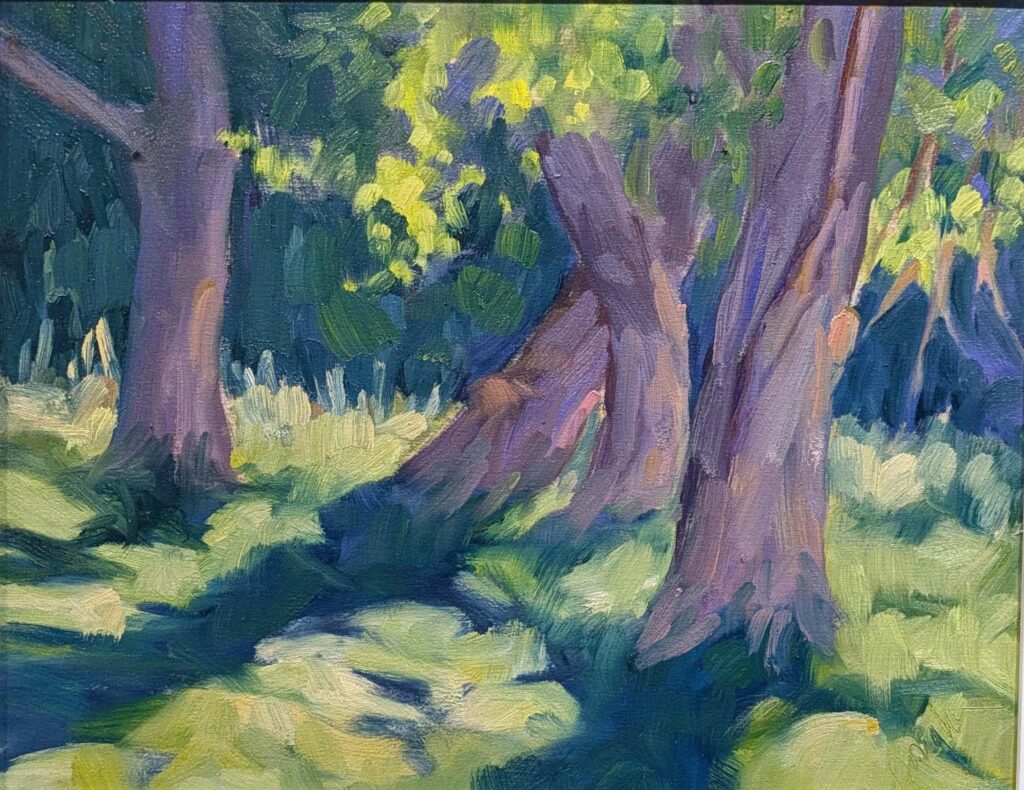

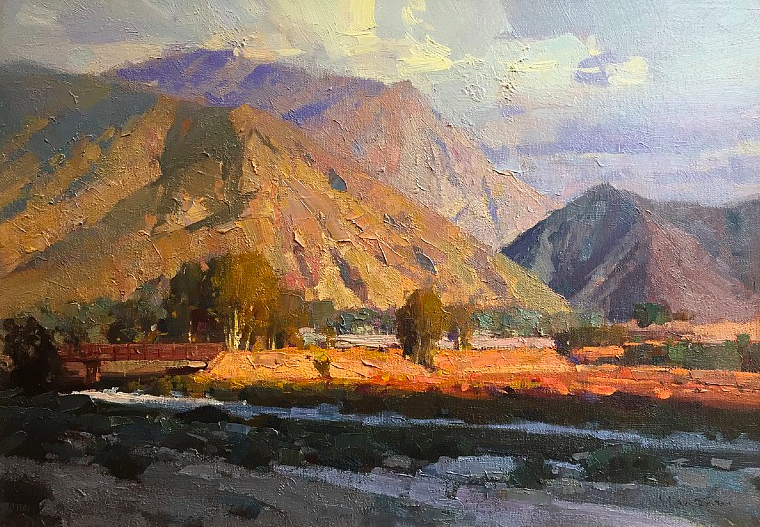

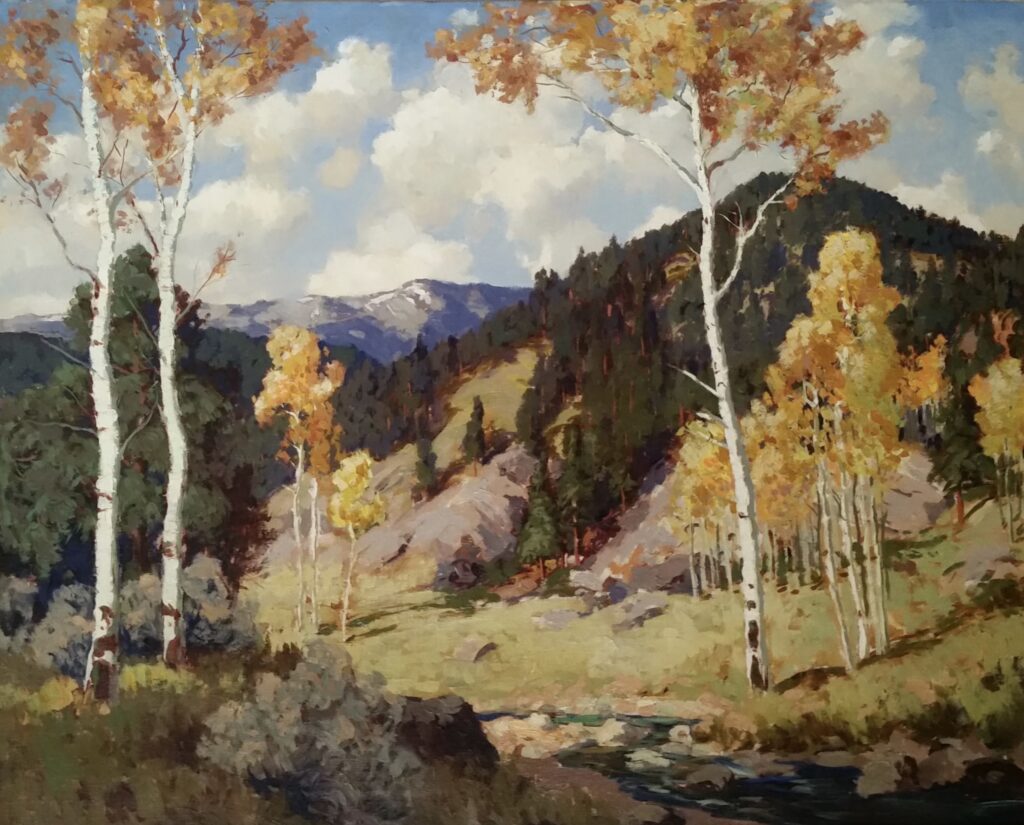

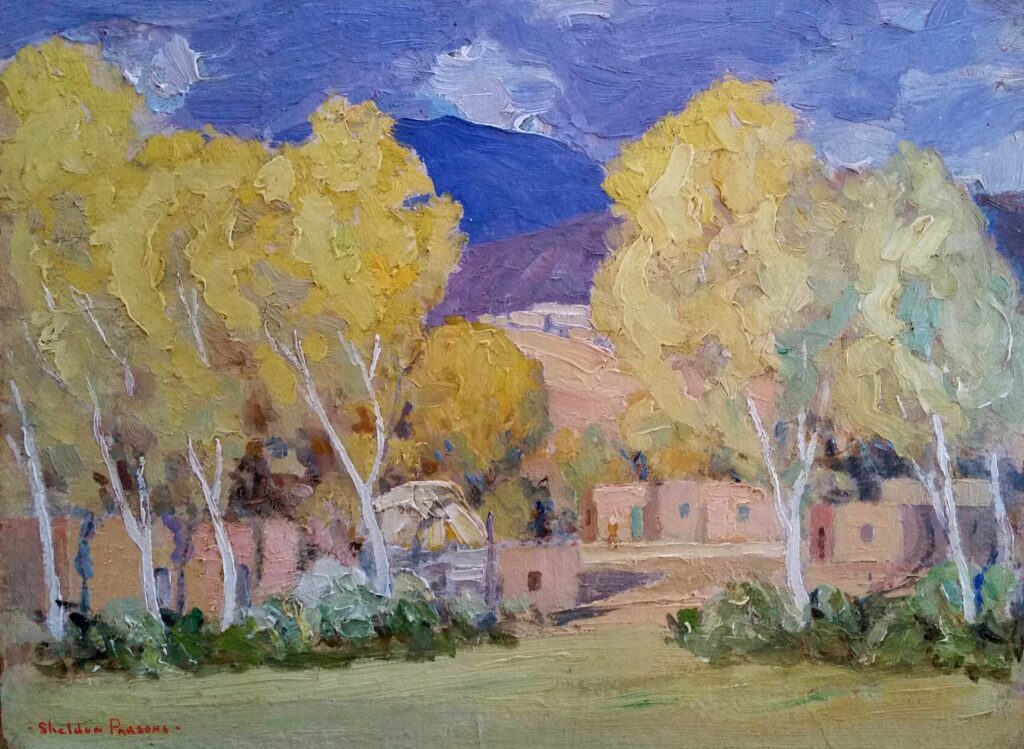

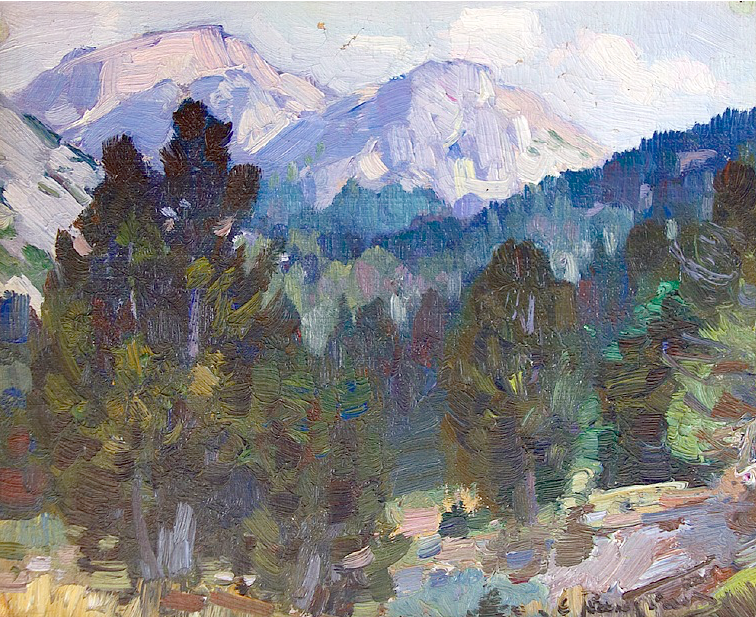

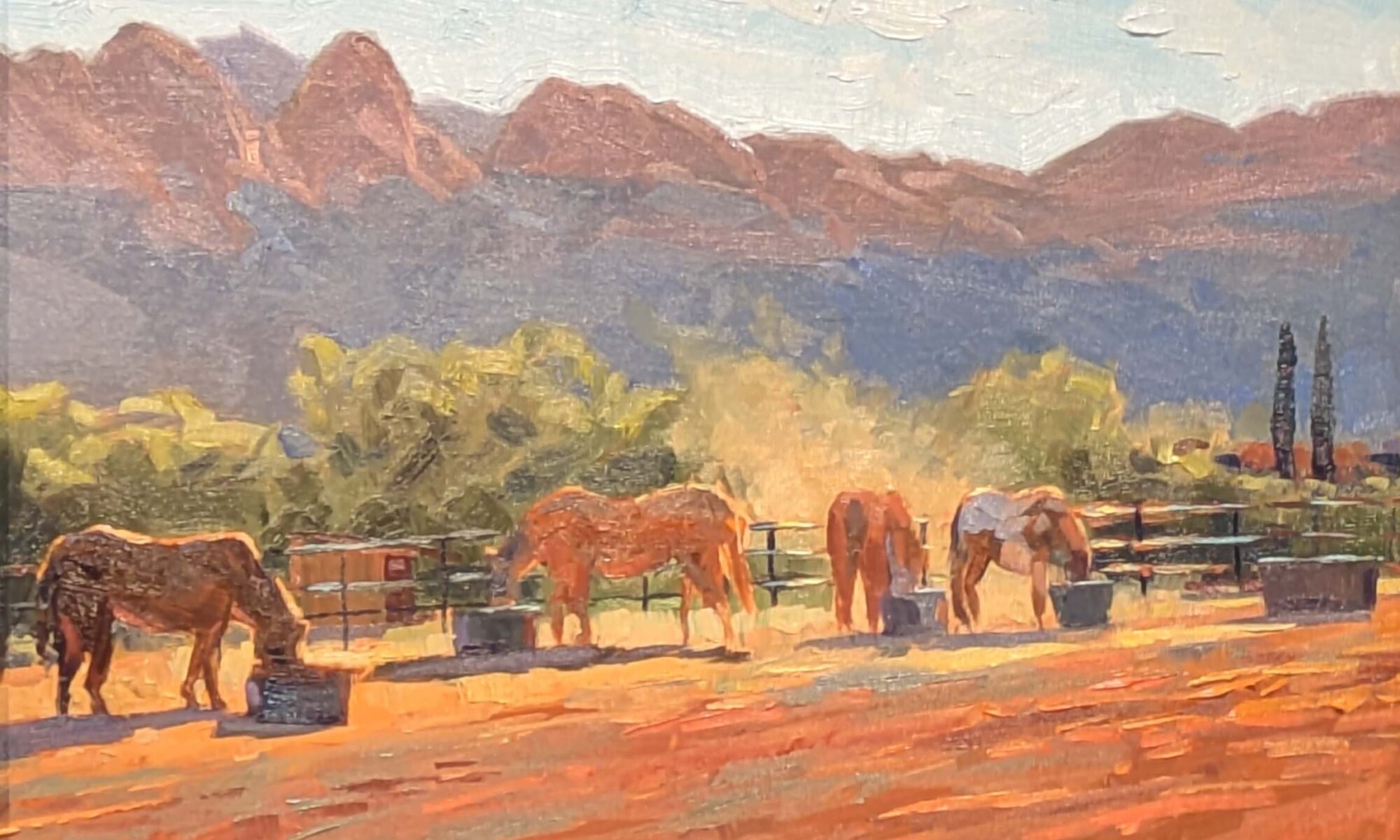

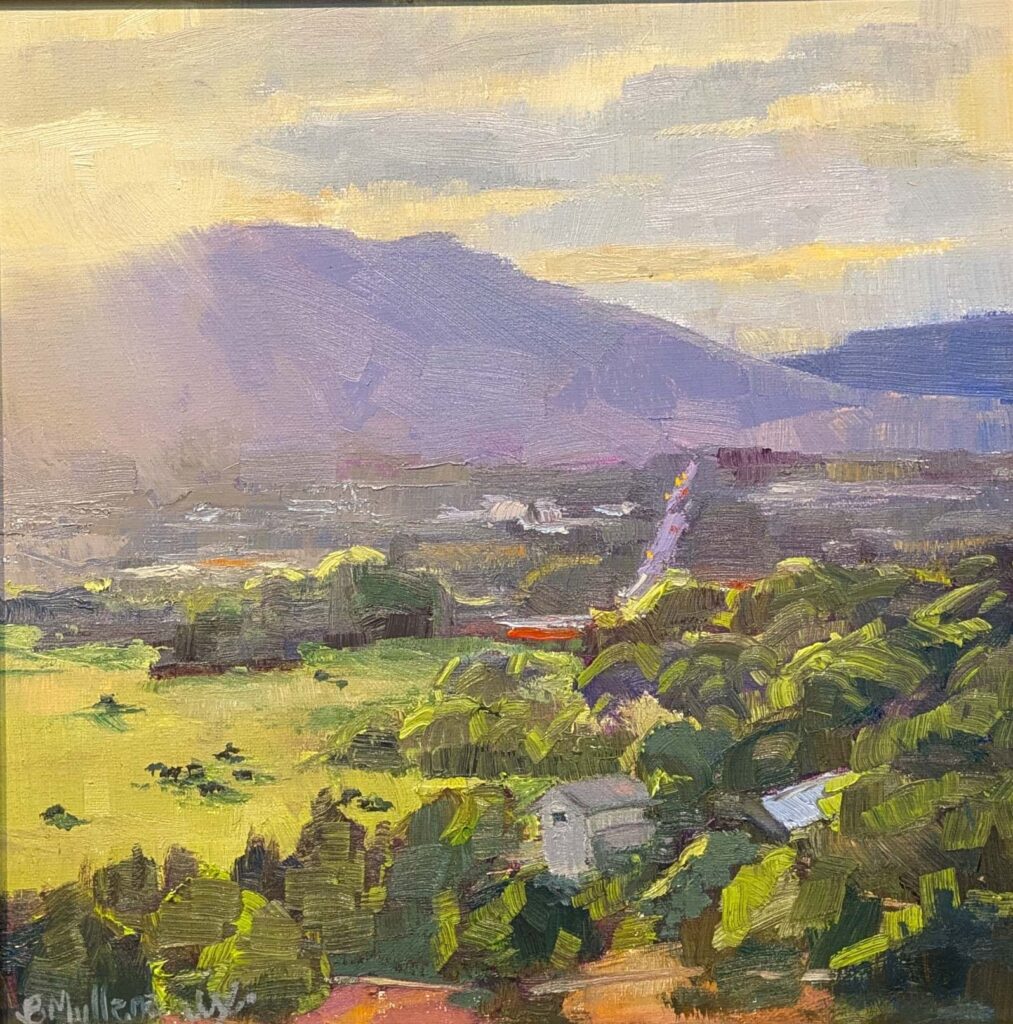

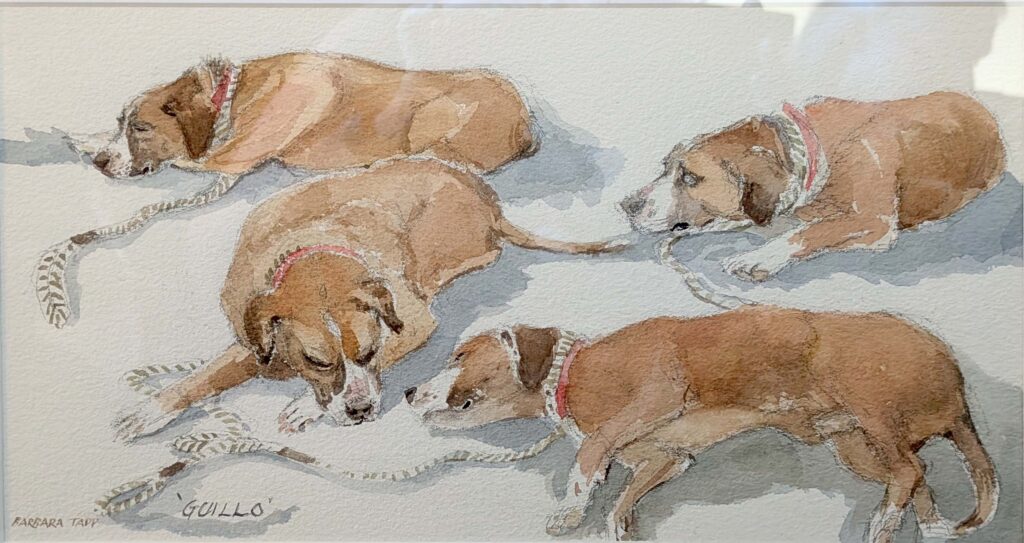

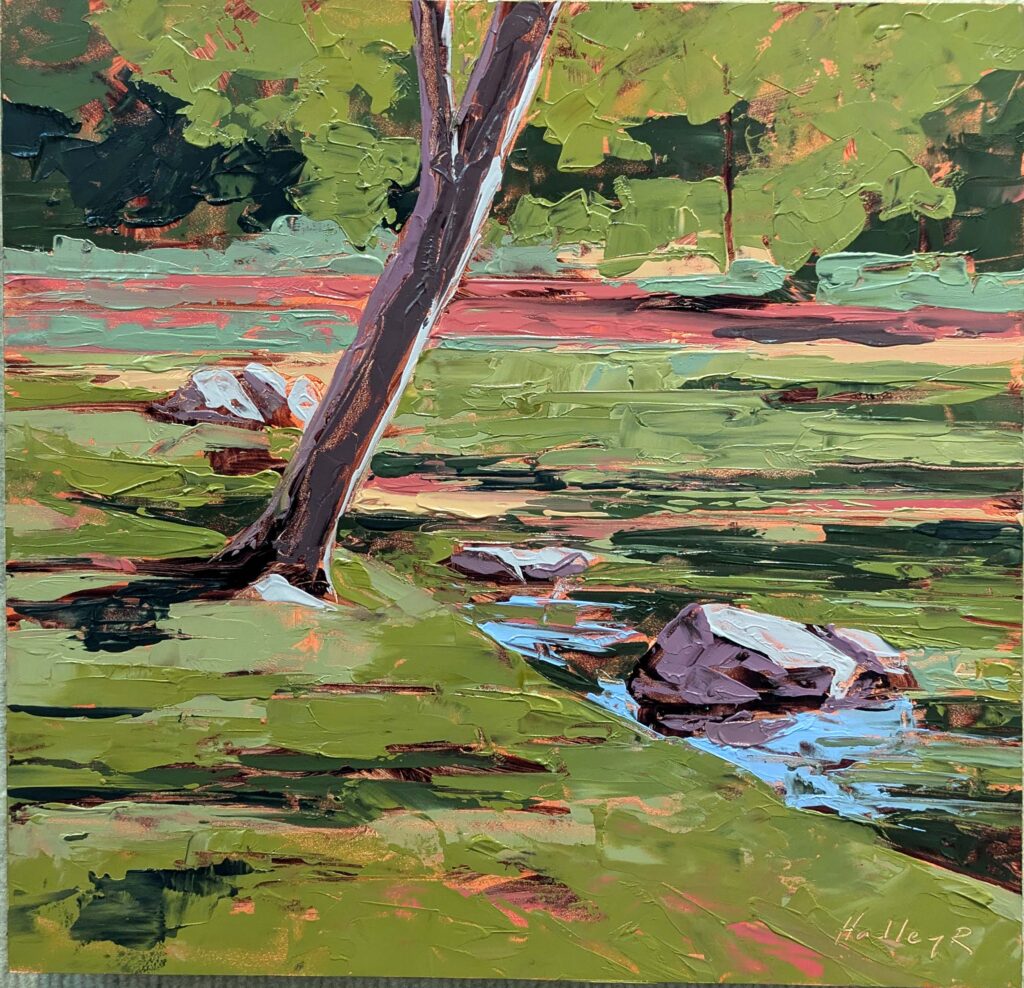

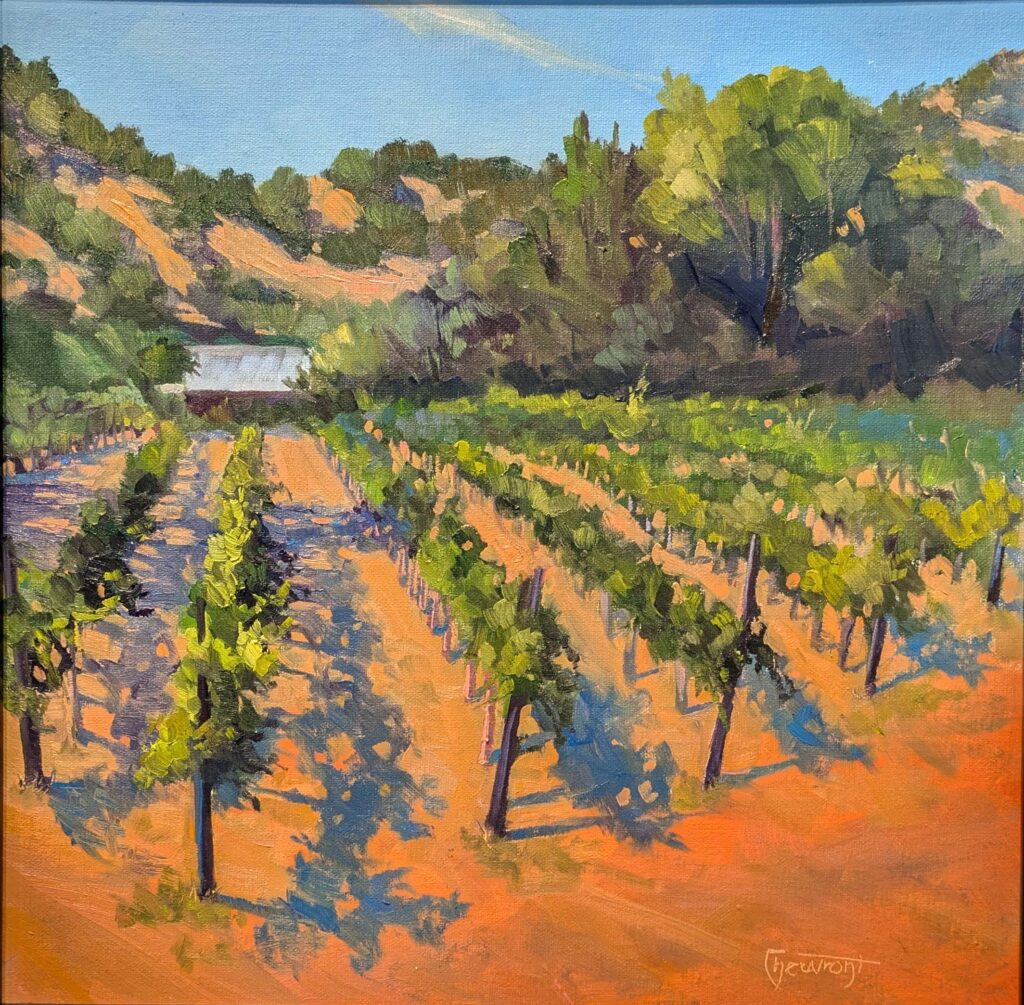

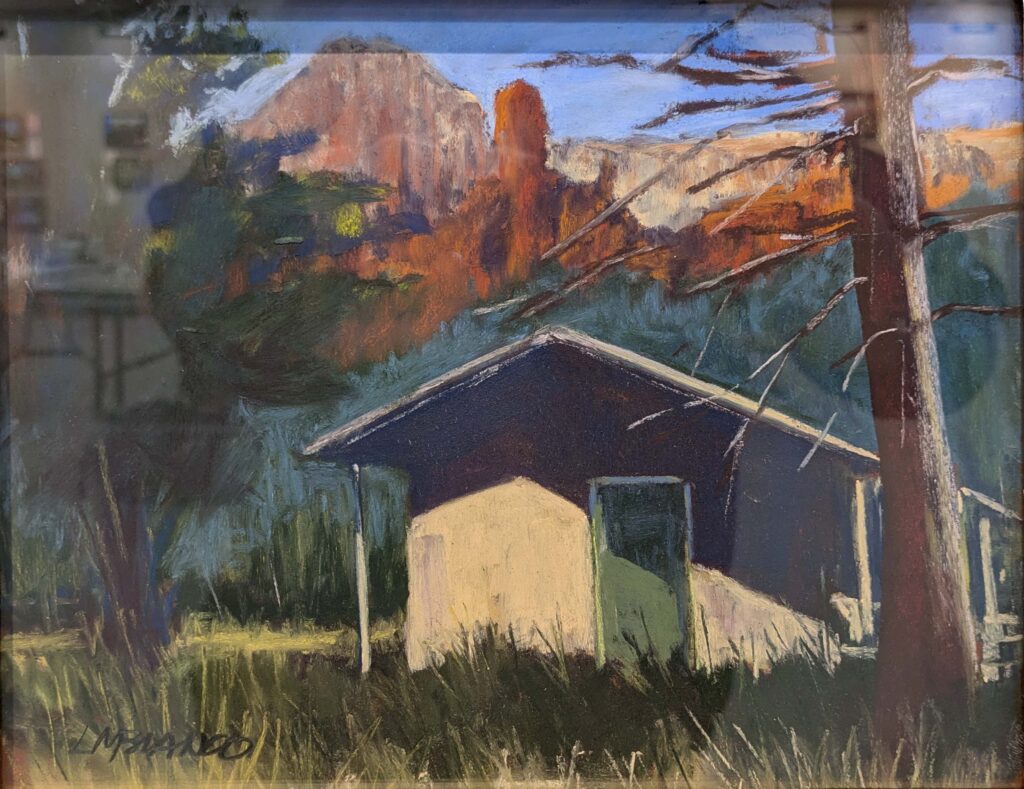

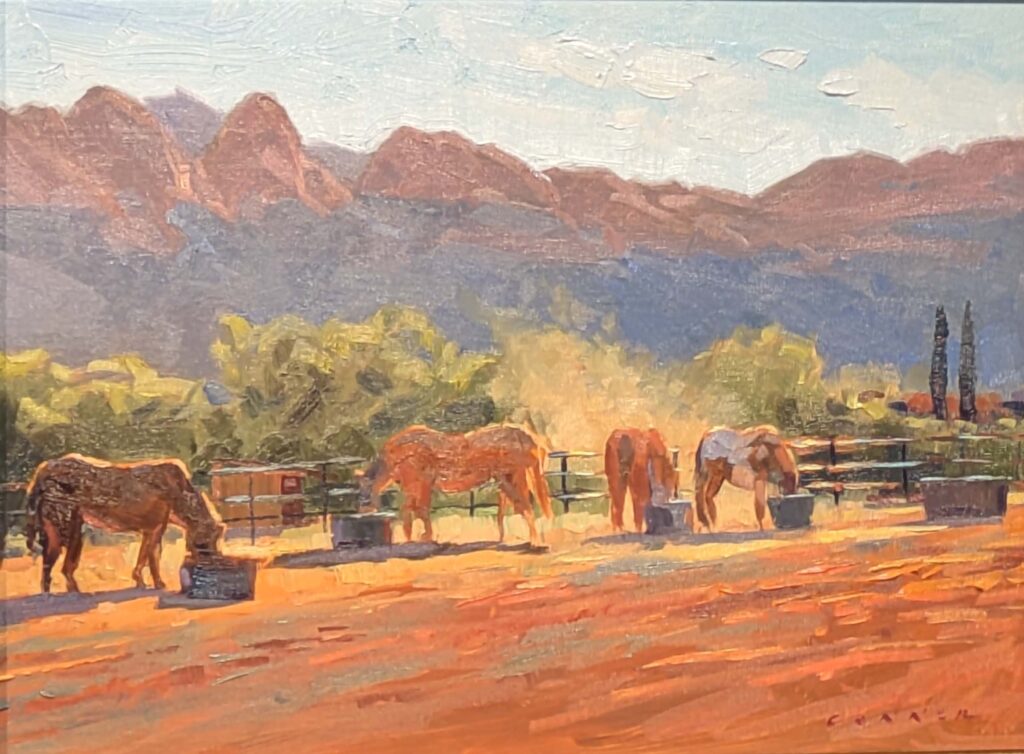

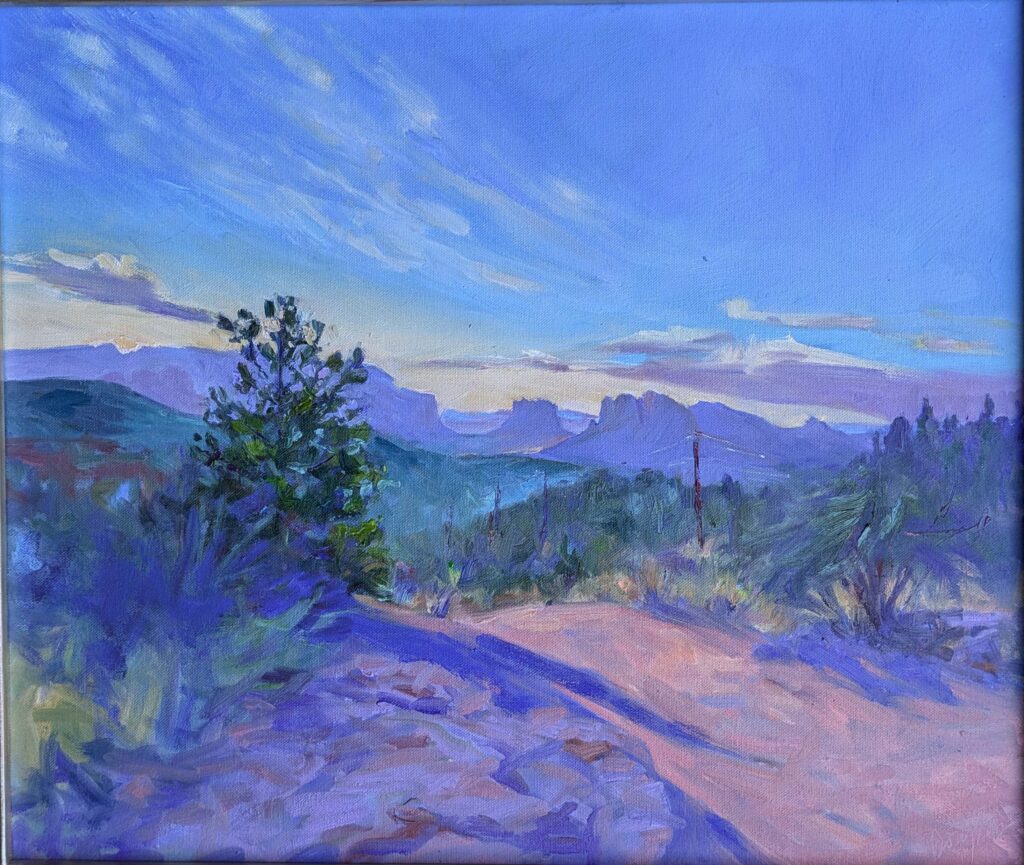

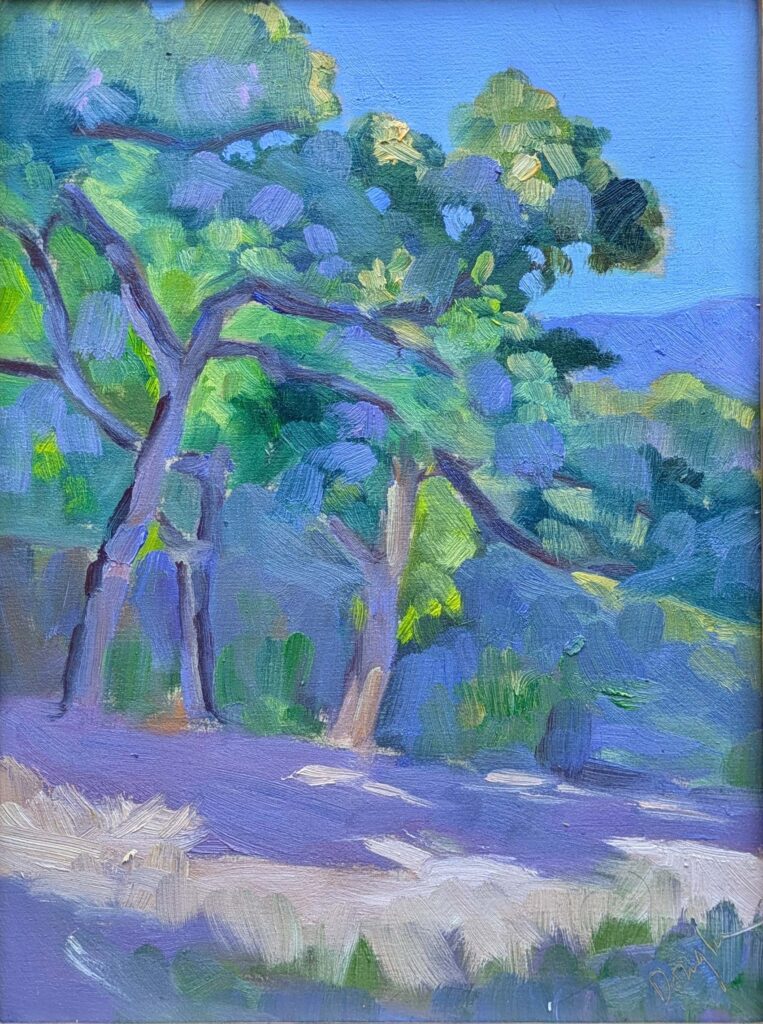

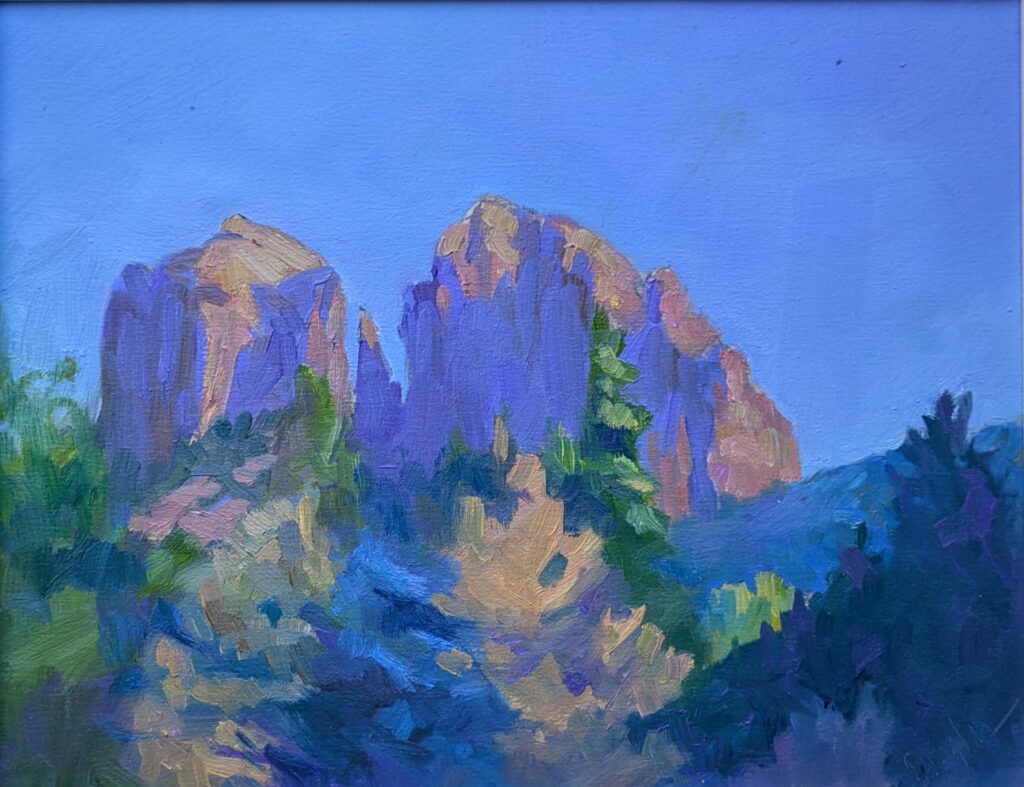

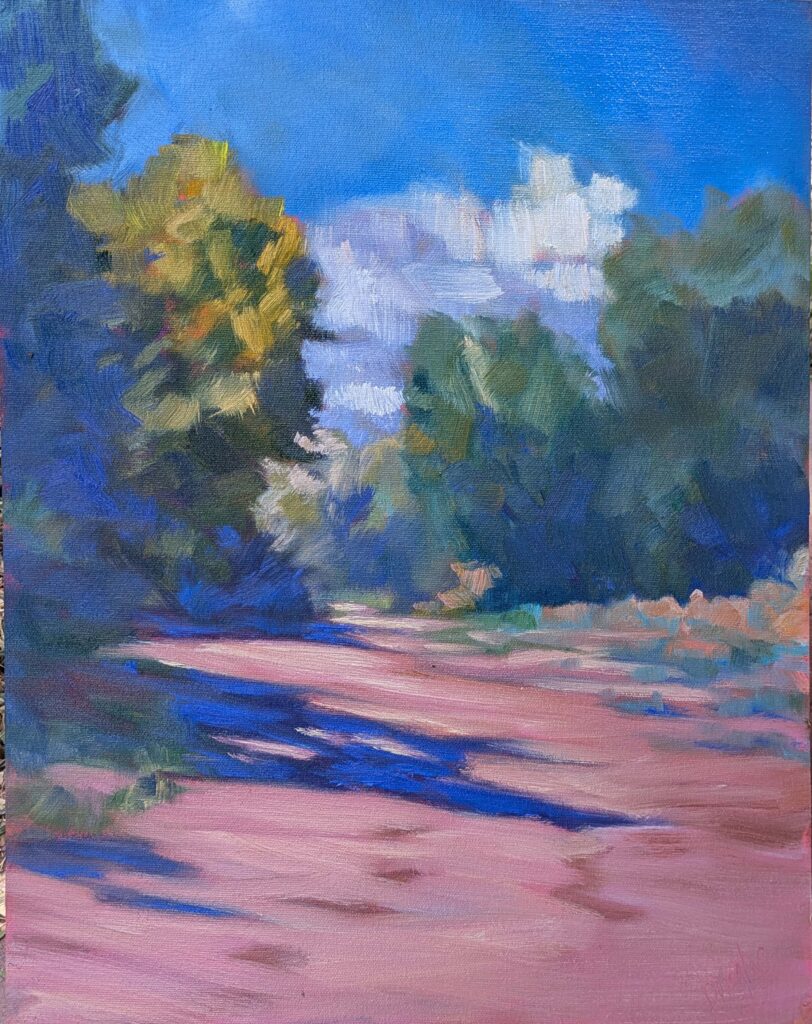

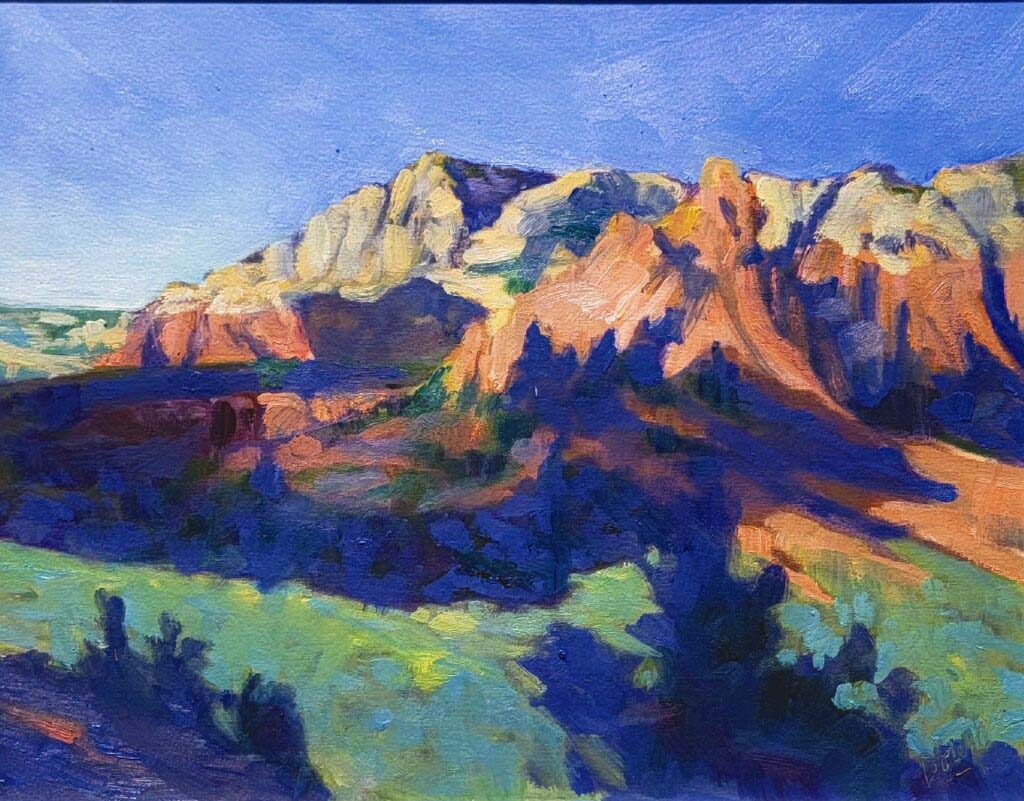

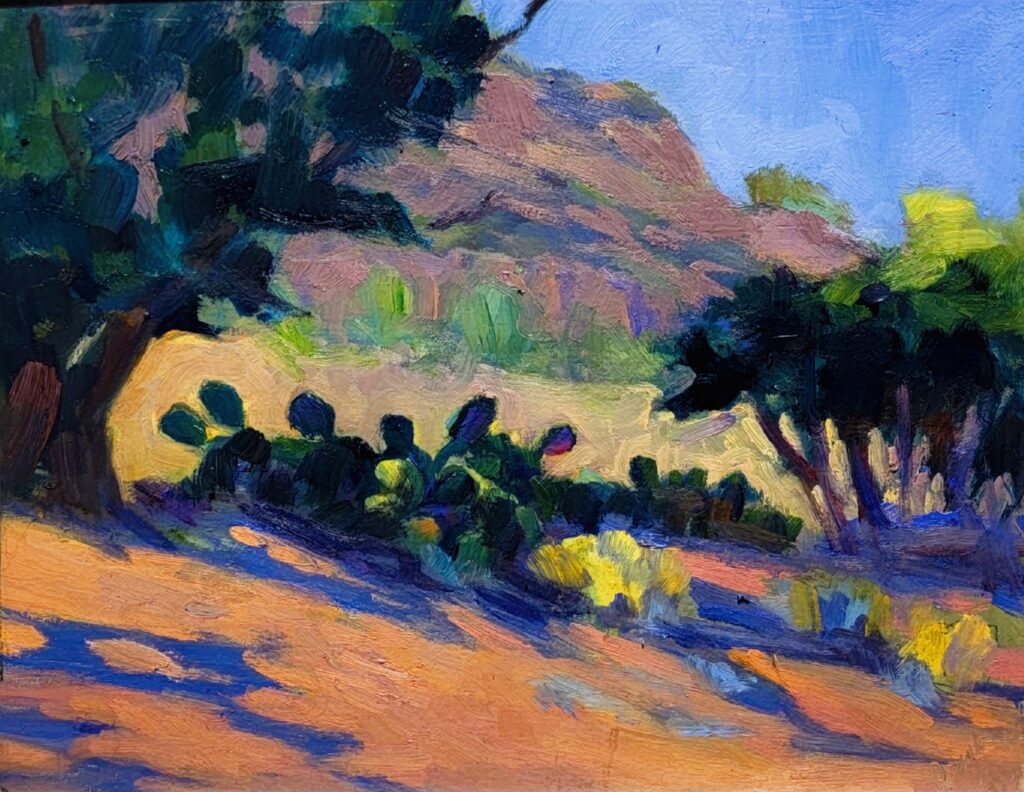

My work from this year’s Sedona Plein Air

I took terrible photos of my paintings from Sedona but (for some reason) it took me until yesterday to rephotograph the ones I brought home with me. Although I will make more money if you buy a painting directly from my website, I’ll be just as happy if you buy one from the Sedona Arts Center if that’s the one that trips your trigger; it’s a great organization and could use the support. To that end, I’ve separated them into two sections. Click on the image and it will take you directly through to more complete description.

As I was writing this post, I kept thinking, “That’s one of my favorite paintings.” That’s a good sign; it means I have nothing to apologize for.

On my website

Dawn, at top, and Cottonwoods along the Rio Verde, above, are both on my website. In addition, there are:

Through Sedona Arts Center

The photos on the Sedona Arts Center website are dark; I’ve replaced them with my file photos where possible. If you want further pictures showing the paintings in daylight or details, contact JD Jensen.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.