“I was looking at a friend’s IG post,” a reader told me. “I thought, ’She’s been painting for at least 35 years and nothing has changed or improved.’”

Another reader expressed his own frustration at being stuck. “Maybe to get better, we have to get tougher on each other at our paint-outs.”

As I’ve written repeatedly, severity is a terrible idea; positive feedback teaches more effectively than harsh criticism. Still, there are proven ways to stop paddling frantically in one place.

Why paintings fail

Most paintings fail because they aren’t thought out properly from the beginning. We don’t take time to ask ourselves important questions, like:

- What is the underlying idea?

- What am I bringing to the scene to raise it out of the ordinary?

- Where is the charm of this image and how will I express it?

- What is the overriding emotional state I want to represent (serenity, humor, angst, larkiness, etc.)

- What is the light structure and how can I use it as compositional adhesive?

- Where am I willing to riff on reality, and where does faithful rendering make sense?

- Most importantly, why am I bothering to paint this?

If you can articulate your motivation in one or two sentences, you’re already ahead of the pack.

Ability vs. humility

When I was fourteen, I believed that I was uniquely talented. I’m disabused of that notion today; there are many people out there with as much native ability as me. Many of us never allow ourselves to fail because we can’t risk exposing that little kernel of ego and insecurity in the public square.

Humility is the starting point of learning. That means trying and failing and then trying again, and listening to expert advice, especially when you’re paying for it.

I occasionally have students who preface all reactions with, “I know, but…” It’s a highly defensive response and hinders growth.

I have a regular correspondent who frustrates me because I know he would benefit from another workshop. However, he thinks that because he’s taken one, he ‘knows what I teach.’ (If that’s true, he’s not putting it into practice.) He would improve, not just from hearing it again from me, but from rubbing shoulders with others bent on improvement.

Iron sharpens iron

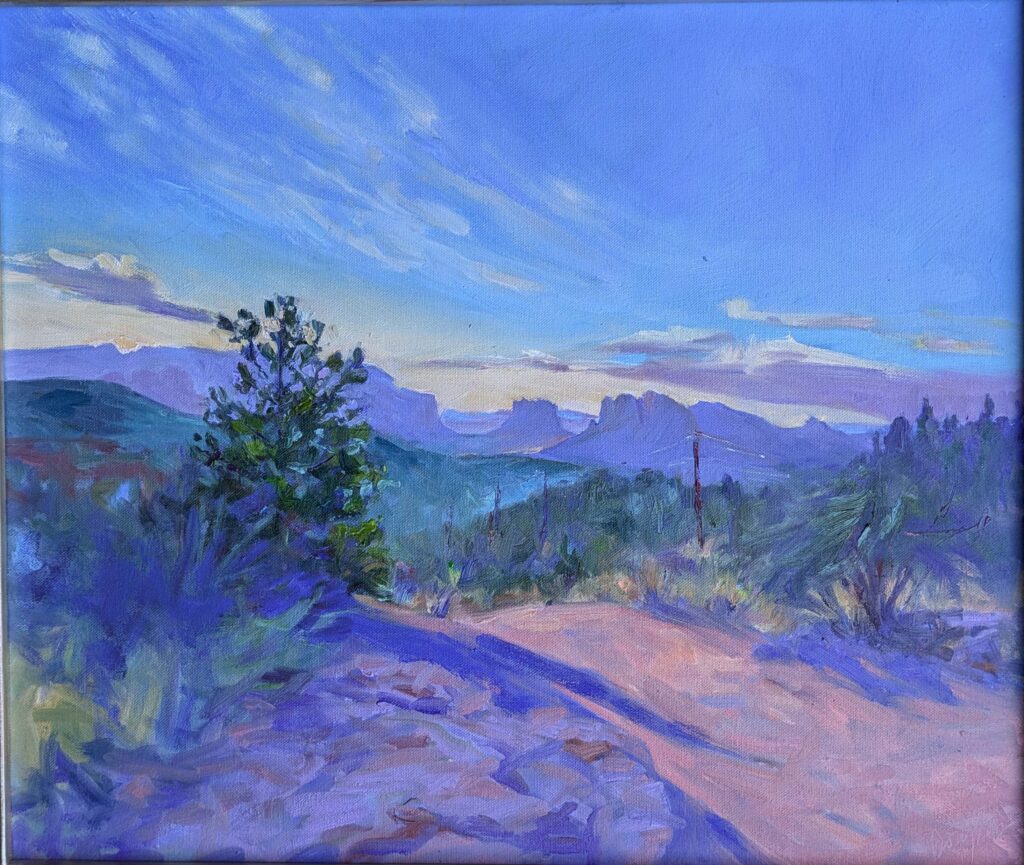

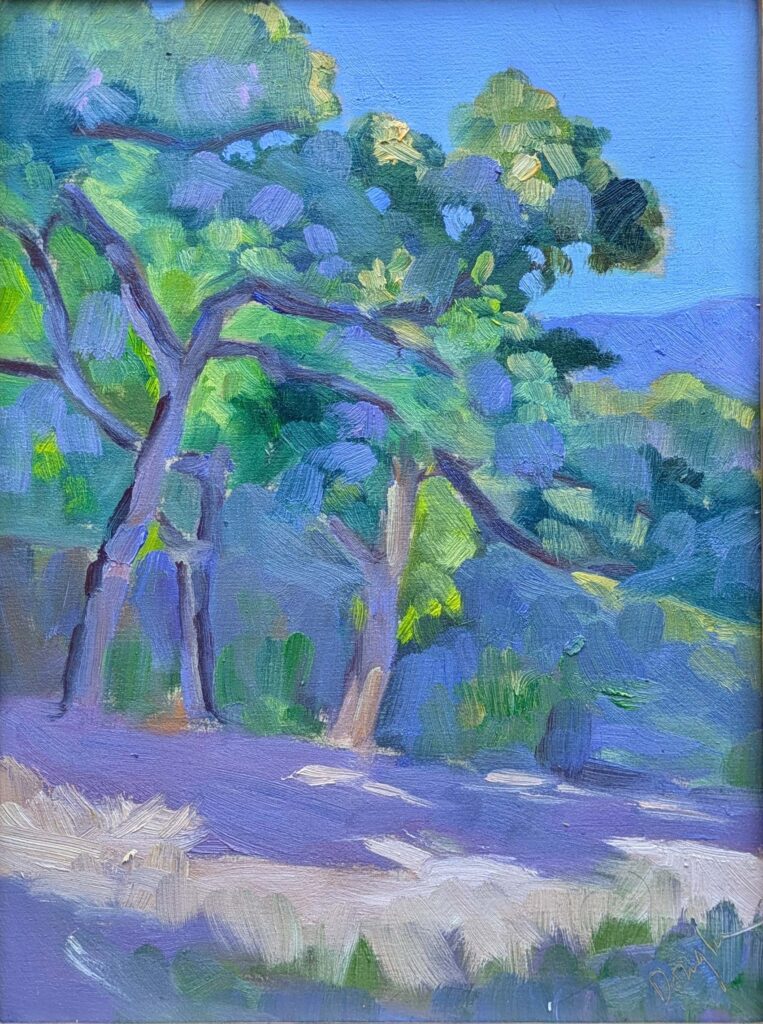

I am not able to paint right now (see Wednesday’s post) and I won’t be teaching until the beginning of the year. I miss teaching as much as I miss painting. I learn a great deal from my students, and they prevent me from getting rusty during periods when other things get in the way of my brush time.

Improvement rests on the following principles

- Regular practice. Set aside time to work, even if it’s just a few hours a week. The more you practice, the better you’ll get.

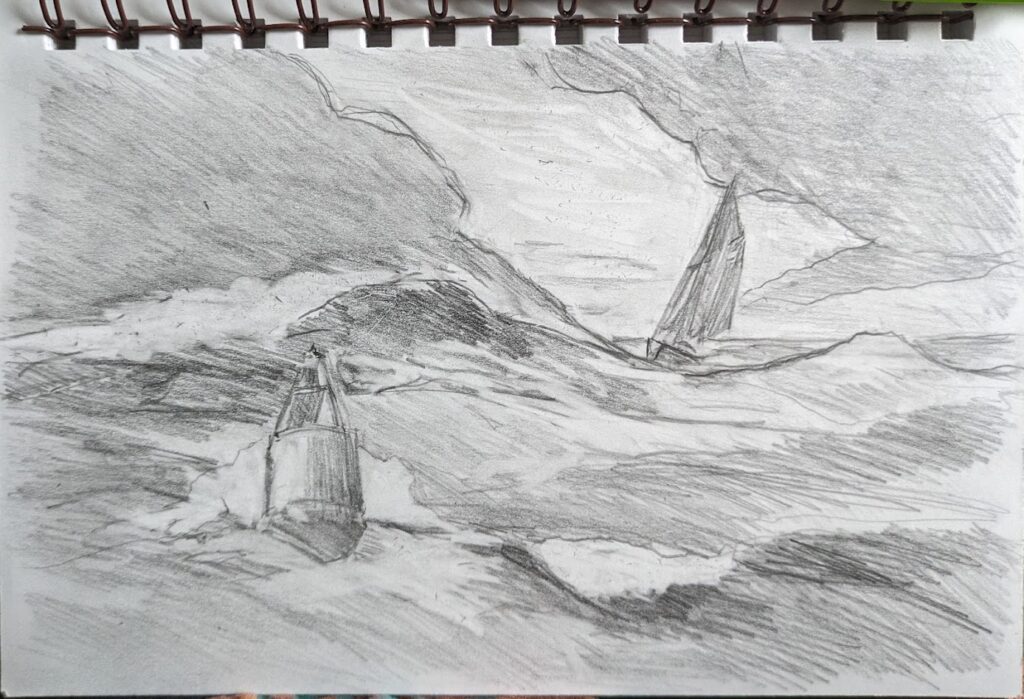

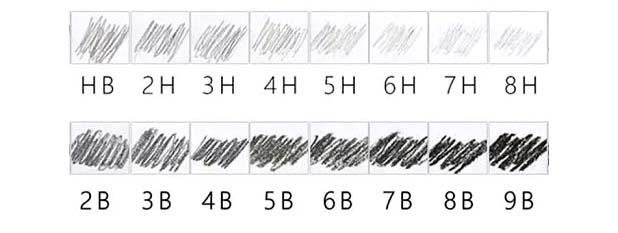

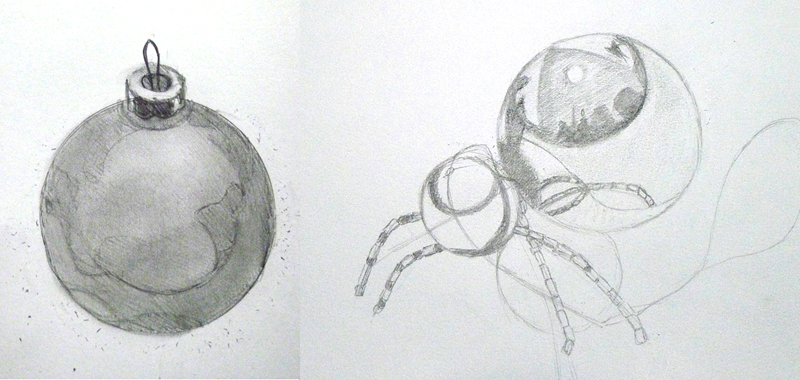

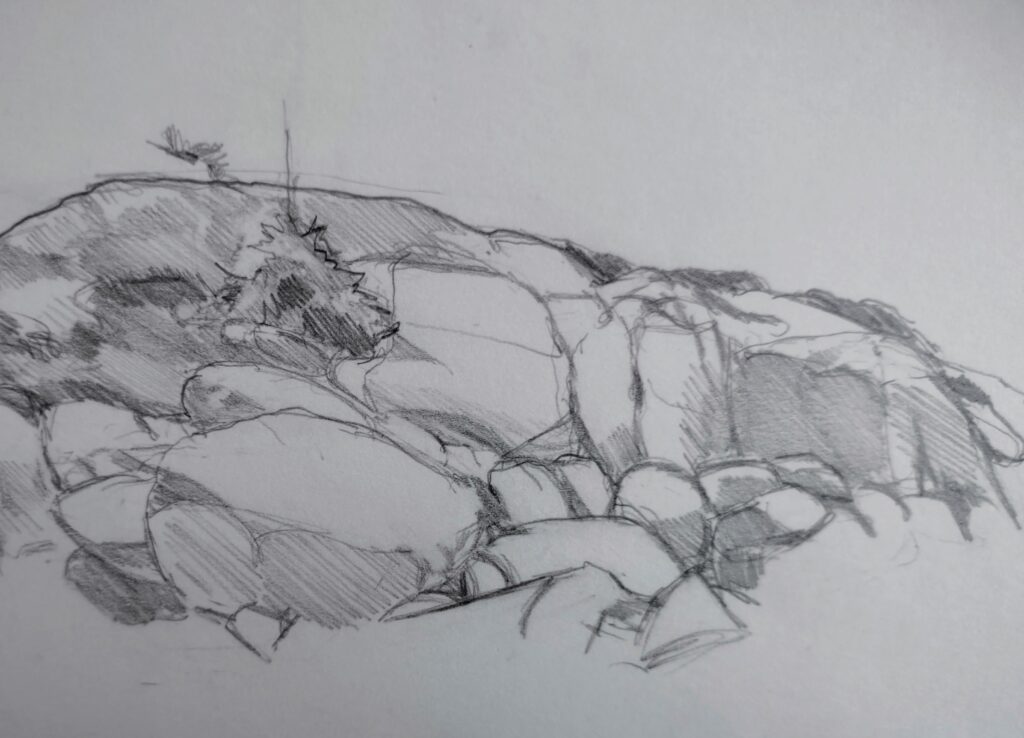

- Study the basics, which include color theory, optics, drawing, brushwork, and the elements of design.

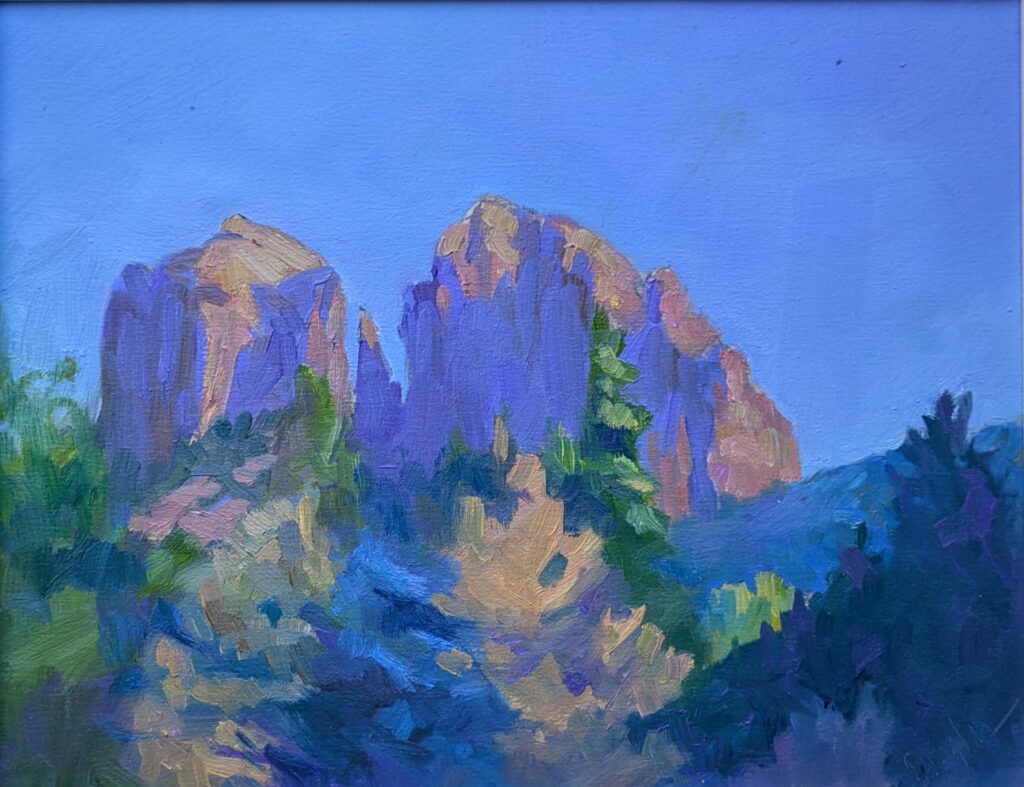

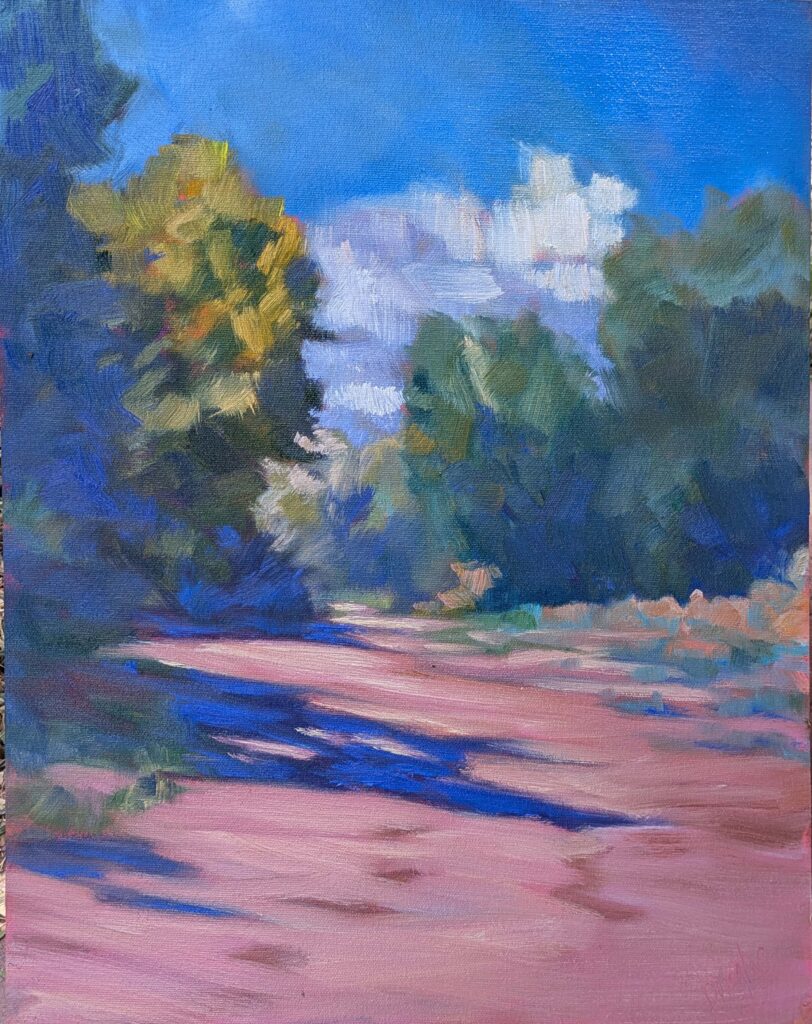

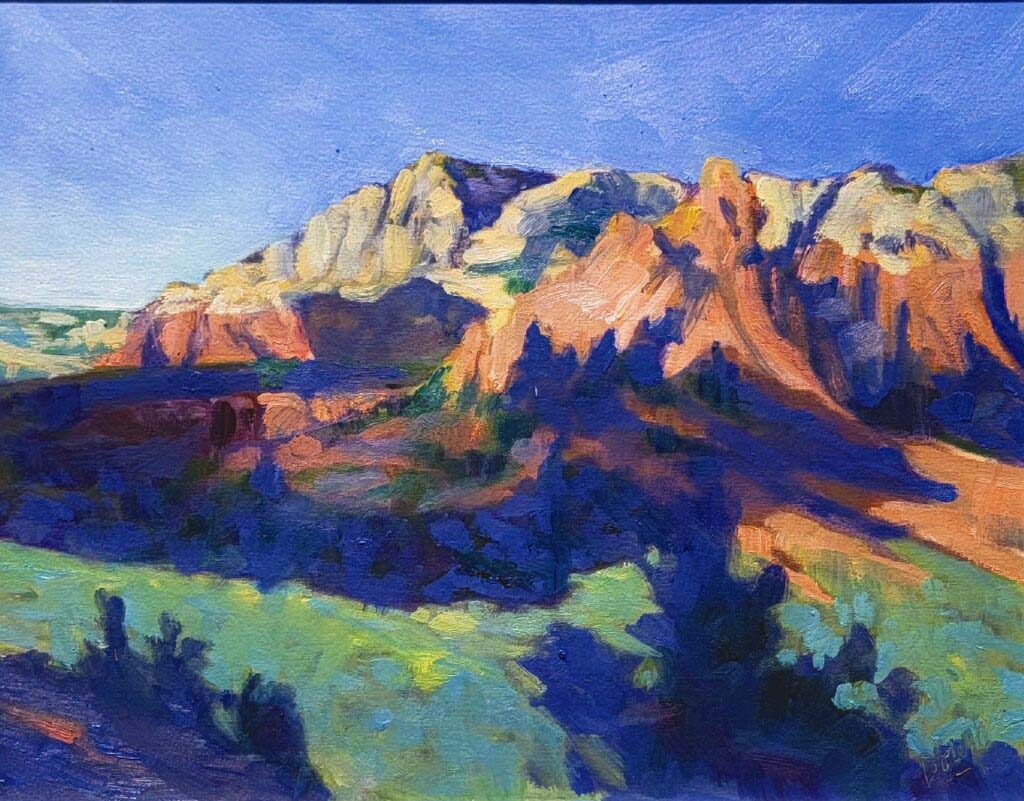

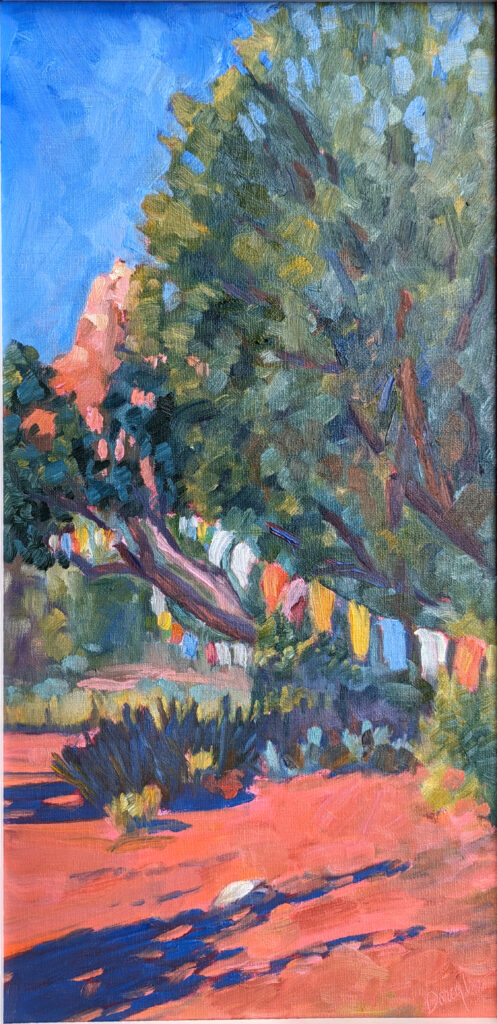

- Study the masters and other contemporary painters.

- Continue to take classes and workshops.

- Be willing to innovate; don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

- Have fun. If you’re not enjoying painting, what’s the point?

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.