“Fifteen years from today, your income will be within 10% to 15% of the average of your 10 closest friends’ income,” financial advisor Dave Ramsey wrote. He was drawing on a massive 2022 social-media study by Raj Chetty, et al, that showed economic connectedness to be the single greatest predictor of economic mobility.

Like so much data analysis, this study is built on assumptions that may be faulty. Still, the idea lines up with common sense. Anyone who’s spent time in the art world knows that it’s easier to get a Manhattan solo show when your closest friends are on the Upper East Side. Humans tend to dress like, drive like, and talk like their tribe. We’re herd animals, and group-norming is a powerful impulse. If it makes you work harder as an artist or strive to be more successful, that’s great, but group norming can also be a force for mediocrity or worse.

Energy vampires

There are people who suck energy out of the room. Ramsey calls them “energy vampires,” and advises us to tell ourselves, “The people that I spend time with that are negative are going to be limited to the amount of energy that I have to help them not be negative.”

Some of these situations are unavoidable: the person in a health crisis, the elderly neighbor who’s alone during the holidays. We’d be inhumane to ignore them. But some of them are like an annoying dripping faucet; we’re so accustomed to their carping that we don’t ever assess whether the relationship is healthy.

We presume that if we give selflessly, the other party always benefits. It’s sometimes surprising when your best efforts backfire or are misconstrued, but you may be actually harming that other person more than you’re helping.

Energy vampires are often drama queens. It’s painfully easy to get sucked into their battles; the classic model for that being “let’s you and him fight.”

Situational depression vs. energy vampires

We will all go through times in our life where we’re dealing with crisis or tragedy. Situationally-depressed people can mimic energy vampires, with the same narrow focus and worldview. It’s sometimes hard to tell the difference, but humanity requires that we treat our situationally-depressed friends with kindness.

This is a special problem for artists

I’ve been self-employed since 1990. The one universal truth of working from home is that people think you’re free to lavish time and attention on them. It’s true that our schedules give us flexibility, but all those demands grow like weeds and before we know it, we don’t have time to paint.

Many painters have a similar personality style to my own: fundamentally we’re introverted but we play extroverts in public. Most of us are intuitive, because that’s how art works. These traits make us vulnerable to manipulation.

Dealing with energy vampires

It’s important to remember that we’re not responsible for others’ emotional states. We need to set boundaries, either of time and space, or emotional barriers.

If you always feel drained, anxious, foggy, or stressed after spending time with a particular person or social group, that person may be an energy vampire. You don’t need to tolerate constant negativity. It gets in the way of your real work.

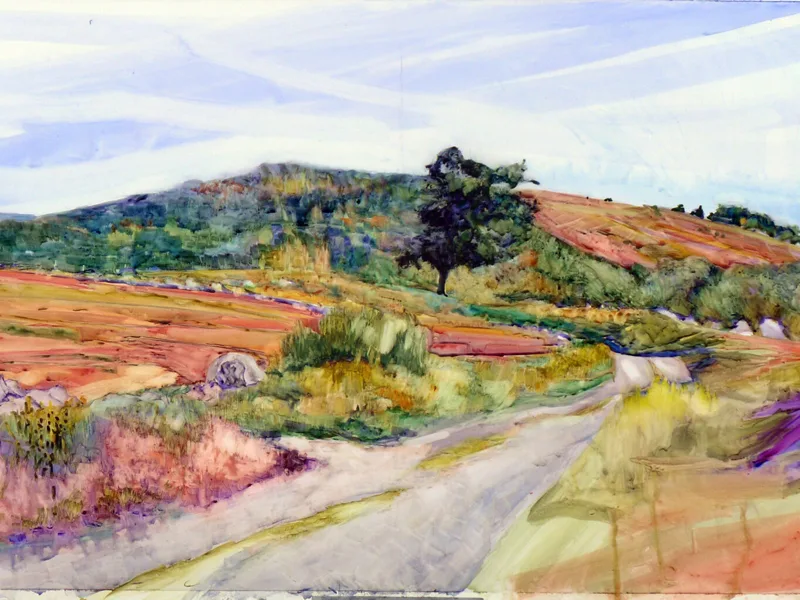

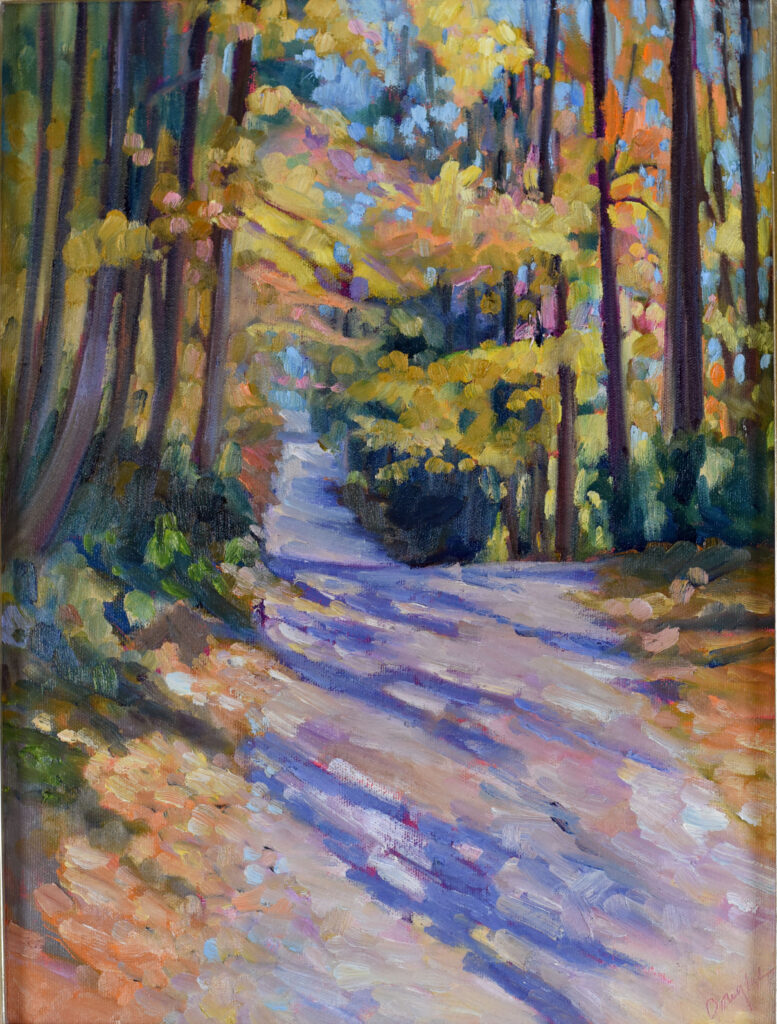

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

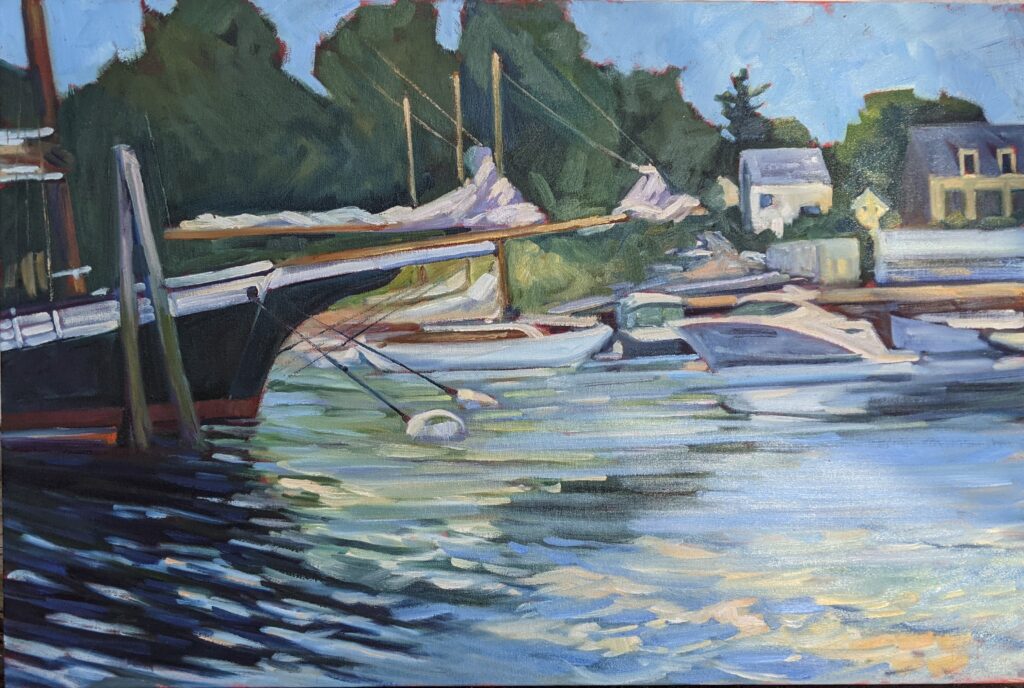

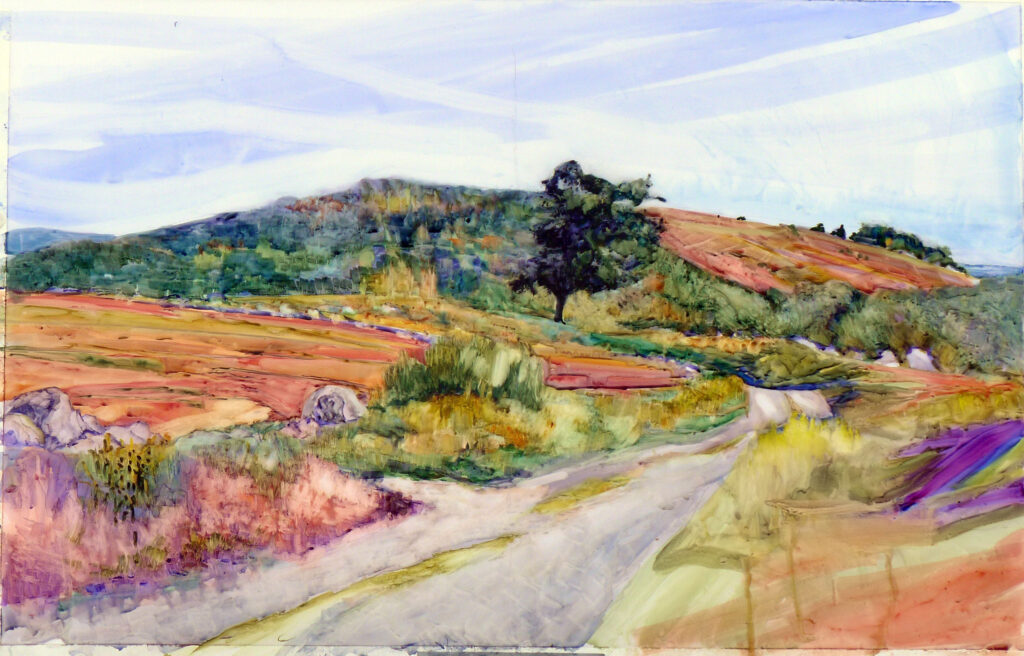

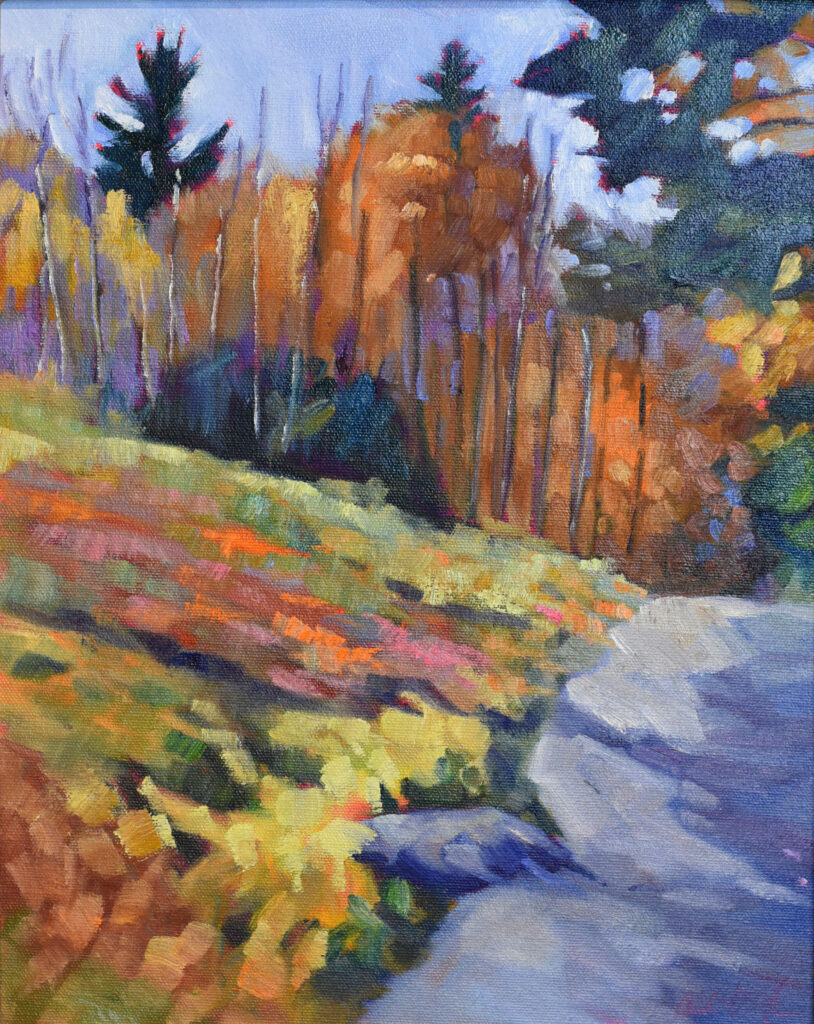

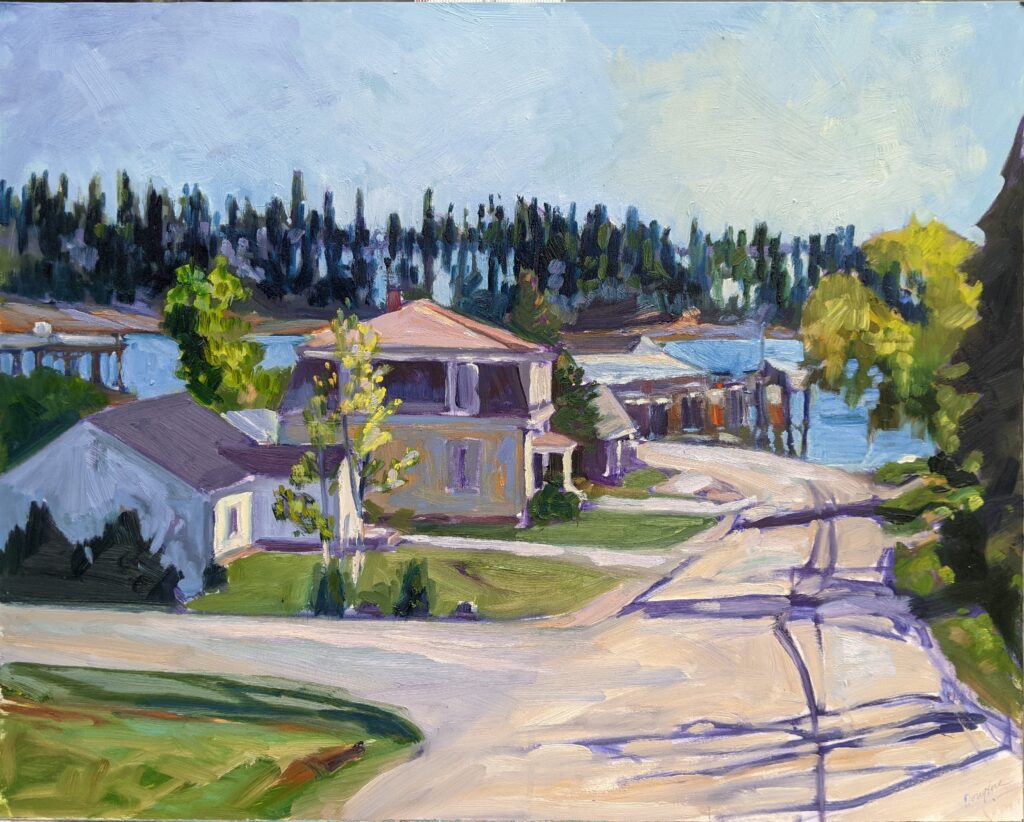

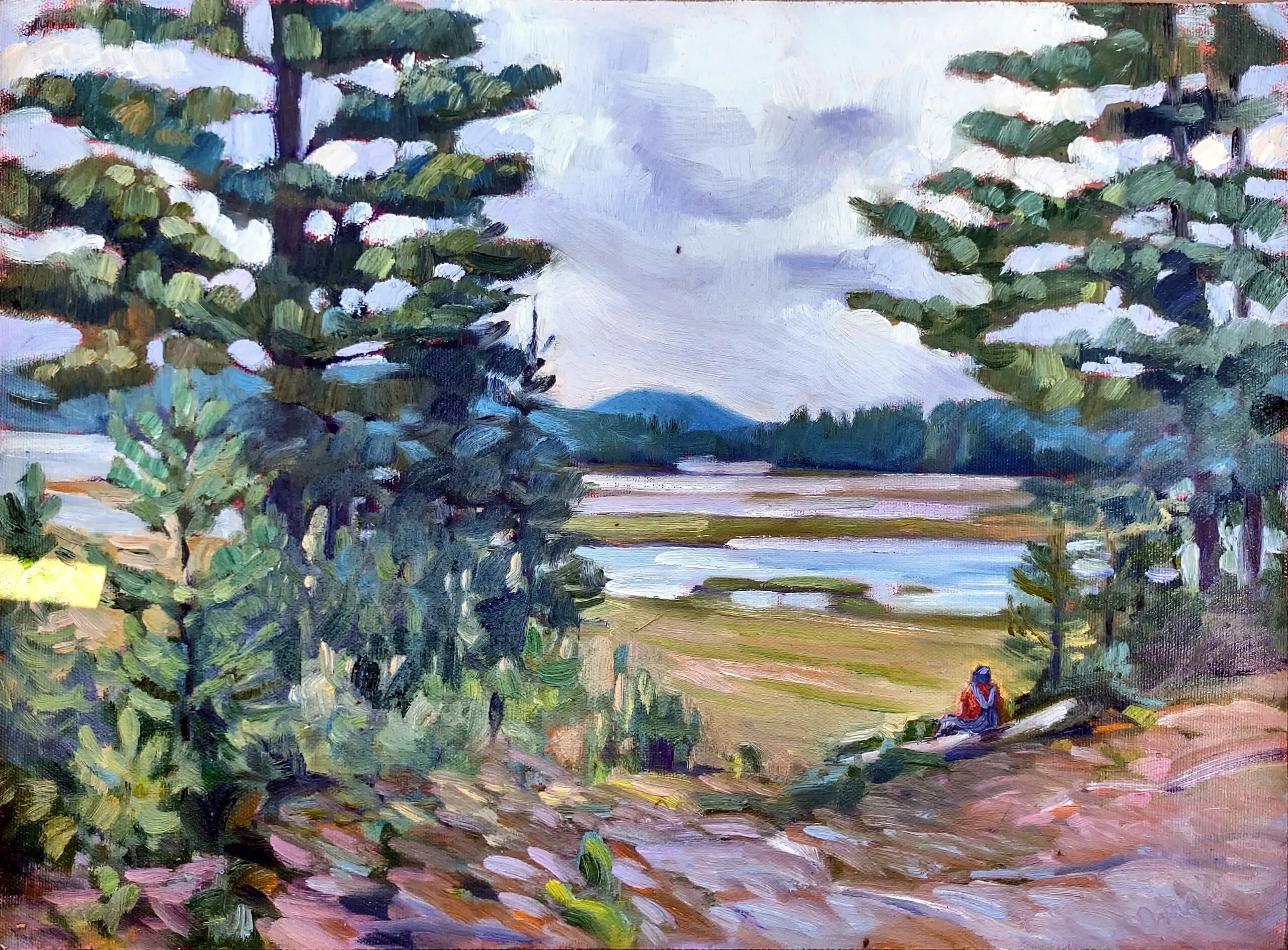

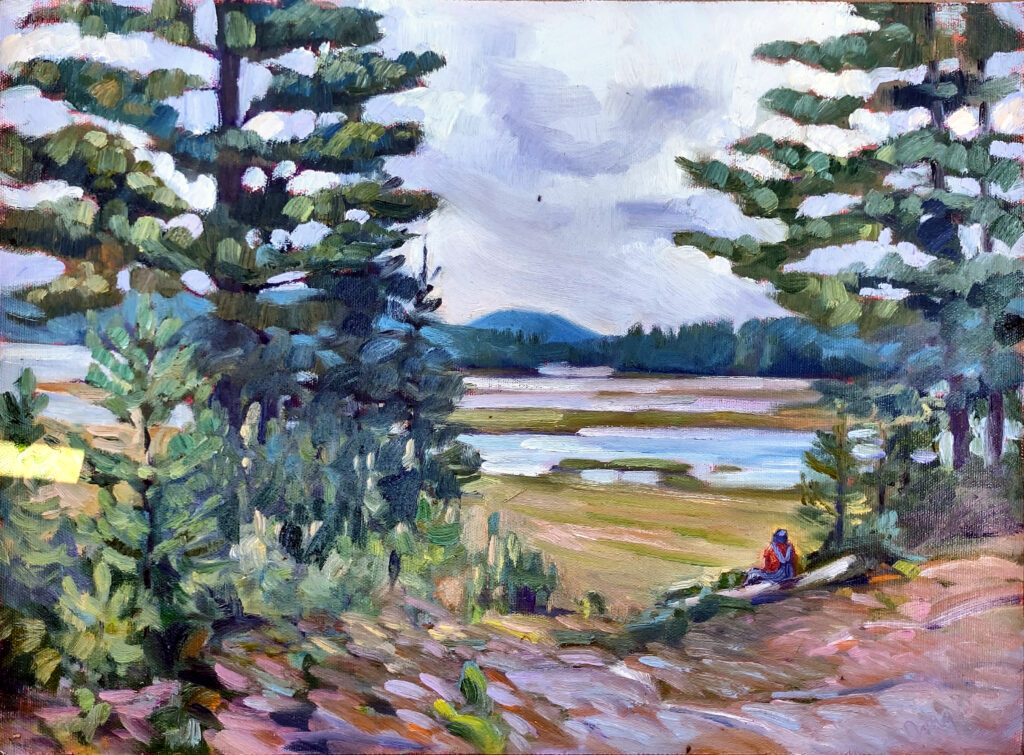

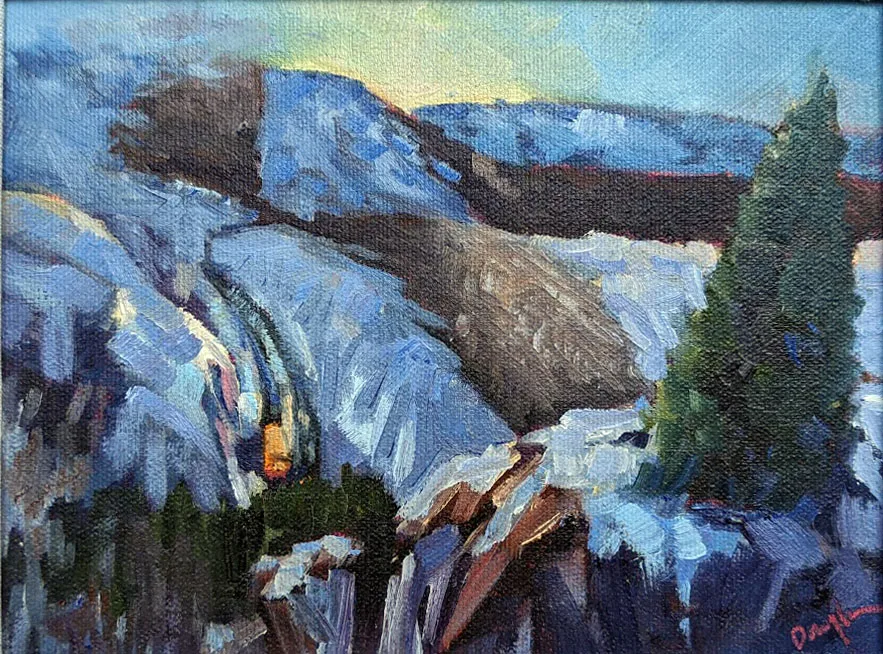

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.